Meet the Framework Plan: A Flexible Master Planning Approach

As context and constraints evolve in a university setting, it’s important to have a structural understanding of how decisions will be made

Sasaki

Sasaki

“We are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist, using technologies that haven’t been invented, in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet.”

The following piece, written by Sasaki Principal Dennis Pieprz, Honorary ASLA, and Senior Associate Romil Sheth, originally appeared in SCUP’s Planning for Higher Education journal, 45 (2), January-March 2017.

These words belong to Karl Fisch, an American K12 teacher who made a big splash with “Did You Know?” a 2006 video analyzing the impacts of globalization on education. Last year, directors from the Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey shared this quote with us in a kick-off meeting for the Tec 21 Educational Model—a brand new mix of pedagogy and spatial planning that will cultivate well-rounded students ready for today’s challenges. The impetus for this new approach grew from the administration’s concern that their curricula was no longer adequately preparing students for life after graduation. Judging by the growing dialogue reappraising the value of the traditional bachelors’ degree in recent years, it seems they are not alone in their concerns.

It’s not hard to see why this dialogue has been so active. Increasingly, the rate at which new products and processes shake up the market is quickly outpacing the ability of educators to prepare students for the professional world. The integration of technology has become so complete that everybody entering the job market—doctors, accountants, engineers, educators, you name it—need at least basic working knowledge of how the latest hardware and software platforms are impacting and redefining workflows. The expectation of immediate service and the need to work in collaborative teams has ramped up, while barriers to international business have continued to shrink—evolutions that demand employees to be increasingly nimble, responsive, and globally connected. It’s left many asking that if the world is changing so rapidly, how can schools respond? How can they keep up?

The challenge is steep—it’s not just about training students to be ready for jobs in the 21st century, it’s about nurturing a new kind of student. Schools now need to focus on teaching their students how to learn—and how to respond to continually changing times. It’s not about training them to excel for a specific career or industry in the 21st century, but training them to excel in 21st century economies and cultures, of which the most central and predictable component is change—dramatic and rapid change. Additionally, there is growing evidence that millennials are not only concerned with making a decent living, but truly improving the world they live in and connecting with peers.[1] The teaching methods and educational environments of many schools today are not fine-tuned to meet these societal shifts.

Realizing the need to revolutionize their approach to instruction, the Instituto Tec took Fisch’s words to heart as they set out to develop a new pedagogy and campus environments for their 29 campuses across Mexico. They are joining a growing group of innovators in higher education. Many institutions are embracing the uncertainty of these “not yets” as an opportunity to create pedagogical models that shake up the basic experiences of student, faculty, and campus. In times of uncertainty, these schools are not waiting for direction; they’re forging their own.

Admittedly, these claims about the future economies might sound like fear-mongering or prognosticating—except this future is already here. Take Google for instance. It shouldn’t be surprising that a major business disrupter such as Google approaches hiring in a non-traditional fashion. It turns out that they assess recently graduated applicants much differently than the schools they’ve just earned degrees from. Laszlo Bock, Google’s Senior Vice President of People Operations, gave us all an insight into the tech giant’s hiring process in the 2013 New York Times article, “In Head-Hunting, Big Data May Not Be Such a Big Deal”:

“One of the things we’ve seen from all our data crunching is that G.P.A.’s are worthless as criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless,” says Bock. “No correlation at all except for brand-new college grads, where there’s a slight correlation. Google famously used to ask everyone for a transcript and G.P.A.’s and test scores, but we don’t anymore… we found that they don’t predict anything.” [2]

These traditional standards of G.P.A. and transcripts emphasize that which can be measured, letting core, though often hard to quantify, skills— such as real-world problem-solving, emotional intelligence, being a team player—fall through the cracks. Google isn’t the only company shying away from these standard rubrics, either. Many companies have been placing more stock in interpersonal skills and personality traits, like curiosity and empathy, than traditional academic measurements when it comes to hiring—our own firm included. Increasingly, employers know what attributes benefit their organizations best, and how to spot it in prospective employees. The problem is, they often can’t find enough fresh graduates with the right balance of these traits.

This shortage of adequate applicants is not limited to one country, though each country’s context is unique. The United States, for instance, continually boasts high college attendance rates—90% of millennials will attend at least some college within eight years of graduating from high school—and specialized and research-based degrees from the U.S. are often unparalleled.[3] The challenge lies with students looking to enter the job market with less industry-specific degrees. Many of these grads simply do not have the skills for the jobs that are available.

Indeed, while its populace becomes increasingly educated, the United States is suffering from a growing shortage of skilled laborers. A July 2015 report found that 35% of surveyed economists had seen shortages of skilled labor the previous quarter—a 12% increase over the previous year.[4] An article in The Atlantic juxtaposed an optimistic statistic—5.8 million job postings in July 2015 (the highest ever)—with the fact that 17 million Americans are either unemployed or underemployed.[5] These statistics signal a mismatch between employers’ needs and applicants’ skills.

This shortage is shaking up the typical liberal arts approach considerably. Well-established colleges are losing would-be students to technical schools and community colleges where they can get as good an education in tech-driven programs like computer science, industrial design, and electrical engineering—often for a fraction of the cost while graduating with workplace-ready skills. The efficacy of core aspects of the undergraduate experience—lecture-based classes in cavernous auditoriums and department-specific buildings—are being re-evaluated. Many four-year schools have begun to shift their programs to respond to the market-driven needs of their current and prospective students. One such school is Stanford, who is piloting a provocative attendance model, dubbed “@Stanford,” that splits one’s undergraduate experience into six years spread over the student’s lifetime and focuses on “missions” rather than “majors.”[6]

In South and Latin America as well as Southeast Asia, the tech and manufacturing booms of the 1970s-on have created fertile economies and wide spectrum job markets—creating opportunities from basic manufacturing, to software development, to top-level management and CEO positions. In these healthy markets, the need for high-performing, fresh graduates has never been higher. These regions, however, often do not have as robust and storied a foundation for higher education as their global neighbors in the U.S. or Europe.

While there are undoubtedly some growing pains to go through as these countries expand their education systems, the relative youth of their higher education institutions represents a significant advantage and opportunity over institutions with more codified bureaucratic processes. In recent years, we have been fortunate to work with several international universities that are pioneering new directions in education. Below, we explore the specific pedagogical and spatial planning solutions at two of these schools.

One of these is the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD). SUTD was incorporated in 2009 as Singapore’s fourth publicly funded university, and developed in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The university is based on bold new paradigms for integrating technology and design education in the fields of engineering, product development, architecture and sustainable design, and information systems technology. These aspirations serve as a means to promote research and learning, partnerships with industry, and integration with a global, knowledge-based economy.

The university adopts a cutting-edge academic vision by dismantling the idea of majors and creating a curriculum that focuses on four branches of design conceived as the pillars of the university—Engineering Systems and Systems Design, Engineering and Product Design, Architecture and Sustainable Design, and Information Engineering and Design—and by promoting interdisciplinary, project-based collaborative learning. As part of this new pedagogical structure, groups of 50 students are organized into learning communities for a stretched calendar year termed “freshmore”— consisting of one freshman year and a half sophomore year. The curriculum is structured to be highly interdisciplinary and project-based, with students completing at least 20 projects prior to graduation, according to John Brisson, director of the MIT-SUTD Collaboration Office.

SUTD’s four Academic Pillars are spread across the campus, promoting cross-pollination between discipline

This new structure has direct impacts on faculty collaborations as well. Lawrence Sass, an architecture professor who spent six months at the university noted “what I really got from SUTD is relationships—it’s an environment where you can get to know people and ‘date’ other faculty that you’d never have a chance to ‘date’ (at MIT).”[7] Sass developed a collaborative partnership with a SUTD professor that led to the development of new thinking in visualizing and proto-typing large objects. The inherent interdisciplinary culture of the university actively fosters collaborations across disciplines—for students and faculty alike.

According to Chris Kaiser, professor of biology who collaborated with two other professors to design class curriculum, “these three professors from their different disciplines, maybe we have spent the most time together of any professors in those three disciplines here at MIT, in one room, working out a class.” This unique partnership between MIT and SUTD has also resulted in catalyzing changes in MIT’s ways of teaching. John Fernandez, professor of Architecture recently observed, “Many elements of [the Introduction to Design class] are coming back to MIT. This is one of the main things we kept in mind from the very beginning, is what we do there, or what we’re doing in the service of [SUTD], how is that reflected back at MIT?” There are similar examples of innovative curriculum and pedagogical methods being developed by faculty from both universities in close collaboration. Samson Lim, assistant professor of humanities, arts and social sciences observes “this collaboration really opens up opportunities for faculty, both here and at SUTD, for tinkering or experimenting with new courses, or new units within courses that already exist.”

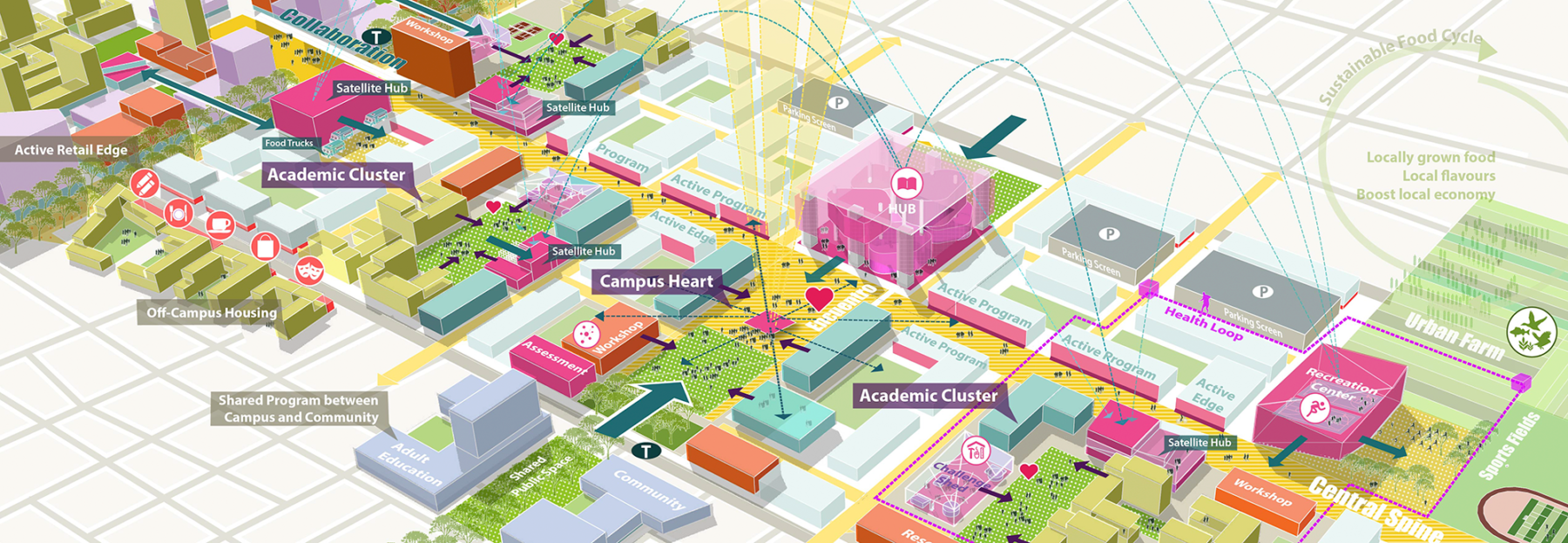

To foster SUTD’s innovative curriculum, Sasaki developed the master plan in close collaboration with representatives from MIT and SUTD to put forth a bold and visionary road map for the campus environment.[8] A key concept is the east-west pedestrian spine that showcases the university’s interdisciplinary and collaborative mission with multi-functional and interconnected academic buildings anchored by the International Design Centre and woven together by an outdoor pedestrian network. The spine also creates a public face for the university and connects to surrounding areas for future development. Student life facilities, housing, and recreational buildings will be integrated in mixed-use precincts and connected through a range of public spaces and pedestrian links. Sustainable design strategies are comprehensively integrated through building systems, green roofs, pedestrian and transit access, and stormwater management. The resulting campus has a strong identity, supports a vibrant community, and demonstrates a commitment to engaged learning and student development. The new campus will accommodate up to 7,000 students on a site area of 22 hectares.

High-activity program spaces are located on lower levels to encourage visibility and interaction; offices and heads-down study spaces are placed in more secluded areas

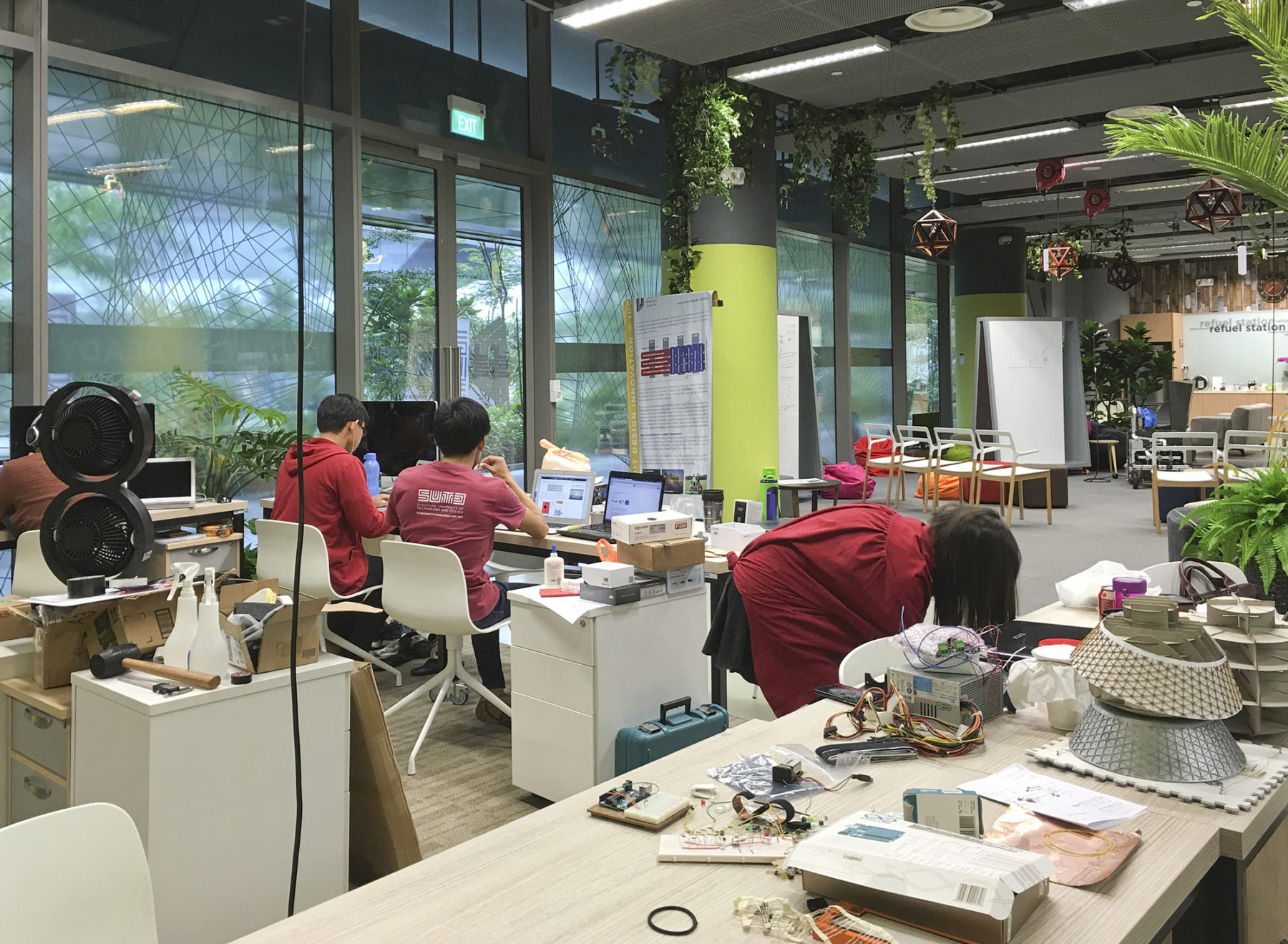

The success of SUTD’s vision of academic pillars requires flexible teaching, learning, and student life spaces that will facilitate interdisciplinary exchange and collaborative opportunities. The Design Centre—a building located at the physical and metaphorical heart of campus—accordingly features a variety of spaces for congregation and collaboration, including conference and exhibition space, studios, workshops, collaboration space, office and support space, and two auditoriums. The clusters of academic buildings surrounding the Design Centre also have a significant amount of exhibition and assembly space, as well as classroom, laboratory, and office space, to respond to the specialized nature of SUTD’s academic programs

A network of pedestrian bridges and courtyards serve as the connective tissue between buildings

Rather than grouping the pillars in distinct areas, the programs are distributed across the building clusters to promote interdisciplinary conversation and innovation. Academic spaces are placed on the lower levels of the buildings, student life space in the middle, and faculty offices at the top, with a goal of putting the most active uses closest to the spine. Each of the buildings have courtyards, light wells and terrace gardens to access air and light, and green roofs overlooking the primary spine and living-learning corridor. To further promote the exchange of ideas, the master plan connects the academic clusters to each other, and to the Design Centre. Within the buildings, a network of pedestrian bridges and entries from the underground parking knit the buildings together. On the exterior, the primary spine and living-learning corridor connect the buildings on multiple levels through a series of pathways and terraces. The frontage of the Design Centre and four pillars along these areas serves to enliven these pedestrian ways.

One of SUTD’s design-focused laboratories

SUTD is designed to be a place which is open and permeable, inviting active community engagement. The master plan vision enables the campus to be a catalyst project which brings economic and urban vitality to the eastern portion of Singapore. The proposed transit connections serve a critical link between the campus and Singapore’s Central Business District (CBD), establishing a strong campus-city relationship. The pedestrian and street networks likewise provide critical connections to Changi Business Park and the EXPO Centre, the latter of which may provide overflow space for the University to hold large-scale events. At the Changi Business Park, it is envisioned that SUTD will have a strong programmatic and physical relationship. New research and development facilities which the Park is constructing on Changi South Avenue, across from the University, may provide space for collaboration and innovation.

SUTD’s master plan celebrates connection with the surrounding communities

In 2015, Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey (Instituto Tec), Mexico’s largest private university, embarked on an ambitious program, dubbed the Tec 21 Educational Model, which seeks to rethink and consider the implications of teaching and learning methods for the entire university system. This program reflects shifts and trends in the external forces that impact the type of students the university accepts, the way that students learn, and the professionals those students will need to become to compete in the digital age. The Tec 21 Educational model assimilates the university’s current context with aspirational goals to reimagine teaching and learning methods for the entire system of 29 campuses. Sasaki worked with the campus to translate this model into spatial guidelines that enable implementation.

The Tec 21 program is a direct response to emergent approaches to learning, and the prominence of digital tools in education in an effort to strengthen those skills. Tec 21 seeks to develop a pedagogical structure that contributes to the formation of extraordinary professionals who have a deep commitment to society, are rooted in a humanitarian worldview, and have a keen appreciation of interdisciplinary and collaborative learning.

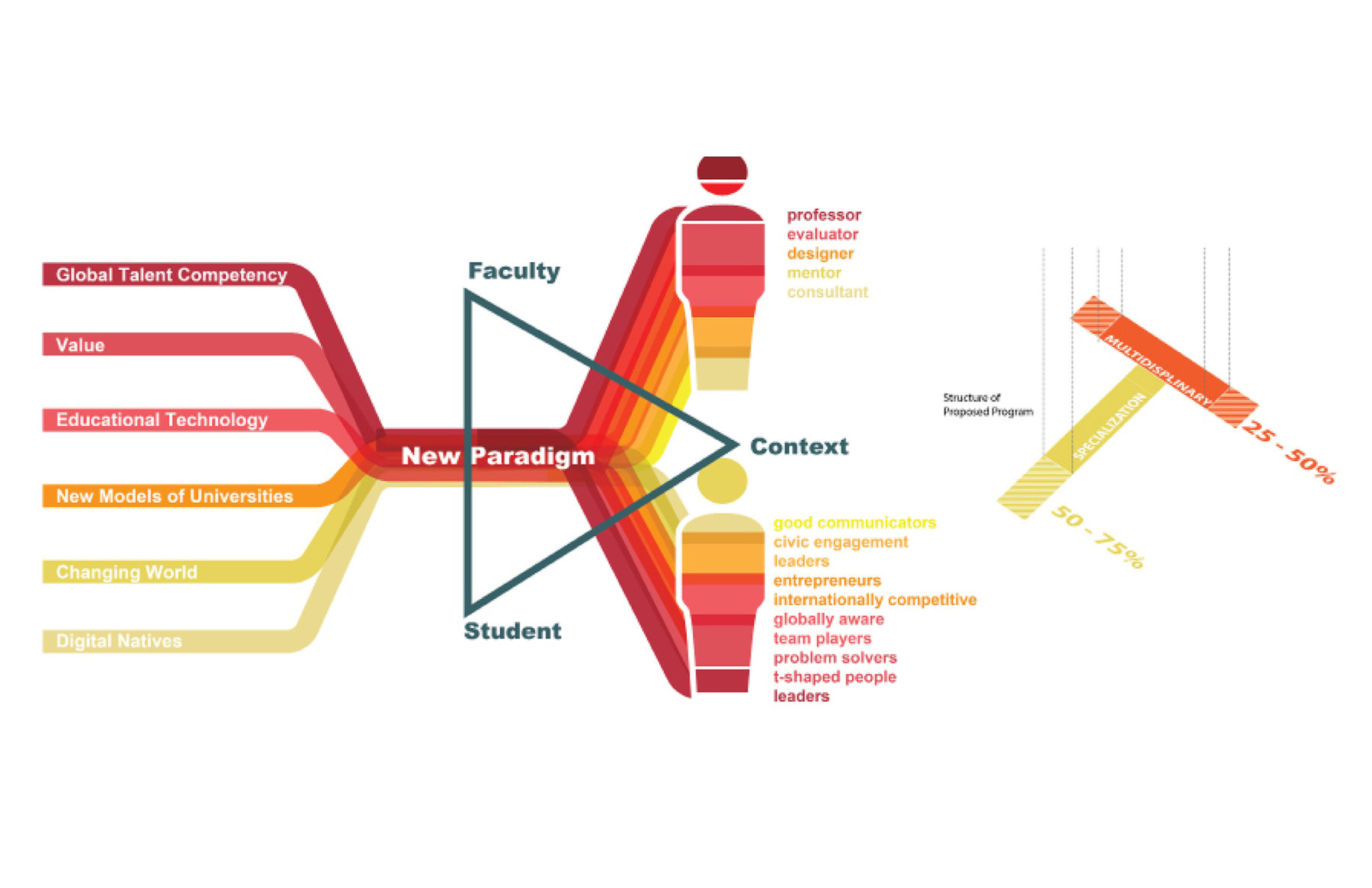

A humanitarian worldview and team-based approach to problem-solving is key to Instituto Tec’s mission

The model’s structure envisions the development of ‘T’ shaped individuals that have a depth of knowledge and skills in their core disciplines but also possess well-rounded knowledge of other related fields enabling them to become effective collaborators in multi-disciplinary teams in the professional work place. Research had shown that their current degree programs focused heavily on the “I”—the vertical part of the “T”—representing depth of knowledge. Depending upon the program, a student was expected to take roughly 75% degree-specific classes, leaving only a year’s equivalent of general classes. Tec 21 aims to equalize a student’s time invested in the “I” and the “T”’s crossbar, which represents of breadth of knowledge. While depth of knowledge is obviously highly valued, breadth of knowledge and the ability to solve-problems in interdisciplinary, team-based settings is central to preparing students for today’s workplace and society.

Tec 21’s new educational paradigm prepares students for today’s economies and cultures

A project-based approach to learning is central to the model, wherein core instruction is balanced with a series of multi-disciplinary challenges that seek to test learned knowledge and the ability to collaborate with peers. This model also seeks to create an environment that is adaptable to changing forces and is inspirational for faculty and staff. The typical academic semester is restructured, with each semester broken into three parts and balanced with a series of instructional modules and applied challenges. As students progress through a semester, the focus shifts from core instruction to greater engagement with challenges. Breaks within a semester are structured as an “Innovation Week” where all the campuses in the Tec system engage in a week-long challenge involving multi-disciplinary teams and faculty.

The role of the faculty also shifts from just delivering instruction to designing challenges, mentoring and constantly evaluating students and the pedagogical structure. The goal is to develop students into professionals who are good collaborators and communicators and have a deep respect and commitment to society. This model also redefines the relationship between faculty and students to engage a real-world situation or problem that gives their interaction a meaningful context.

Tec 21’s goal of developing multi-disciplinary “T”-shaped individuals leads to the development of a non-linear progression of study where students have enormous flexibility in molding their curriculum as they progress through years of study. This model also encourages and enables students from different universities within the Tec system to take courses at different campuses depending on their interests.

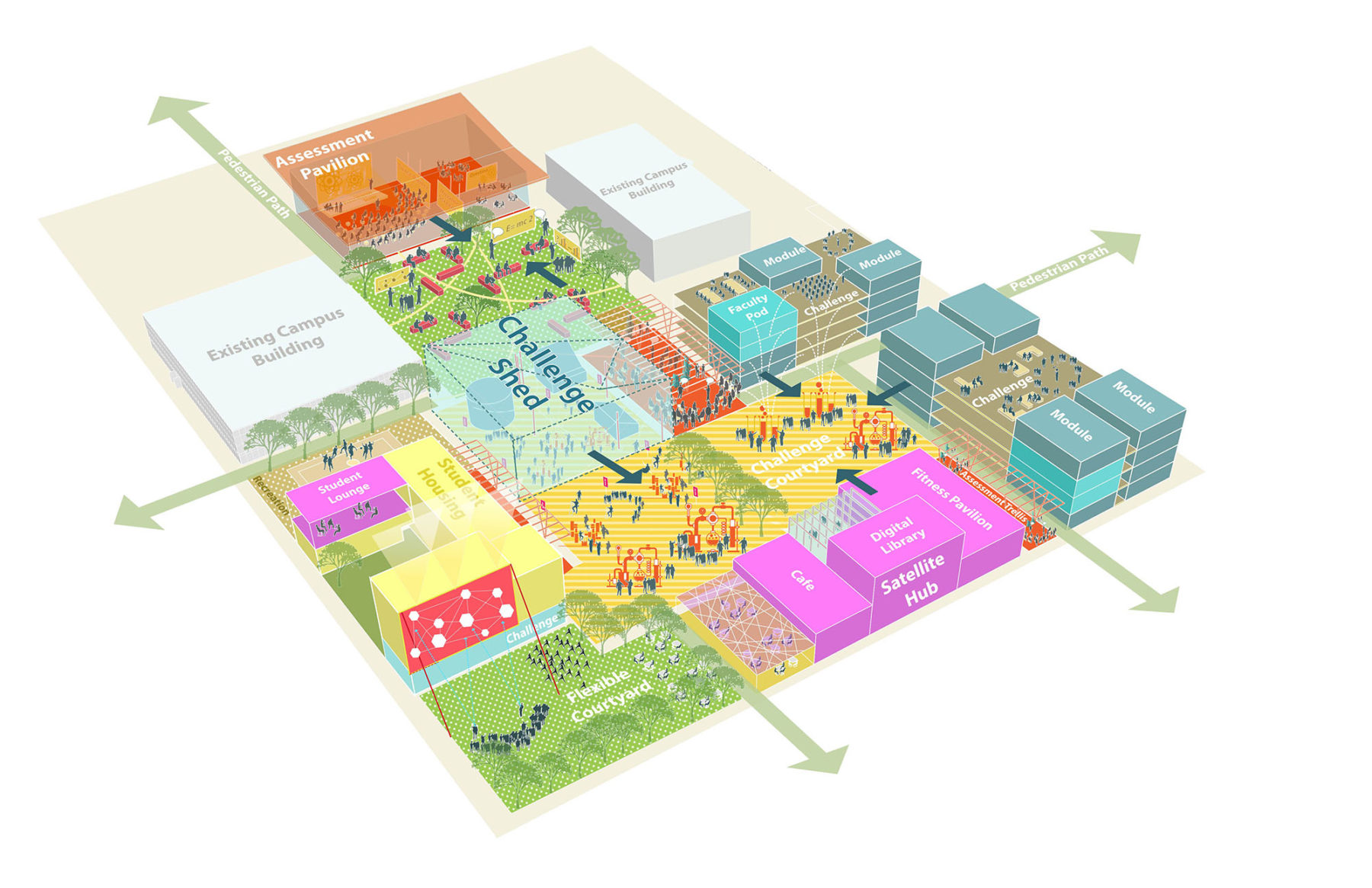

As part of the process, a robust toolkit of space types and principles are developed that reflect new thinking in the pedagogical structure as well as related impacts on the campus environment and adjacent communities. The Tec 21 pedagogical structure leads to the formation of three primary organizing elements:

Modules: these comprise of next-generation instructional and research spaces primarily consisting of versatile active learning classroom typologies that facilitate focused study in a structured environment. Typically designed to accommodate 20-25 students, the modules are located adjacent to spaces for collaborative and informal study and equipped with the necessary technology and infrastructure to support the development of specific competencies and/or disciplinary activities.

Challenge spaces: these facilitate student and faculty collaboration, project work, and brainstorming. Challenge spaces are organized into varied types ranging from a collaborative room that accommodates 2-4 students to a multi-purpose shed for larger experiments and hands-on learning. The campus landscape is also treated as a challenge space and structured to facilitate testing and research of water, planting, and agriculture systems.

Assessment spaces: these spaces are devised to provide consistent peer-to-peer feedback, faculty critiques, student displays, and exhibits. Assessment spaces are located in highly public settings to foster a culture of active engagement and are equipped with movable panels, screens, and flexible infrastructure that enables re-organization of the space to accommodate various scales of activities.

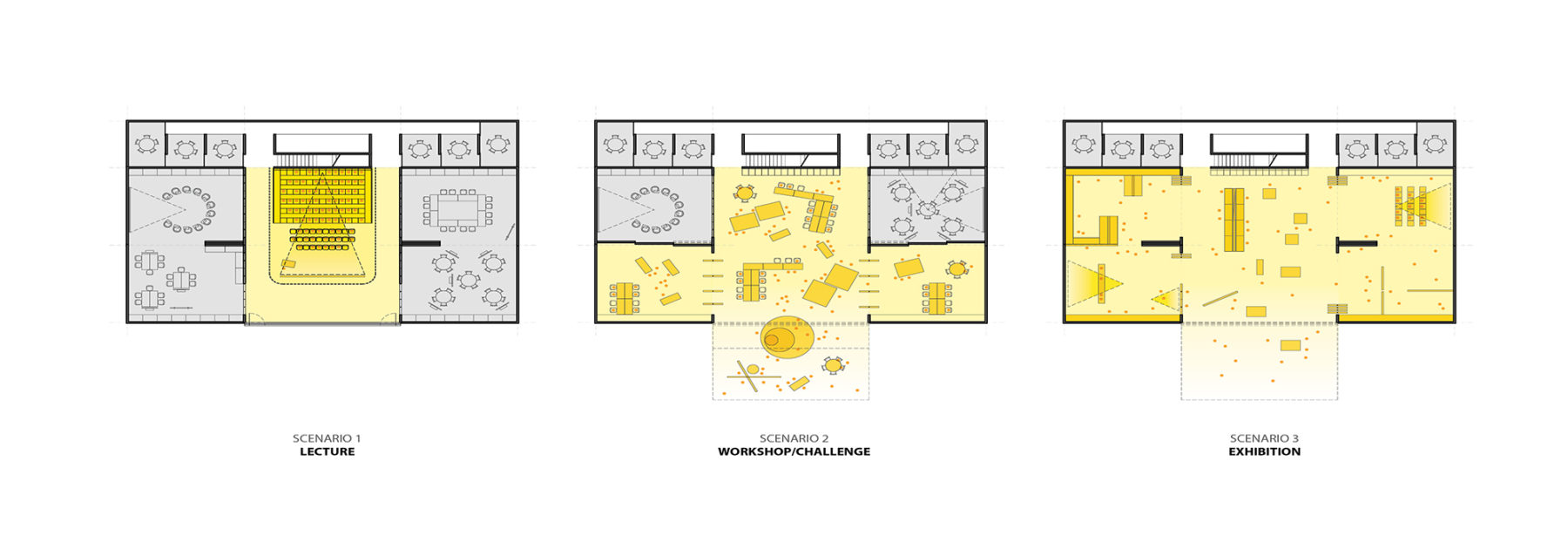

New spaces for new pedagogy: Tec 21’s curriculum creates a cycle of core education, challenge-based learning, and public presentation of solutions.

These academic spaces encourage organic interactions with the campus and peers

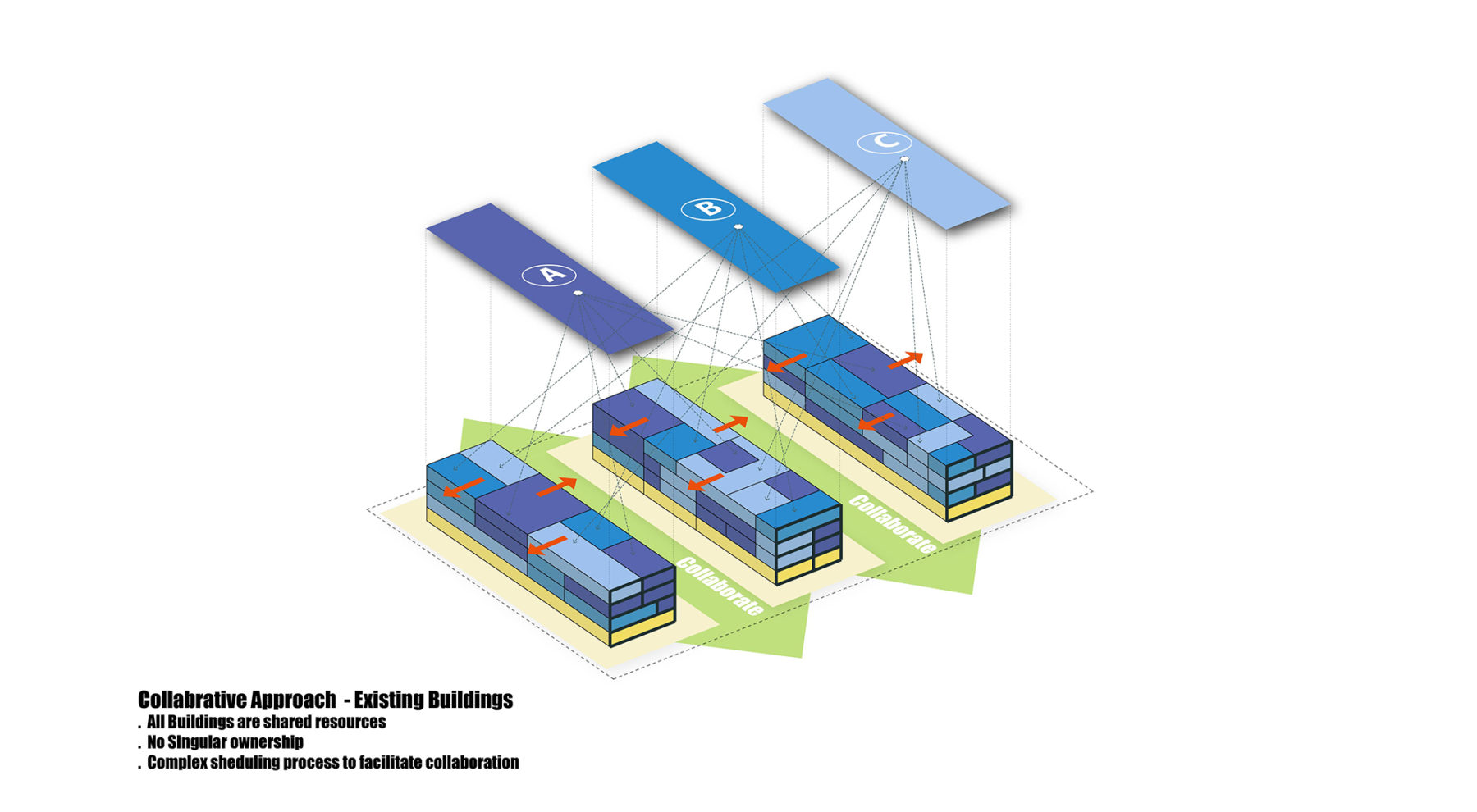

The master plan also consciously disrupts existing silos of academic departments and faculties, re-organizing them according to disciplines they collaborate with instead of the disciplines they “belong to.” A new paradigm is imagined, in which all buildings operate as shared resources without singular ownership of a specific academic department. Scheduling of classes is re-structured to provide opportunities for collaboration and serendipitous encounters between peers and faculty. Interdisciplinary and inter-faculty collaboration forms a key structuring element along with the development of spaces for student collaboration and engagement with allied industry and the surrounding community.

No more Silos: a deliberate shuffling of department spaces encourages intuitive and serendipitous student and faculty encounters across disciplines

We worked with the Instituto Tec to translate these ideas into practice by developing a robust toolkit of space types and principles that reflect the new pedagogical structure as well as related impacts on the campus environment and adjacent communities. All 29 campuses within the system were evaluated, and Queretaro—a campus in West Mexico with over 5,000 students—was selected as a pilot campus to test and integrate this new thinking at the overall campus level.

Following the selection of a pilot campus, we worked with the university’s Tec 21 advisory committee and the leadership at the Queretaro campus to articulate a clear vision that guided the overall campus framework and integration of the Tec 21 pedagogical structure.

The Challenge Shed and Assessment Pavilion become central features of campus, physically and pedagogically

A series of site visits, interactive work sessions and planning charrettes with the various stakeholders, guided the evolution of the planning process. An early in-depth mapping exercise of the campus’ characteristics, coupled with a parallel exercise focused on the overall Instituto Tec system’s operation, program, and teaching modalities, provided the basis for an understanding of the design challenge. Extensive research also included the evaluation of all 29 Instituto Tec campuses regarding their surrounding context, edge conditions, and context integration. This analysis was developed to create a series of campus-wide principles that would foster the transformation of current insular campus conditions to create engaging and active campus edges and to foster positive interaction with surrounding communities.

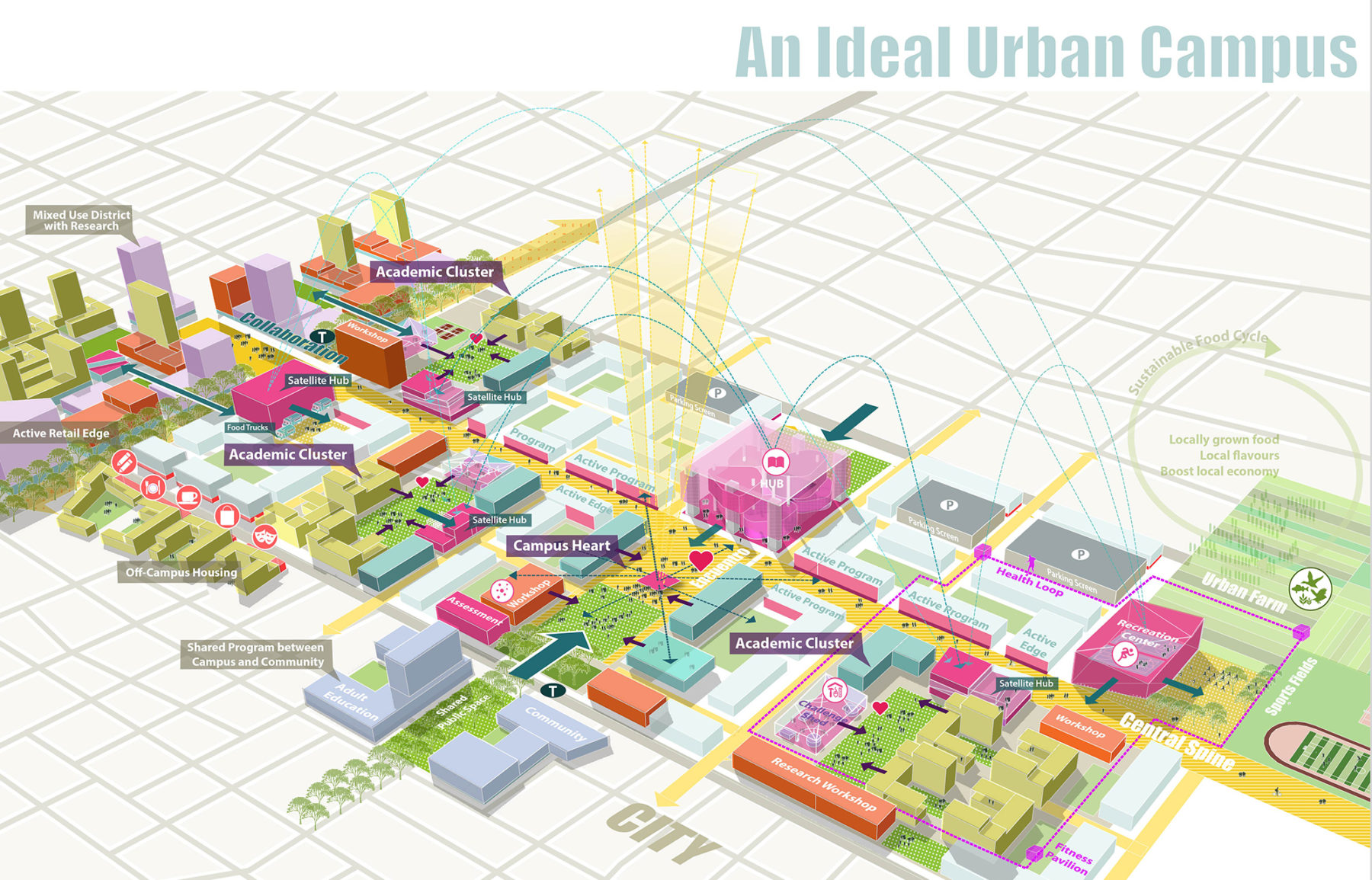

An ideal urban campus comprised of the toolkit’s many parts

The plan for Queretaro responds to its site context through a variety of conservation and development strategies, among which are transforming valuable land currently used for surface parking into a structured pedestrian-friendly public realm, increasing connectivity amongst different parts of campus, actively engaging with allied industry, and creating a framework for the integration of cutting edge pedagogical thinking.

1. Re-imagining Student Life

As part of the Tec 21 framework, a holistic framework for student development is envisioned in which the library, student dining, and student life are re-imagined. The library transforms into a hub of support for academic life on campus providing a diverse array of learning environments, academic support programs and access to library resources. The central dining facility is re-imagined as a flexible amenity that also functions as a multi-disciplinary collaborative learning and experimentation space. A series of smaller hubs that include a cafe, digital library, and recreation facilities permeate the entire campus setting creating an accessible and vibrant public realm with multiple opportunities for gathering, socializing, learning, and campus events.

2. Creating a Mixed-Use, Collaborative Environment

The campus currently has a series of diverse programs—industry research hub, high school, and an entrepreneurship development program that are isolated as individual enclaves and disconnected from the overall academic life of the campus. The proposed framework breaks down this insular structure and integrates allied industry, student entrepreneurship, and research spaces within academic and student life buildings. This conscious restructuring creates an unprecedented interdisciplinary experience for students and faculty, and will also help the campus transition into the new Tec 21 pedagogic model. The high school is supplemented by a center for adult and community education and integrated into the primary campus spine to foster seamless engagement with the campus and external community. West campus, currently a traditional Tech Park model of individual buildings surrounded by surface parking lots, is transformed into a vibrant mixed-use precinct that integrates graduate housing, research, and academics with existing allied industry spaces and the high school.

3. Creating a Culture of Knowledge Exchange

A central tenet of the Tec 21 structure is the open exchange and flow of ideas and information internally within the campus and across the entire university system. The “Encuentro” or “Place of Encounter” is developed as a new building typology that is located in the heart of the campus and forms a place of gathering, and a common ground for the entire Tec community: students, faculty, and visitors. A place of open exchange, the Encuentro supports a variety of formal and informal events and connects the Tec 21 community to the outside world—physically and technologically.

The current central pavilion that is a hub for student study and gathering is re-imagined as the Encuentro for the campus. Existing surface parking lots and neighboring underutilized open spaces are transformed to create a collaborative mixed-use heart for the campus with a central plaza. The Encuentro is also imagined as a temporary pavilion that can be inserted into the city for more direct engagement with the external community.

4. New Spatial Typologies

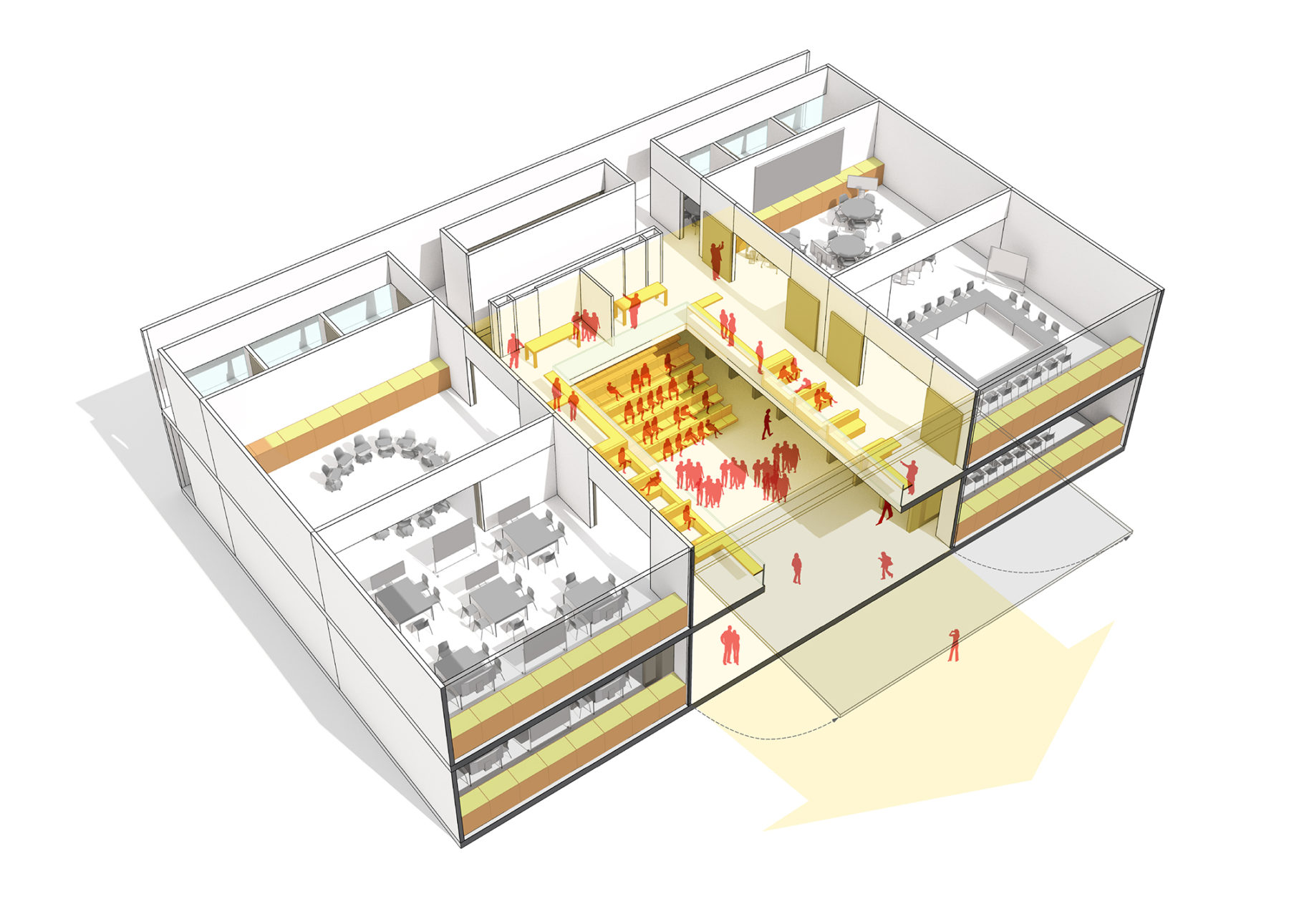

The Tec 21 structure necessitates the need for spatial typologies that are flexible and can adapt with evolving pedagogical needs. The new typology conceived consists of a series of flexible instructional spaces (modules) that open onto and engage a multi-purpose flexible space. The modules are equipped with adequate technology, writable surfaces, and movable walls to allow both active learning and collaborative student work.

The multi-purpose space in the center is designed with flexible bleachers and movable furniture that allow varied activities to take place—lectures, student presentations, end of semester student exhibits, student group activities, and so on. Storage areas, small group collaboration rooms, faculty offices, and an occupiable open learning hallway that overlooks the multi-purpose space provide support and foster a collaborative learning environment.

The “challenge shed” is conceived as a new typology of multi-disciplinary collaborative space, akin to a large flexible shed, that houses a fabrication lab, proto-typing facilities and brain-storming lounges. This space facilitates experimentation within academic departments on campus and engagement with allied industry and the external community. The challenge shed is “plugged in” to existing buildings and also attaches to new buildings forming a collaborative interface between the two.

At Queretaro, the Tec 21 toolkit and principles are harnessed to help re-imagine existing buildings and organize new building and public realm interventions within the campus. Building on the structure of the historic core, the campus is re-organized to form new integrated mixed-use clusters for academic, research, and student life, and creating a vibrant public realm that facilitates outdoor learning, social engagement, and experimentation. A defined pedestrian spine forms a collaborative armature that ties the academic core together, creates a clear heart of campus and blurs traditional boundaries of interaction between academic programs and allied industry partners to create an integrated 21st century campus environment.

It is a familiar trope that we have been hearing since the internet became commonplace in the 1990s—the way we educate students in the future will be different. Now, two decades into the digital revolution, the discussion still focuses on the future: the next few years, the next big technology breakthrough. This, of course, is nothing new. Advances in technology and the impact they have on our world is as old a theme as humanity itself. Contemplating what’s next to come is central to furthering any dialogue, but making specific investments based on these forecasts too often miss the mark or lead to early obsolescence. Instead of forecasting for the specifics of the future, the schools that are pushing envelope today are embracing the one thing that they can guarantee: that change is certain. The best way to prepare students for their lives after graduation is to prepare them to view change not as an unwelcome challenge to their skills, but as an opportunity for them to apply themselves in new and surprising ways.

There’s a variant of the old “teach a person to fish” proverb that illustrates the mission and ethos of these forward looking, self-aware schools: “Give a person a fish, and they’ll eat for a day. Teach a person to fish, they’ll eat for a lifetime. Teach them how to learn, and they will create their own solutions in the future.”

Schools like SUTD and the Instituto Tec are doing exactly that by restructuring the concept of higher education from the ground up. SUTD’s academic pillars and the infusion of campus life spaces throughout create an immersive experience that celebrates discipline-blurring encounters and increases student and faculty interactions. Instituto Tec’s challenge-based curriculum lets students work together to solve real-world problems—fostering intrinsic curiosity and a team-player mentality, all while showing the positive impact they can have on the world. These new pedagogies and spatial realizations promote the cross-pollination of ideas and give students the edge they need in today’s world. That edge goes far beyond the outmoded values of G.P.A. and transcripts. It’s not just the edge to land that first job after college, but the well-rounded, noble, and nimble mindset that will guide them through their entire lives and careers.

[1] “[Millennials] highest value isn’t self-promotion, but its opposite, empathy — an open-minded and -hearted connection to others,” writes Sam Tanenhaus in “Generation Nice: The Millennials are Generation Nice.” The New York Times, August 15 2014.

[2] Bryant, Adam. “In Head-Hunting, Big Data May Not Be Such a Big Deal.” The New York Times, June 19 2013.

[3] Kovacs, Kasia. “More people enroll in college even with rising price tag, report finds.” Inside Higher Ed, September 22 2016.

[4] “Survey shows growing US shortage of skilled labor.” Economy, July 20 2015.

[5] Fuller, Joseph B. “Whose Responsibility Is It to Erase America’s Shortage of Skilled Workers?” The Atlantic, September 22 2015.

[6] Hayward, Brad. “Exploring Provocative Ideas for Undergraduate Education at Stanford.” Stanford News, May 5 2014.

[7] Durant, Elizabeth. “Collaboration 101: MacVicar Day examines MIT’s Unique Partnership with Singapore University of Technology and Design.” MIT News, March 31, 2015. All subsequent quotes on SUTD from same article.

[8] Singapore-based MKPL Architects served as local architects on the project.

As context and constraints evolve in a university setting, it’s important to have a structural understanding of how decisions will be made

Faced with developments in technology, education systems around the world are transforming their offerings to better educate and prepare students for employment in a fast-shifting economic landscape.