鉴往知来:中国的城市复兴之路

Urban renewal in China has been interwoven with its unprecedentedly swift urbanization over the past forty years. Sasaki's Dou Zhang and Ming-Jen Hsueh reflect on the rapid pace of change and lessons learned.

Sasaki

Sasaki

We are proud to announce that two of Sasaki’s projects, the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building designed in collaboration with Mecanoo, and the Chicago Riverwalk designed in collaboration with Ross Barney Architects, are finalists for the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence.

Celebrating transformative places throughout the United States, the Rudy Bruner Awards honor designs that are socially conscious, economically innovative, and connected to their communities. We sat down with Gina Ford, ASLA, and Victor Vizgaitis, AIA, [pictured below] to discuss their inspirations, experiences, and beliefs that drive the designs for places that are transforming American cities for the better.

Q: What is an urban transformation?

Victor Vizgaitis (VV): So often when people talk about the design of the built environment, they focus on aesthetics and beauty. Those are, of course, good things, but transformation goes beyond that to radically change the perception and the potential of a place.

Gina Ford (GF): I like this word perception because urban transformations change people’s minds about a place. The Chicago River was used as an industrial conduit for many years, leaving a negative association in the city’s collective memory. But now that people can get close to the water, it is increasingly seen as a beautiful place where people want to spend time.

To me, a transformation causes people to start to value an urban resource, and encourages a feeling of ownership. In the case of Chicago, the urban transformation around the Riverwalk wasn’t just that it became popular public space where there was none before, it was that the Chicago River as a whole had a new identity and sense of potential attached to it.

VV: Since the Bolling Building opened, the community has really embraced the building. That they have claimed it as their own is a really powerful thing. There’s a pride and ownership and that translates into wanting to maintain and reinvest, and I think that kind of ownership is what sparks future transformative projects.

Q: How did you design transformative projects in areas with such rich historical legacies?

GF: In Chicago, especially at the Main Branch of the Chicago River, you can see all phases of the city’s development—from the industrial landscape of hulking metal bridges with painted rivets to the delicately ornamented Beaux-Arts spaces along the viaduct. We always saw ourselves as layering onto that and not erasing it. Our design brought 21st century concepts of ecology and recreation to the space, but our underlying design question was about how to contribute to this already layered, complex, beautiful thing—instead of creating something entirely new.

VV: For the Riverwalk, you were really building off of Chicago’s architectural legacy, but for the Bolling Building the most important driver was the history and memory of Dudley Square (renamed to Nubian Square in 2019). For much of its history, Dudley Square was a thriving community and is literally in the geographic heart of Boston. But disinvestment in the latter half of the 20th century left Dudley Square lacking transit access, public spaces, and a sense of urban life. There was a real sense of emotion tied up in this place from its rise and fall over time.

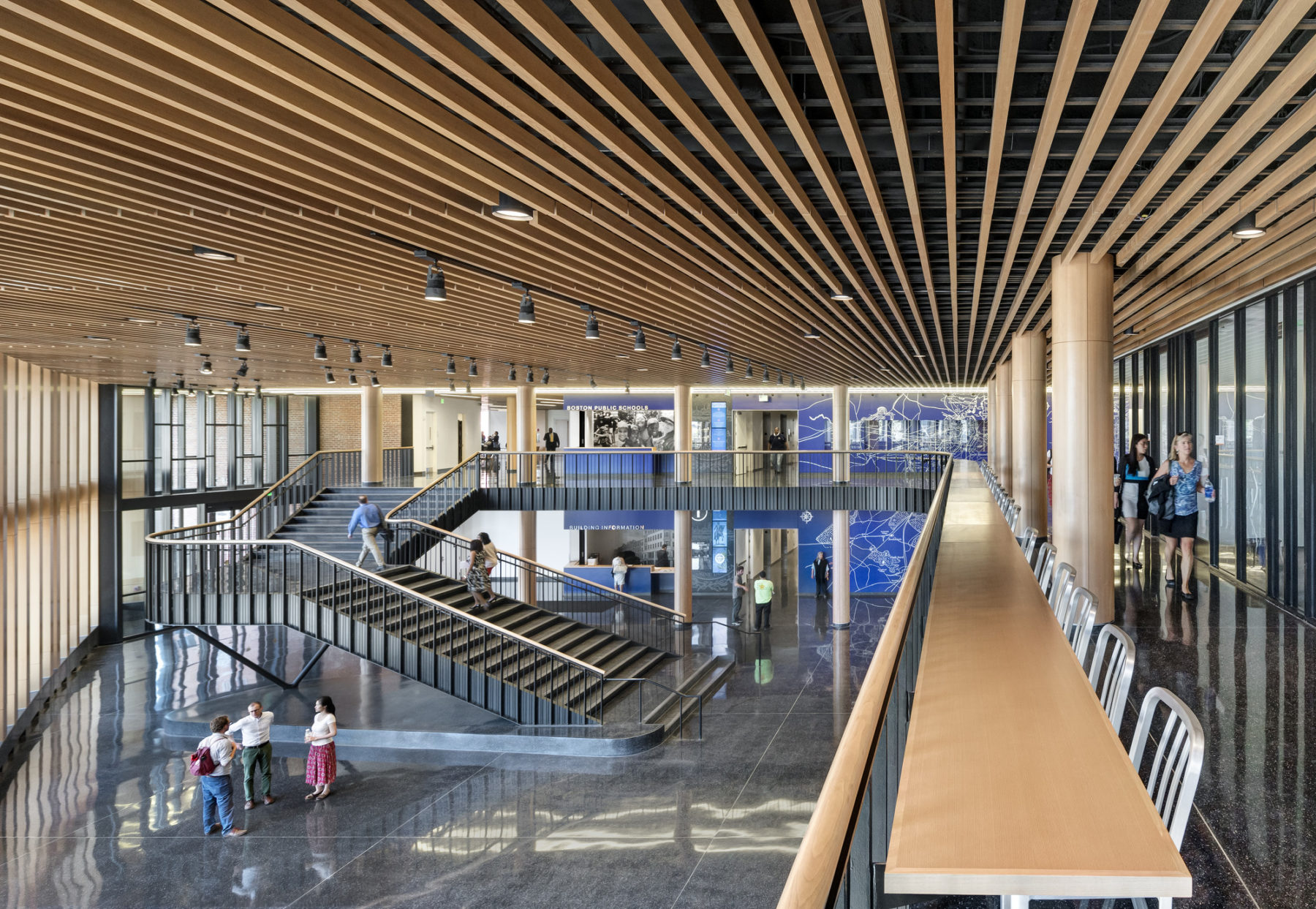

For us as a design team, the power of those emotions in the community and the memory of Dudley Square at its best really inspired us to think bigger and push our designs forward. Instead of designing just another office building for Boston Public Schools, we lobbied for a large atrium that would essentially function as a public square on the ground floor and a monumental staircase which could hold an entire choir singing. All of these features made the Bolling Building a place for the community—in service of reviving the legacy of Dudley Square.

Q: How did the designs for the Bolling Building and the Riverwalk respond to their urban context, while also anticipating what these areas could become?

GF: When we were designing the Riverwalk, we paid careful attention to the existing fabric and materiality. We chose materials that felt like they belonged to the site, but used them in a way that was new and fresh. Limestone and granite complement the elegant Beaux-Arts viaduct, and the metalwork connects to the bridge. Sometimes people can’t tell where the project starts and stops, which speaks to this feeling of connection across time and space.

VV: Creating that kind of feeling of seamlessness in the urban fabric requires looking outside of the project boundary at the bigger picture. For the Bolling Building, we wanted the project to feel like it was always a part of the neighborhood. We wanted to make the building permeable, not a monument or an icon in and of itself. Our designs were borne of this impulse to build from what was already in Dudley Square—these incredible and meaningful historical facades, a tradition of building with brick, and the square’s history as a thriving commercial and transit hub.

Q: What was it like working with a city to realize their vision?

VV: The idea that there was a vision for something transformational was what made it succeed. The design team was a translator and advocate for the city’s vision. At a few points when the project could have derailed or became mundane, we helped to remind everyone what our original goal was. We wanted the Bolling Building to be more than a just public office building. It doesn’t have a metal detector or security guard like other municipal buildings, it has a huge area of dedicated public space, and the mixed-use portions of the project are a home for local restaurants and businesses. There was a real push to make something different, all of which came from the City of Boston’s vision.

GF: Chicago—across many organizations and agencies—has been working on reconnecting the city with its river for decades. This latest stretch of the Riverwalk is about realizing an important segment of a decades-long project that the City had envisioned and permitted that had set the parameters of the project. We also had the privilege of learning from each phase of public space along the river that had been implemented before us. We had a client who had a vision and the tenacity to build a project like this. Together, we achieved the high aspirations inherent in this vision.

Q: How did you approach designing for and with the public for these projects?

GF: The Riverwalk gathered public input in different ways. It was really a continuation of multiple decades of work downtown and along the Chicago River, so we read over this research and found the shared priorities which would really drive this project. But I think, fundamentally, we thought about who the Riverwalk was serving, and that was always the public—which took on several different forms.

We recognized that Chicago’s downtown population is growing. People are choosing to live downtown where they weren’t before, particularly in the North Loop. We wanted to make the Riverwalk a place where a tourist could come and visit and feel connected, but we also wanted that same experience for residents. Since the early 2000s, Chicago has invested in a number of significant public space projects, including Maggie Daley Park, the 606 Park, Navy Pier, and the Riverwalk. Each is certainly an expression of Chicago’s civic identity, but they’re also about programming for people downtown. In this way, these spaces become an integral part of a resident’s experience of the city. These are public spaces that are your backyard if you live in a tiny apartment, they’re places where you can go on a date, practice yoga, or take your kids to play.

VV: Public engagement was so crucial to the success of Bolling Building. For a year and a half, we had public meetings every two weeks in a building across from the project site. As the design team, we updated the community on our designs and fielded comments and feedback. We really listened to the feedback and incorporated it into our designs and programming. And the City of Boston made sure that local residents were involved in the construction crews and that all of the retail that would be located in the mixed-use portion of the building was local business—not national chains. All of these elements were discussed throughout the public engagement process. There was a palpable sense that both the design team and the city were inviting the community in to design with us, not that we were just going put a monument in their neighborhood.

Q: What do you hope for the future of these projects?

GF: In some ways, the Riverwalk was the end of a decades-long process to transform the Chicago River into a public amenity. But I still think that its success will continue to impact the urban landscape nearby. Rahm Emanuel just announced an Urban River Edges Ideas Lab to explore potential designs for other areas of the Chicago River. When you have success at each phase, it leads to something else, the next big thing.

VV: I hope that the goals of this project aren’t forgotten. I want the first floor to remain public, for there not to be a security guard—I hope that people keep pushing for this vision and the city keeps protecting it. I think the Bolling Building was just the beginning of Dudley Square’s transformation. But it’s not just about one project, it’s the work of decades, and I’m truly excited for Dudley Square’s future.