克莱姆森大学主校园餐饮设施

美国南卡罗来纳州克莱姆森市

Sasaki

Sasaki

Over their 150-year history, land-grant universities have played a tremendous and vital role in the development of the United States and the education of its people. Most of these institutions were established as the result of the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862—during a period of considerable national expansion, economic change, and political upheaval. Their initial mission focused on practical liberal education in the mechanical arts, agriculture, and military sciences. As we now move toward the third decade of the 21st century, new ideas and strategies are emerging for a renewed land-grant mission at a time when the country faces another period of economic change and political unrest.

In retrospect, it is easy to appreciate the foresight of the Morrill Act in advancing “nation-building” for a young country. But how has this mission, drafted in a much different time, held up over the years? Important aspects of the Morrill Act remain valid today: accessible education for the general population, and an evidence-based approach for teaching, research, and service. Other aspects, however, such as the focus on local or state level issues have caused some growing pains in an increasingly global economy. Likewise, the locations of many land-grants—which are often situated in rural or semi-rural areas—may limit their connectivity to economic activity and to potential students.

Those invested in the success of the land-grant idea are considering how their missions and campuses can evolve to best support the needs of our times. Our campus planners have had the good fortune to work with, travel to, and study dozens of land grant universities over our firm’s history—including developing master plans for nine institutions over the last decade. This wide-sweeping experience has provided us with insight into the various planning strategies land-grant institutions are implementing to bring about change.

Below, we provide an overview of these strategies which fall into three main categories: embracing changing demographics, building a broader network, and rethinking campus legacies to build solutions for the future.

Land-grants initially focused on agricultural, mechanical, and military arts—critical skills for the fast expansion of the 19th century. Today, these institutions have evolved into major public universities with more diverse student bodies and a much broader teaching, research, and service mission. This is leading to new ways of thinking about inclusion, an increasingly important consideration as Gen Z, the most diverse generation in modern American history, moves through college.

How can the land-grants respond to the changing demographics of the country? Especially those land-grants located in rural areas where diversity is often not reflected in the host community population? Many are serving diverse populations through branch campuses and online programs—making the land-grant proposition more accessible. In nearly all cases, efforts to extend enrollment requires new places and services that are welcoming and inclusive.

On the flagship campuses, new approaches to building community are being developed with the goal of providing “common ground,” or places where all members of the community feel welcomed and are offered access to the full breadth of the land-grant mission.

Much of this common ground constitutes spaces outside of learning environments, such as residence halls and public spaces for gathering. Student centers, academic commons, and other areas that encourage interaction among students and faculty are taking on new importance. These spaces are critical as institutions seek to deliberately assist students in developing the social and soft skills they will need to succeed. While not unique to land-grants, the three major areas where campuses can have impact on a students’ life outside the classroom include where they sleep, eat, and gather—which, spatially, are most often represented by residence halls, dining services, and student and cultural centers.

We have seen a great deal of investment in new ways of organizing residential life around learning communities and other social or academic themes. These new facilities are emerging as many institutions address the limitations and conditions of older residence halls which, in many cases, were designed as dormitories for a predominately male population. These older halls, subsequently, lack the room configurations, support facilities, and social spaces that would be attractive to a diverse range of students.

We have also seen new attention placed on student centers, dining, and academic commons and other places where students come together. Major new residential facilities have been completed in the heart of many land-grant campuses—representing a shift in the importance of residential life in shaping the campus experience. Here, we highlight a few such projects.

Major program reconfigurations often clash with outdated building stock. South Carolina’s Clemson University, for instance, recently invested in the first-year experience with its new Core Campus Housing and Dining complex (Figure 1). The Core Campus replaces a 1950s barracks-like facility which featured a configuration that no longer aligned with expectations of today’s student body. This investment is coupled with a new core campus dining hall designed to not only meet functional dining needs, but also to serve as a social hub for the residents and the broader campus community. The complex also includes housing and program spaces for the honors college which, again, creates an environment that is more inclusive of a wider range of students.

Figure 1: Clemson University’s Core Campus creates a new social hub at the heart of campus

Virginia Tech (VT) is planning new housing to accommodate growth and to provide a wider range of housing types responsive to the learning communities and other themes being introduced into the campus environment. This includes a new living-learning residential facility in the heart of the proposed Creativity and Innovation District, an area of campus where the creative and visual arts, architecture, engineering and business are envisioned to come together with the university’s business and local partners. Other planned housing includes a residential complex associated with the College of Business. This proposed facility will be designed to engage students in global business issues and opportunities and will feature visiting international faculty-in-residence.

Since 2012, The University of Kentucky (UK) has developed almost 7,000 beds of housing on prime campus land through a major public-private partnership (P3). This new housing stock expands the conception of residential life for the campus, creating 19 new learning communities—each with a particular academic focus. The learning communities include academic offices, active learning spaces, and group and individual study rooms featuring technology-enabled environments, food service, and recreation areas (Figure 2).

This pace of development has transformed the campus experience in record-time, while enabling the university to focus on other much needed investment including a new science center, an expansion to the business school and a new campus center. UK has also completed a 1,000-seat dining and student engagement facility through another P3 arrangement, which now functions as a secondary campus center.

Figure 2: The University of Kentucky has leveraged P3s to transform the student experience

Investments in campus centers are also an emerging focus at many land-grants. In years’ past, there was some discussion about the relevance of campus centers in an age where students are more mobile and they interact with their peers virtually. It now seems that there is an increased interest in providing places where people can come “to see and be seen,” and to meet people in vibrant environments that facilitate social engagement and informal study. Student centers seem particularly important for engaging students during the academic day, especially those that commute and therefore have no specific “home base” on campus. These spaces serve the practical needs for food and services, the desire for social interaction, and encourage more interaction among and between different student groups.

These services and experiences are not confined to student centers. On many campuses, libraries serve this function. At the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, for example, a library renovation proposed as part of the master plan has created a new type of student engagement and collaboration hub focused on academics. In this case, a library space positioned along a major pedestrian route has been transformed by removing a dusty collection of government documents and opening up the building to create a vibrant academic and learning commons.

The population of Virginia Tech, like many land-grants, has transitioned over time, becoming co-ed decades ago, and increasingly coming to represent the rich cultural diversity of the nation. Today, as VT plans for its next 30 years, renewed emphasis is being placed on the student experience. This includes all sectors of the student population—from those living on campus, to those that walk, bike, and take transit to campus on a daily basis. Planned changes include integrating the transit network more deliberately and seamlessly with the academic environments, student services, and amenities of the campus.

A central driver of these changes is reimagining the historic layout of the campus. As designed, VT’s campus emphasizes military discipline—still evident today in the orderly beauty of the campus. This formal structure, however, means that some areas of the campus lack the amenity and support services needed to serve the current student population. To that end, the master plan provides strategies for creating a network of distributed commons in response to the scale of the campus and the distribution of the population. These centers are linked by means of a proposed pedestrian and circulation loop around the campus which will serve to address mobility and accessibility challenges associated with the topography of the campus.

A key recommendation of the VT master plan involves the repurposing of a centrally located building in the academic core to create the Central Campus Commons—the “common ground” to engage the daytime campus population. No such space exists today and is essential to providing amenities and services to all campus users including the commuting population that will access campus via an adjacent multi-modal transit facility proposed in partnership with the town of Blacksburg, VA. The Central Campus Commons will include meeting, dining and gathering spaces around a reimagined plaza at the heart of the academic core.

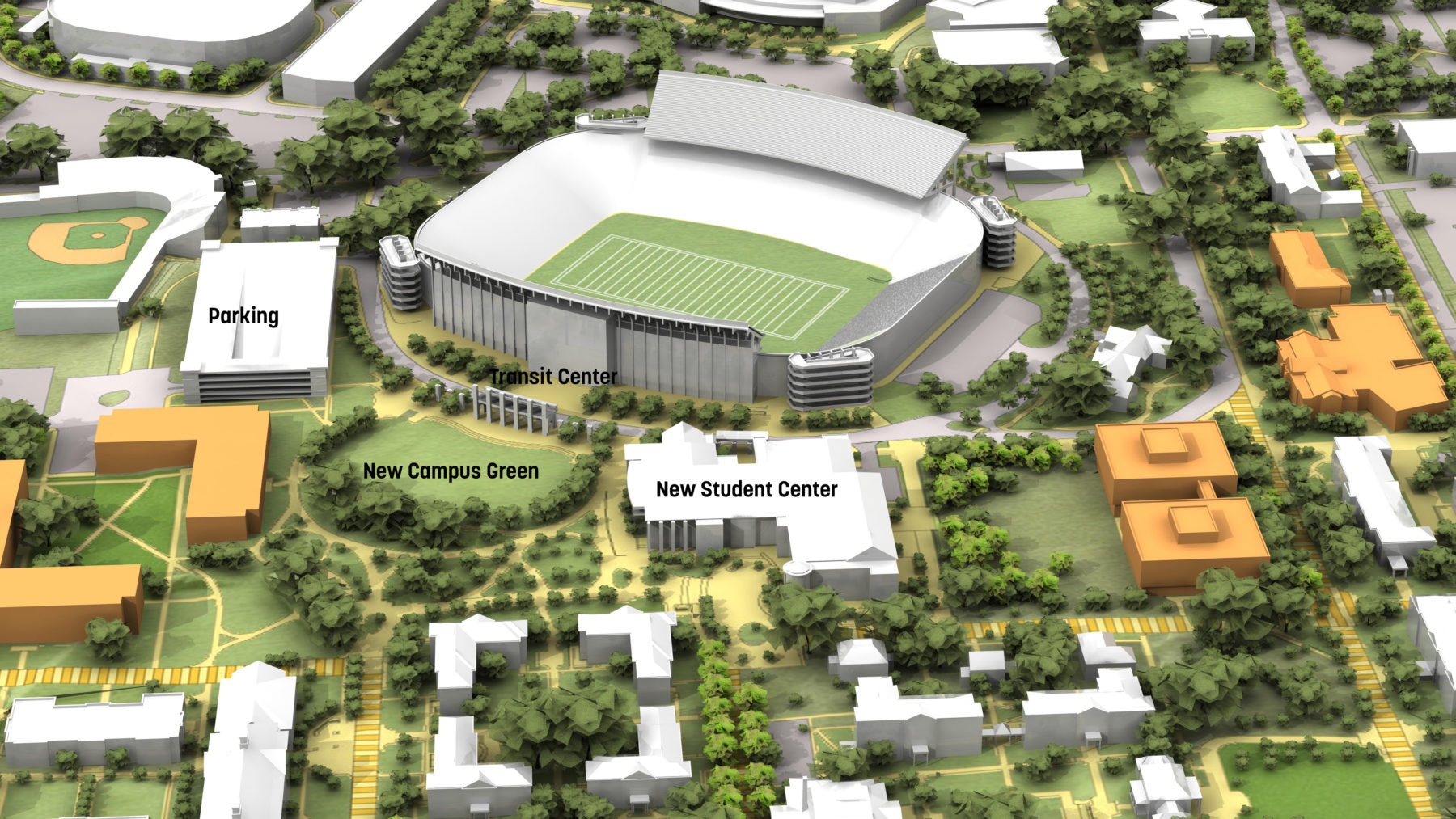

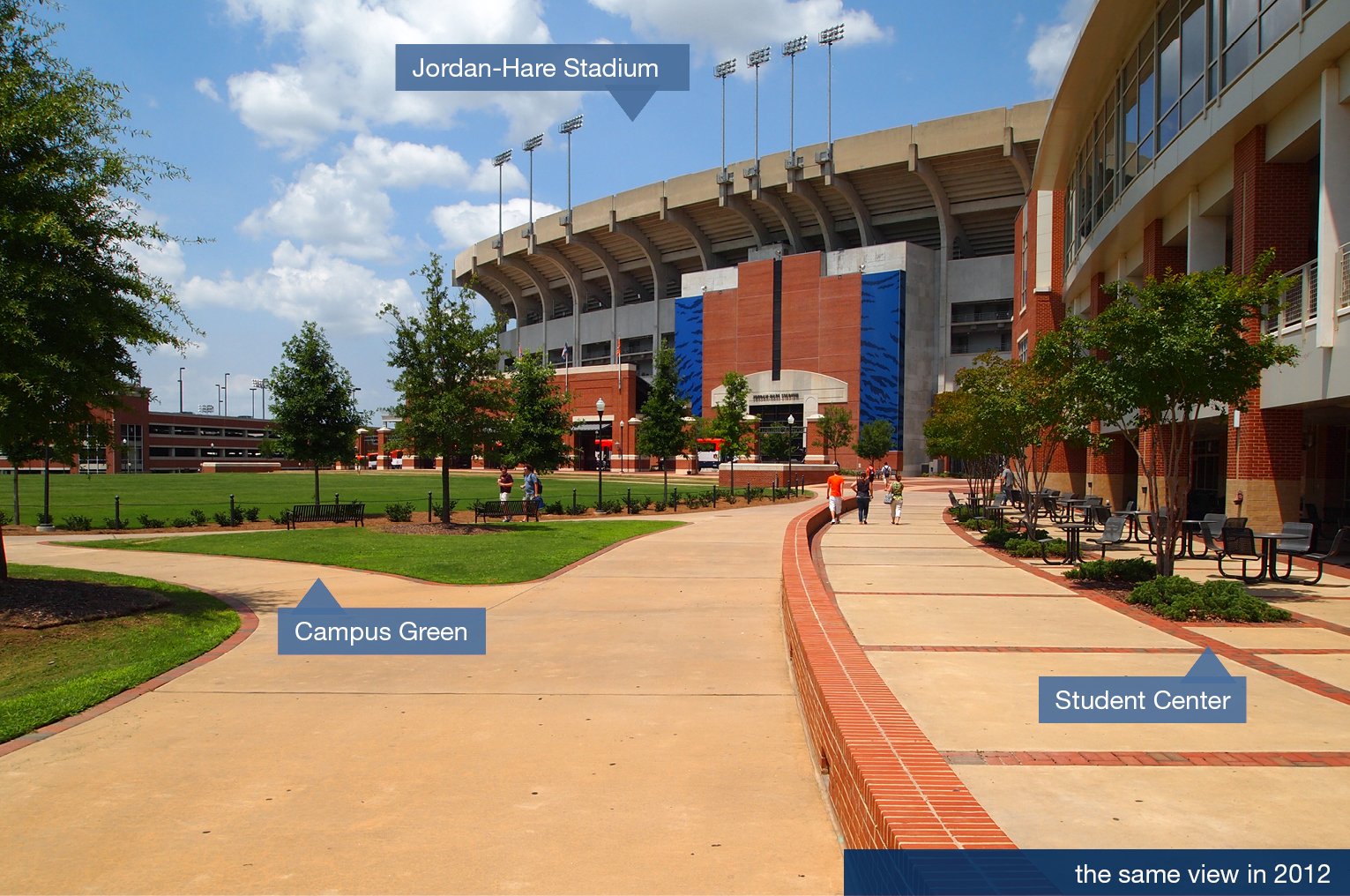

Prior to the construction of the Campus Green and Student Center, Auburn had well-proportioned quadrangles and other positive open spaces, but lacked that one defining and memorable space—the “heart”—found on many other land-grant campuses, such as the Drillfields at Virginia Tech and Mississippi State; Bowman Field at Clemson; and the Mall at the University of Maine.

Figure 3: Auburn University’s Campus Green & Student Center create a central gathering place

Figure 4: Auburn’s new transit center creates a welcoming feel for commuters

The Campus Green and Student Center is integrated with a transit center to better serve the commuting population. The outcome is a new facility that functions as the “grand central station” of the campus, providing amenities and conveniences for commuters. (Figure 3) Each day, transit riders pass through the Student Center, creating a daytime hub for all members of campus community. This deliberate arrangement of the transit and student center also delivers the users directly to the facility, making it a vibrant social center and contributing to the success of the dining, retail, and services located in the building (Figure 4).

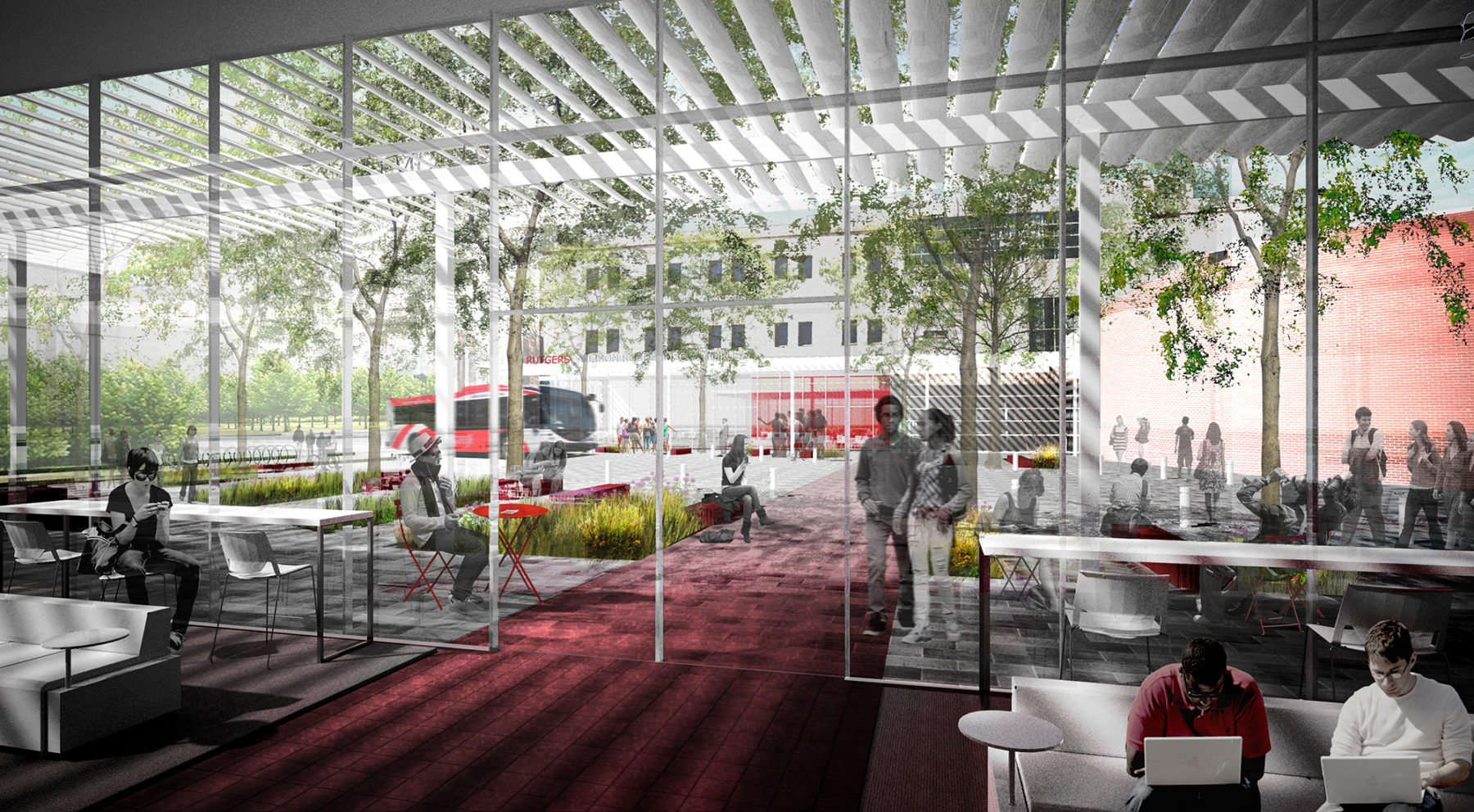

The flagship campus of New Jersey’s Rutgers University’s is actually the amalgamation of several campuses. Over the course of a few decades, these campuses have been developed to strengthen the breadth of the University’s offerings, resulting in a large geographic footprint spanning the communities of New Brunswick and Piscataway. This footprint creates a challenging experience for students, who rely on intra-campus transit to move from class to class.

The master plan proposes new transit hubs on each of the five campuses that collectively define Rutgers New Brunswick–Piscataway. These hubs, in many cases, coincide with both existing as well as proposed campus centers with the intent of enhancing the student experience and responding to the distributed nature of the campus population that results from the considerable physical separation between the campuses and the functional need to provide transit connections (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Proposed transit hubs at Rutgers are intended to improve the intra-campus travel experience

As a re-affirmation of the basic land-grant ethos of providing education for all, many institutions are finding new ways to welcome a diverse range of voices to the table. Through celebrating diversity of perspective and knowledge, these institutions are broadening the educational experience and the overall quality of education.

What does this look like from a program and facilities standpoint? While many land-grants have created cultural and inclusion centers over the years, usually within existing student centers, some are investing in new facilities. Common program uses for these centers include student support services, weekly or monthly meetings, as well as workshops and cultural events. No matter the shape, size, or location, dedicated centers for student group expression play a crucial role in reinforcing commitments to inclusivity.

We recently had the opportunity to tour Oregon State University’s campus, and observed a series of cultural centers distributed across the campus. These seven centers have the expressed goal of engaging traditionally underrepresented populations, with each offering a unique architectural identity and location on the campus. The centers reinforce Oregon State’s commitment to social justice, diversity, and inclusion and provide environments where students can share experiences among peers as well as others interested in learning more about their culture and heritage.

Economic prosperity in the U.S. depends on a deepening understanding of the global context. The land-grant of today must look beyond its home state, to take its expertise to the larger world while also bringing the world back to the population it serves. It is also critical to widen access to education as the nation diversifies to include students from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds (urban, suburban and rural). There is much work to be done on the state and national scale to soften the divide between urban and rural opinions on economic, political, and cultural matters. Tackling these challenges requires partnerships with other institutions, organizations, and businesses to ensure that students are exposed to differing cultural, political, and economic ideas. Given the diversity of their student bodies, the land-grants are well positioned to respond to these challenges.

Increasingly, the nature of the problems and issues addressed by land-grant missions go beyond the boundaries of the states to address regional, national, and international issues. This is a critical evolution, but one that can at times place the institutions at odds with state governments and citizens who seek a focus on the state. Balancing this is important for land-grants. They must engage with the nation and the world to solve problems that go beyond their state boundaries but do so in a way that is relevant to the state government and citizens they serve. Re-imagining pedagogical structures can organize coursework around major global challenges. Intentionally disrupting traditional departmental divides can create hubs for cross-disciplinary problem-solving.

Land-grants are also well positioned to help bridge the cultural divide between the urban coastal cities and rural areas of the heartlands. Their unique mission, range of programs, and diverse socio-economic student body enables them to bring together members of the population that may otherwise never meet. Even in their home states, they bring together urban, suburban, small town, rural and international students in meaningful ways that can facilitate engagement, interaction, and expanded understanding.

Given that many land-grant campuses are located in rural and sometimes isolated regions, several have established satellite campuses in urban areas enabling them to address new population groups and respond to the “grand challenges” of today. These challenges tend to be more urban in nature and often require partnerships with other institutions, businesses, and government organizations located in urban areas. Land-grants located in major cities such as the University of Minnesota and The Ohio State University, among others, have an advantage in this regard. Proximity to a larger and more diverse population offers increased opportunities for economic partnerships and research—while land-grants in more remote areas must deliberately “reach out” to establish such connections.

In response, some institutions are looking beyond their flagship campuses to form unique partnerships, conduct new types of research, and provide new services to the citizens of their state. This is particularly true for institutions located outside major population hubs and capital cities. The much-publicized Cornell Tech campus in New York City is perhaps the best-known example of this approach, but there are several other institutions who are successfully developing similar campuses.

Clemson University, for example, developed the International Center for Automotive Research (ICAR) in Greenville, South Carolina, some 40 miles from its flagship campus. Located at the midpoint between Charlotte and Atlanta on the Interstate 85 corridor, ICAR is an automotive and motorsport research campus designed to provide an innovative and collaborative environment. Today, 21 industry partners, including BMW, are located on the ICAR campus to conduct research and train engineers.

Likewise, Virginia Tech is exploring new ways of organizing research and academic activities around Destination Areas or “grand challenges” that the University is best positioned to lead. These include: 1) Adaptive Brain and Behavior; 2) Data and Decisions; 3) Global Systems Science; 4) Integrated Security; and, 5) Intelligent Infrastructure for Human-Centered Communities.

Virginia Tech is aligning the grand challenges of its strategic plan with the physical master plans for existing and potential locations across the Commonwealth of Virginia. In Roanoke, where the VT Carilion College of Medicine is located, emphasis is being placed on the Adaptive Brain and Behavior challenge. In the National Capital Region (Washington D.C. area), activities are focused on Data and Decisions, and Integrated Security—capitalizing on the proximity to national agencies and organizations (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Virginia Tech is expanding its reach through a series of strategic extension campuses

Proximity to the national government and the associated organizations, institutions and businesses presents unique opportunities for the University to align its teaching research and service capabilities with the needs of the state and nation. It also enables VT to take an international viewpoint given the status of Washington D.C. as a global capital city. Perhaps VT’s most ambitious endeavor is about to get underway. A new Innovation Campus was announced in November 2018 with the goal of delivering computer science graduates and research capacity in response to Amazon’s new headquarters in Crystal City, Virginia, just outside the District of Columbia.

VT’s other Destinations Areas will be primarily based in Blacksburg, home to the main campus, where potential initiatives include an “Intelligent Infrastructure Corridor,” which is envisioned to feature web-enabled sensor technologies and autonomous vehicle testing. In the proposed Creativity and Innovation District of the campus, the goal is to bring together architecture, art, business and engineering programs to partner with business and industry on problems that require integrated “design thinking.”

Land-grants have long provided community outreach services via agricultural extension centers and stations, delivering value to the agricultural and farming communities in their host states. Historically, such outreach led to great strides in crop yield, and animal and human health. Today, these services remain valuable and are likely to be increasingly important as the agricultural sector addresses contemporary problems associated with climate change.

Given their long histories and various phases of development and government investment, new emphasis needs to be placed on deferred maintenance at land-grant institutions. This is particularly important for the sciences as well as agricultural and extension service facilities, key programs of the land grant tradition. A renewed focus is needed for modernizing and investing in facilities and programs relevant to the 21st century.

An October 2015 Sightlines study, supported by the Board on Agriculture Assembly of the Association of Pubic and Land-grant Universities (APLU), found that the deferred maintenance for agricultural facilities at 27 land grants and other institutions contributing data to the study totaled $8.4 billion or about $95/gross square footage.[i] Of this total, $6.7 billion of the deferred maintenance is associated with buildings older than 25 years.

Of particular concern are science research facilities and classroom and teaching spaces, of which 60% and 64% of spaces are over 25 years old, respectively. Sightlines determined that of the $8.4 billion total, $3.2 billion is associated with science research facilities and $2 billion with classroom and teaching facilities. What this means in simple language is that many land-grant institutions are conducting 21st century research and teaching in buildings dating from the 1950s to the 1970s, many of which are expected to reach critical condition unless funding and renovation strategies are developed.

In support of these fast-evolving programs, several land-grants have developed investment strategies in response to deferred maintenance issues. New facilities to support agriculture and plant sciences are underway at NC State and Washington State University. Similarly, at the University of Nebraska, initiatives are underway to focus their teaching, research, and outreach activities on food, energy, and water—directly confronting some of the looming challenges that face the agriculture industry in the Midwest and western states of the US, as well as the world beyond.

Land use also is a concern for agricultural and veterinary medicine programs—land that is critical for the research mission and operational needs. Land adjacent to core campuses is highly valued for its accessibility and proximity to the faculty, staff, and student populations. Convenient access is critical for the logistics of educational, research, and operational activities. The protection and continued use of land resources also is critical for engaging students in field observations and research as part of their educational experience. If agricultural land is remotely located, scheduling and transportation become major considerations.

Over the years, various planning strategies have emerged for protecting agricultural land resources for ongoing and future uses. At Auburn University, the master plan includes a land use code, guidelines and policies for managing campus land resources. Internal management procedures ensure that the value of the land is acknowledged and protected.

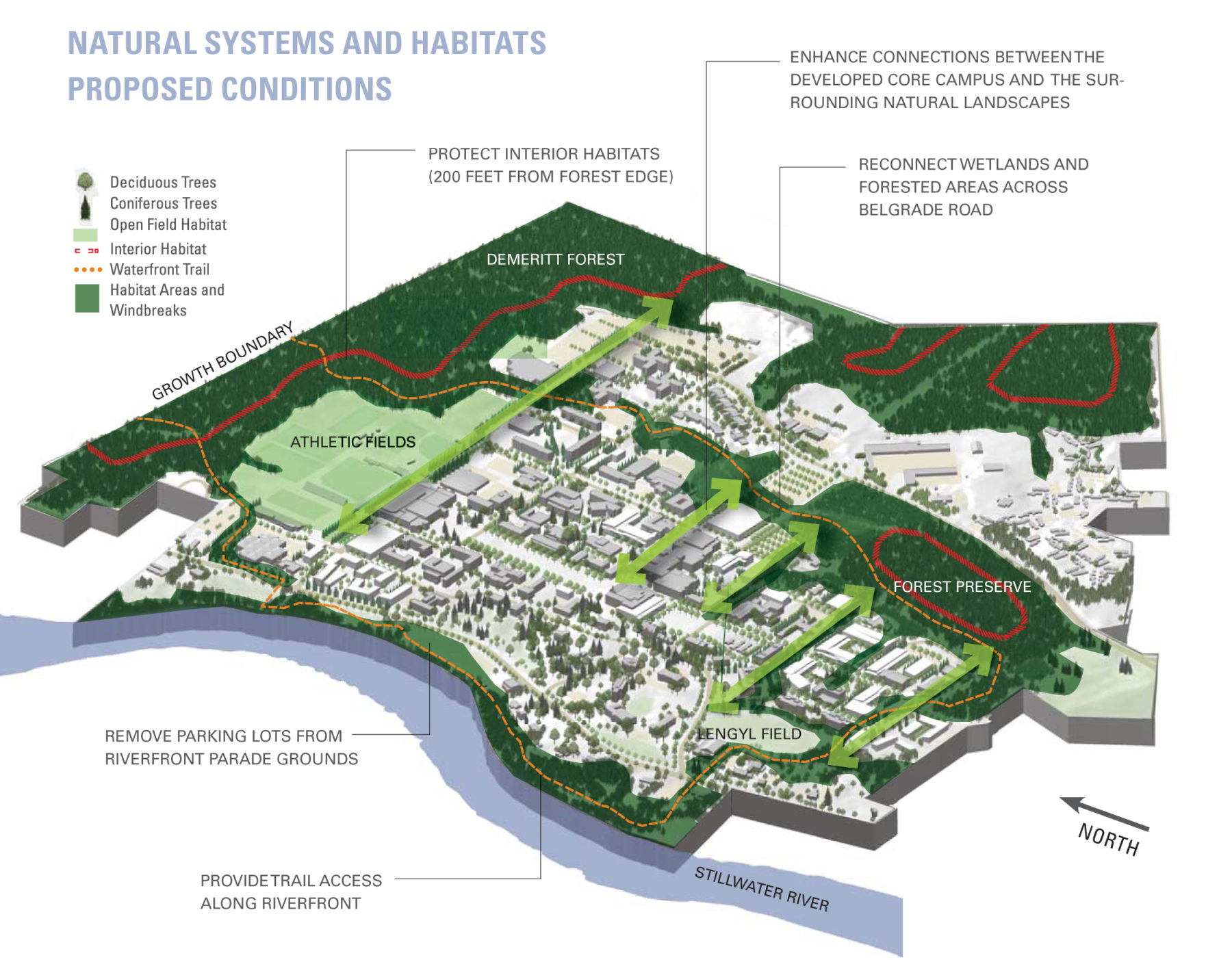

Similarly, several master plans have included a growth boundary to protect land associated with the agriculture, forestry, veterinary medicine and other mission-related activities. At the University of Maine, a growth boundary is intended to protect forested land and combat incremental erosion of the resource (Figure 7). At Mississippi State, a growth boundary protects farmland in floodplain areas as well as land placed under pressure from adjacent residential development and potential commercial development.

Figure 7: The University of Maine includes a growth boundary to protect campus forested areas and wetlands

At Virginia Tech, the growth boundary outlined in the master plan protects land for agricultural and veterinary medicine educational and research activities; reserves land for key operational activities such as hay production and nutrient management; and, protects the rural character and image of the campus—an important aspect of the institution’s land-grant heritage (Figure 8).

Figure 8: VT’s Agriculture Belt advances research while celebrating the university’s heritage

The planning and protection of agricultural land at Virginia Tech also extends beyond the main campus proper to include the university’s network of Agricultural Research and Experiment Centers (ARECs). As an outcome of the planning process, information and data on the ARECs are now recorded in a GIS and web-enabled program. This tool is intended to facilitate the management of the land resources and, in the process, help others see the potential value of the land for other purposes such as state-wide data collection, accessibility to major population centers or to geographically-specific problems that would benefit from university engagement.

Traditionally, planning considerations for agricultural land-use focused on the quality of the land, as determined by its topography, underlying soil conditions, and proximity to campus. Over time, these agricultural lands have come under pressure from adjacent land owners and communities, especially those surrounded by suburban development.

The University of Minnesota and the University of Nebraska face such concerns. Decades ago, both institutions located agricultural lands on farmland outside their main campuses. Nebraska’s East Campus, situated approximately three miles from the City Campus, has over the years, come to be surrounded by suburban development. The University of Minnesota’s St. Paul campus offers prime soil conditions for the agricultural research, but is now split by an arterial road and surrounded by development—a hardly conceived-of scenario when the land was initially purchased. Bottom line is that these agricultural lands are essential and will be even more important for the mission moving forward. The protection and stewardship of agricultural, therefore, is critical for the future of the land-grant mission.

The Morrill Act of 1862, named for the bill’s sponsor, Vermont Senator Justin Smith Morrill, and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, placed a clear priority on educating the common citizen and advancing the practical skills necessary for prosperity. Those two aspects: accessible education for all, and a focus on the practical skills, are still highly-relevant to the mission of the 76 land-grant institutions in the United States.

In a speech years after the passage of the act, Senator Morrill expanded on the broad-reaching intent of the act:

The land-grant colleges were founded on the idea that a higher and broader education should be placed in every State within the reach of those… who may have the courage to choose industrial locations where the wealth of nations is produced; where advanced civilization unfolds its comforts, and where a much larger number of the people need wider educational advantages, and impatiently await their possession.[ii]

True to his words, these institutions have evolved right along with the nation, offering education to a wider and wider population of eager students. Increasingly, that mission has steered land-grants to attract students from diverse racial, cultural, and socio-economic backgrounds to better reflect the country’s increasingly rich store of varied experiences. Campus facilities and programs must accordingly adjust to reflect modern-day student populations and functional needs—which, for many land-grants, has led to an honest assessment of residential life, dining, and spaces for student gathering. Living/learning residence halls offer a new pedagogical approach—investing in the thought that “learning” occurs outside of the traditional classroom. Campus centers offer student groups places for gathering, honest discourse, and exposure to ideas they would have never otherwise encountered.

The original 1862 Morrill Act outlines the mission of land-grants as follows: “to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts… in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.”[iii] Though agricultural and mechanical arts may have changed a bit since the 1800s, they are still key drivers of our national economy—and arguably more relevant than ever. Innovations in agriculture will be necessary to ensure food security in the face of climate change, both on a domestic and international scale. Declines in a mechanically-minded and educated workforce are oft-repeated complaints from business-owners, with a 2018 Deloitte report placing the gap between openings and qualified applicants over the next decade at a staggering 2.4 million.[iv] Who better to help our nation remain on the cutting edge than the institutions created to offer education in precisely these fields?

Moreover, the country’s land-grant universities are developing programs that offer their students experience in newer drivers of today’s economy. Virginia Tech’s pedagogical structure, focused on “grand challenges,” leverages connections to government and other partners to offer real-world and relevant experience to students that will prepare them for the workforce. Clemson’s ICAR campus strengthens the connection between automotive industry partners, and creates a pipeline for talent.

As land-grant institutions chart the course for their campuses in the years ahead, there are several lessons to be learned from ongoing planning in the first two decades of the 21st Century.

In closing, we have great hope for a renewed land-grant mission in the United States—one that respects the origins and maintains a focus on rural America while also engaging suburban, urban and international constituencies in ways that are beneficial for nation-building in the 21st Century. We also see great need for integrated planning and innovative strategies for renewing our land-grant campuses for another century of service to communities, states, the nation and the world.