Small Cities, Big Impact

Sasaki

Sasaki

Across the United States, small towns and cities are advocating for critical quality of life improvements to realize the full potential of their open spaces and streets. From the Ohio River Valley to the Florida Keys, we’re working with municipalities to help them reimagine their urban environments for the 21st century and beyond.

Located at the juncture of Illinois, Kentucky, and Indiana along a horseshoe-shaped bend of the Ohio River, Evansville has long been a place of meeting and movement. The land was once home to a thriving Mississippian culture community, with evidence of settlements dating back to around 1100 to 1450 CE. Later, groups of Shawnee, Miami, and other tribes moved into the area around 1650, with Shawnee still living on the banks of Pigeon Creek near Evansville when European settlers arrived. Its strategic position contributed to its manufacturing boom throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the scenic riverfront was central to the social and cultural life of the city’s inhabitants.

Yet despite its nickname, the River City’s connection to its waterfront has never reached its full potential as the region’s greatest asset. A busy four-lane road has inhibited pedestrian access to the riverfront, and the nearby towns of Mount Vernon and Newburgh have similarly faced challenges with car-centric infrastructure and underutilized spaces occupying important waterfront areas. The industrial decline in the Midwest has challenged places like Evansville, where the population has been steadily decreasing. At the same time, rising costs in large metropolitan centers are prompting some to seek more affordable cities.

Local leaders here believe in the strength and vibrancy of the city and its natural resources. Re-connecting the community with the forgotten waterfront, they’ve recognized, will be key to bringing out the best in Evansville and building resilience in this anchor city.

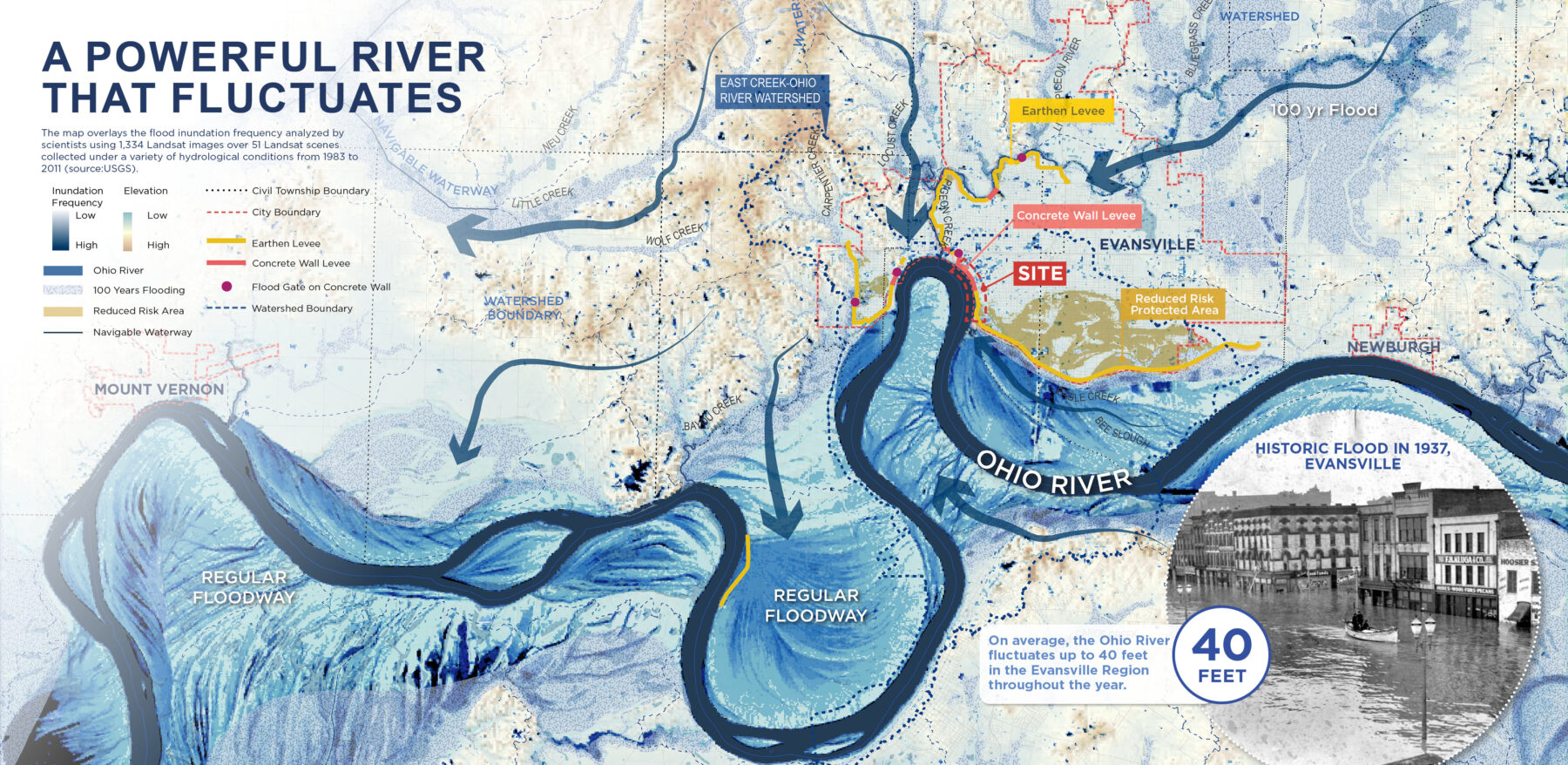

Learning from the past is key to planning for risk mitigation strategies along the Ohio River.

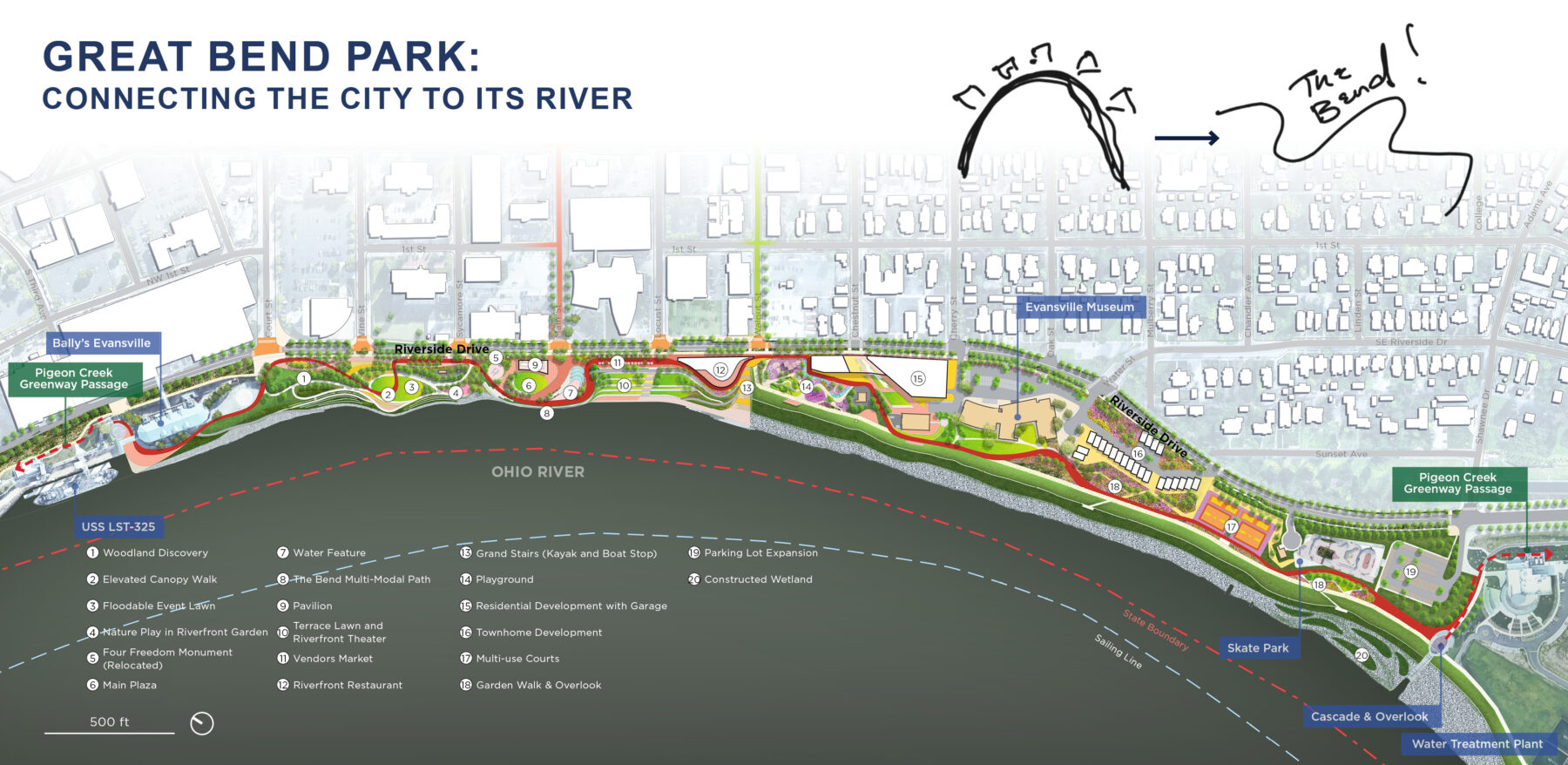

Sasaki’s Ohio River Vision and Strategic Plan tackles a 50-mile stretch of water that flows through downtown Evansville and spans four counties. The centerpiece of the plan is Great Bend Park, a new destination for recreation and entertainment that grew out of extended exchanges with community members.

The team took a bold yet simple approach to the new Great Bend Park: Bring the River to the City and the City to the River. By “bending” the experiences the new park embraces the Ohio River. Working with the Army Corp and Levee Authority, the new plan strategically relocates the levee in two key locations and integrates into the park throughout the rest of the one-mile-long riverfront. Elevation shifts at critical points in the park will help create vistas and differentiate recreational and commercial spaces, all the while functioning as flood mitigation infrastructure.

Great Bend Park stretches along the riverfront, inviting Evansville residents to connect with their natural landscapes.

The Plan also advocates for more robust regional collaboration along the Ohio River. In the nearby communities of Newburgh and Mount Vernon, we’re working with residents at smaller, targeted scales to stimulate growth and connections across the Evansville metropolitan area. Both are working to build out trail systems and upgraded parks of their own that celebrate their connections to the shared riverfront.

In Mount Vernon, where the population runs just over 6,000, residents have been vocal and energetic about their visions for their 5-acre riverfront park upgrade. One in 16 residents participated in the first community outreach–a turnout we almost never see in large municipalities!

A new grand terrace features dining and recreational boating facilities.

The “Bend,” a winding multi-modal path that runs the length of the park, adds dynamism to the landscape and invites people to engage with the waterfront, while doubling as flood mitigation infrastructure.

The waterfront is also at the core of Sasaki’s plan for making Lake Monona a more accessible and resilient public resource for Madison, Wisconsin’s capital city. Working with Madison residents and members of the Ho-Chunk Nation, the original inhabitants of the area, Sasaki conducted a public engagement process that yielded over 2,400 survey responses.

The park will span a 1.7-mile stretch of the shoreline and play host to new amenities like an amphitheater and community boathouse.

What became clear was the need to cultivate connections between people and the shoreline. Some of the key proposals that emerged from these dialogues included creating accessible green spaces with safe pedestrian and biking infrastructure, uplifting the narratives of Native peoples and the sacred significance of the Lake, and building a living edge to support the growth of local flora and fauna.

Slated to break ground in early 2026, the 17-acre linear waterfront park will be a new oasis for Madison, drawing upon the histories embedded in the land to shape a future for the lakefront that celebrates the cultural and ecological life of the area.

The protected shoreline will help nurture local wildlife and create opportunities for environmental education.

The park caps over John Nolen Drive, melding into the fabric of the city while creating more green spaces amidst the existing infrastructure.

In Mallory Square, the heart of Key West’s historic waterfront district, we’re working with residents to revitalize a destination important to locals and visitors alike. Every evening, the Sunset Celebration brings the plaza to life as artists, vendors, and performers gather against the glowing backdrop of the Gulf. Yet the lack of shade, seating, and public restrooms, and predominance of dark paved surfaces have made the plaza hot and unwelcoming during the day. The area’s vulnerability to extreme weather conditions and flooding have also brought urgency to resilience-building projects across the Keys–particularly in areas with deep cultural and communal significance like Mallory Square.

Increased tree shading and seating will help make Mallory Square a more inviting and comfortable environment at all times of day.

Expanded pedestrian pathways highlight the sunset vistas and bring people closer to the water.

Our plan will maximize the full potential of the underutilized plaza by building robust shade systems that include new tree plantings and shade canopies, improving pedestrian access to waterfront and its beautiful views, and adding seat walls and steps to mitigate flooding risk. These physical upgrades and strengthened connections to surrounding waterfronts and streets will highlight Key West’s maritime heritage by better integrating the island’s historic buildings into the experience of Mallory Square. By activating these spaces so they can be used at all times of day, the master plan will reconnect city and sea, celebrating all that makes Key West one-of-a-kind.

Places like Dublin, Ohio, located 17 miles northwest of Columbus, are also using water systems as a guiding force to revitalize employment and innovation centers in exurban towns and cities.

Currently, older office parks throughout the city privilege car-centric transportation over pedestrians, and surface parking lots occupy swaths of valuable land. This renders much of the landscape impervious and hinders the growth of local ecosystems that might otherwise thrive in the city’s several stormwater ponds as well as decreasing overall land values. These older office parks lack employee amenities and multi-modal transportation options, and continue to be plagued by high vacancy rates in the post-pandemic era.

Weather-adaptable amenities will animate the district all year-round, providing diverse opportunities for recreation and commercial activity.

Public spaces will be integrated into housing and commercial spaces, encouraging pedestrian flow.

By reconfiguring stormwater ponds to create a continuous waterway to improve stormwater management, and consolidating parking and underused buildings, Sasaki is freeing up space for Dublin to transform Metro Center, one of the city’s first office districts, into a vibrant mixed-use destination–no longer an asphalt expanse, but a rich, mixed-use environment that animates the district beyond the typical work day hours.

The confluence of small yet vital changes, shaped by the needs and desires of local residents, give rise to visionary plans that can transform the futures of these towns and cities and serve as models for other locales.

The energy that each community brings to the table has been essential to keeping momentum going. All have been steadfast in pursuing civic and federal funding opportunities, research and development grants, and other sources of capital investment in order to realize these multifaceted visions. Engagement meetings are lively and well-attended, and residents have voiced clear commitments to making their homes better, stronger, and healthier. This buy-in isn’t just helping shape the course of planning–it’s critical to helping us understand what makes these places special to the people who inhabit them, and how we can nurture and share these landscapes for generations to come.