City of Little Rock Downtown Master Plan

Little Rock, AR

Sasaki

Sasaki

Whether in his hometown or in an unfamiliar city, urban planner Daniel Church understands the importance of the memories people associate with places in their communities. By balancing multiple perspectives, Daniel weaves together different scales of thinking to develop plans that strive to improve quality of life for all by devising creative solutions to large-scale infrastructure needs.

Daniel is closely involved in Sasaki’s downtown planning projects in Little Rock, Denver, Oklahoma City, and Tulsa. He maintains a keen pulse on the changing landscape and character of downtowns across the country, driven by a belief that investing in downtowns is critical to preserving cultural life and charting more sustainable futures for cities.

Tell us about your background. What drew you to planning?

I think in many ways I was always meant to do this, and I feel really confident in saying that. Growing up, I split my time between drawing buildings and playing with kids in the neighborhood in the woods behind my house. I made myself mayor and made them all city council members—that’s how I organized my world.

In high school, I started getting really into sustainability and realized that was something that I felt called to do at a higher level. I studied environmental policy at Sewanee: The University of the South for my undergraduate degree. It’s a college in Tennessee that Sasaki actually did the campus plan for two years ago. I loved the interdisciplinary nature of my liberal arts education there.

I had thought about going to undergrad for architecture and decided not to, and when I was coming out of college in the peak of the Great Recession, unemployment amongst architects was quite high. So I decided to start a graduate program in environmental policy at Duke, but didn’t feel like it was exactly the right fit. Fortunately, I took an urban design class that really confirmed that this is what I was meant to do. Even the professor urged me to go to school for planning instead, and that’s how I shifted course, and changed graduate programs to UC Berkeley.

To be honest, I didn’t even really know that planning existed as a career path until after college. I think some of that was due to growing up in Arkansas, where “urban planning” is not really part of the vernacular. But I’ve always been really interested in the intersections between sustainability, transit, housing, and how people use public space. After graduate school, I worked for the City of Dallas for seven and a half years for the Planning and Urban Design Department, where I managed the city’s urban design review process, led area planning efforts, and worked with the public works department to improve the city’s streets.

You mentioned that planning isn’t really part of the vernacular of where you grew up in Arkansas, but I imagine your natural surroundings were very much part of the vernacular in ways that aren’t often the case in more urban areas.

I was an Eagle Scout and spent so much time outdoors that I think from a young age, protecting the environment was pretty instilled in me. I remember seeing how suburban growth caused the destruction of natural areas in my hometown. And even as a middle school and high school student, I inherently knew that something about it felt wrong and that we could do better, without really knowing that there’s this whole world of urban planning that speaks to these things.

What kinds of challenges do you face in the planning process, and how do they shape the way you work?

We work with existing constraints—whether it be the physical site, roads and other infrastructure, zoning, or the need to protect a natural area. Ultimately, we use these constraints to help us develop stronger, more interesting designs because we’re making something that’s informed by the surrounding and local context.

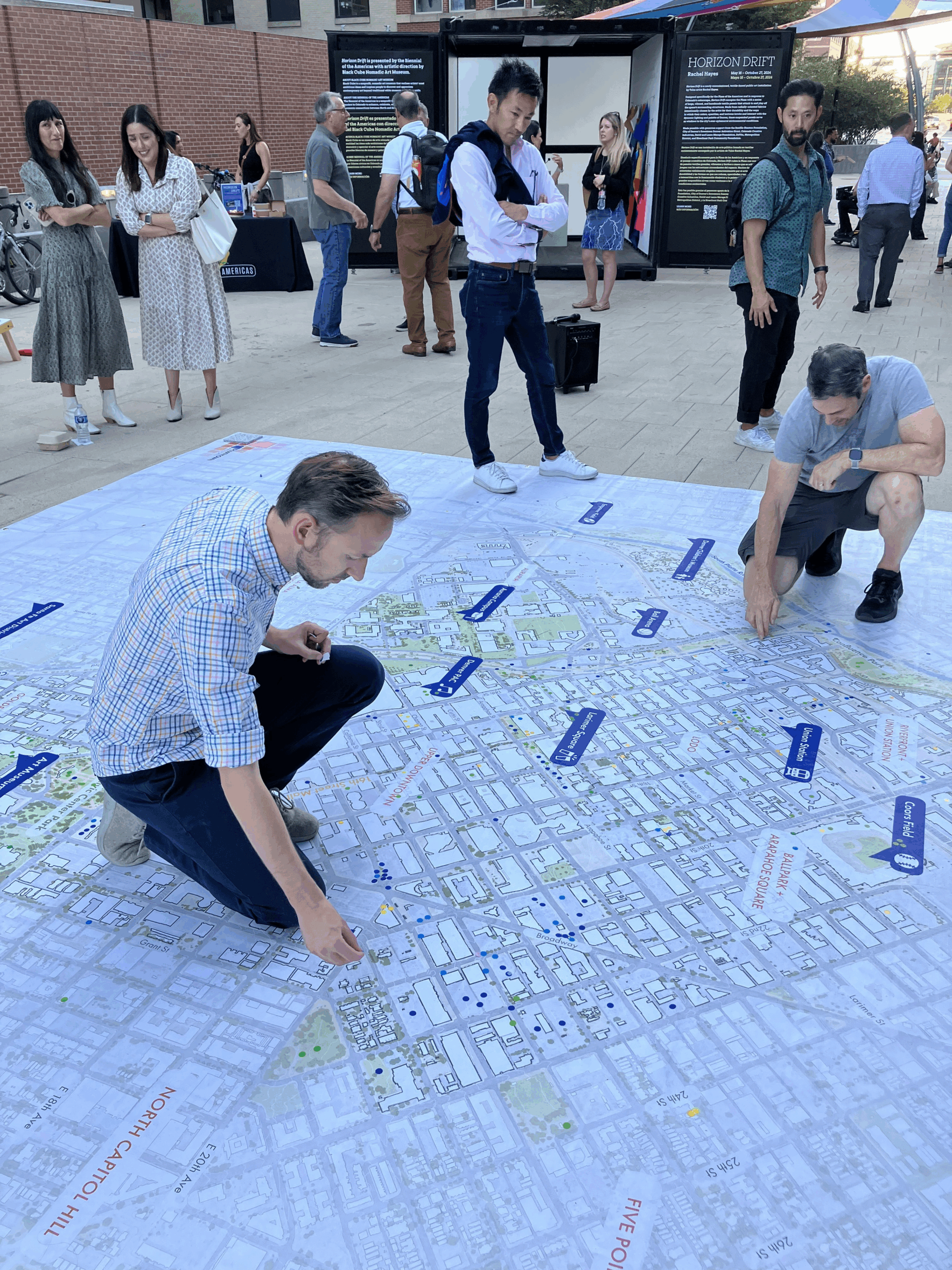

In a similar vein, I find engaging with communities to be deeply influential and rewarding. We are working to understand everybody’s unique point of view, and incorporating that into a process is essential for that project to become the best version of itself. It will also result in something that enhances the quality of life and experience that every user will ultimately have.

That’s the common thread that I always try to weave into my work; improving quality of life, and I do that by drawing inspiration from each place I work. That can include ensuring safety, affordability, or delivering a high-quality public realm and open spaces—it can mean any number of things to any number of people, but improving quality of life is central to that narrative.

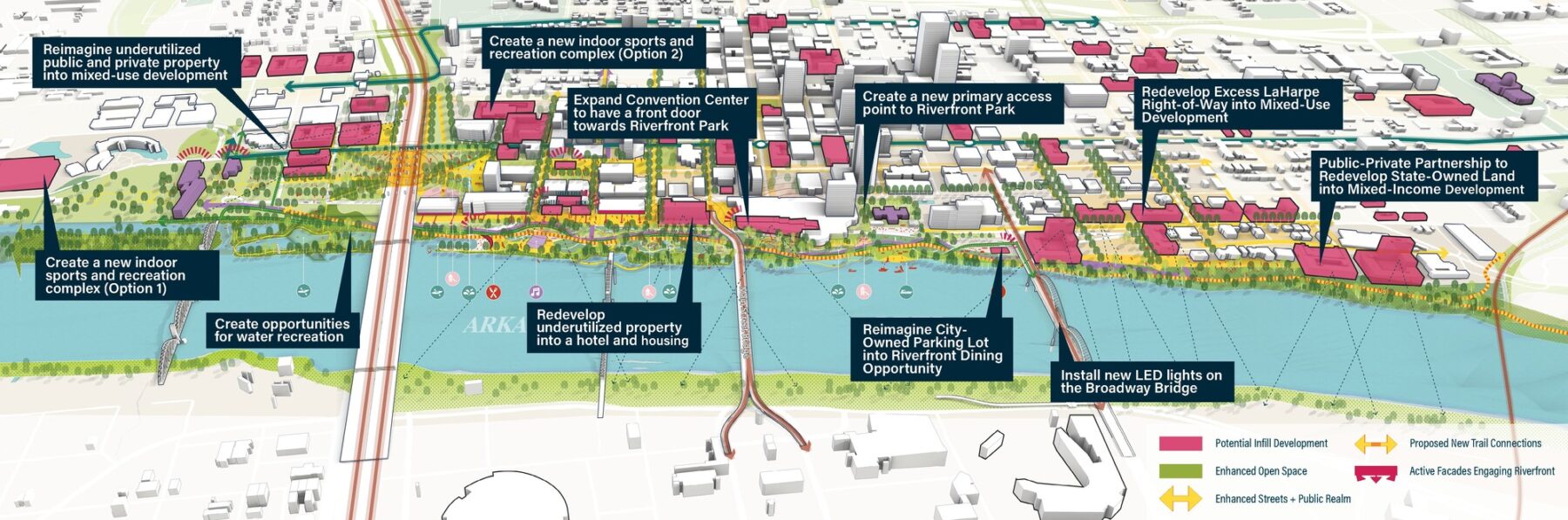

The Downtown Little Rock Master Plan focused on areas for cultural, commercial, and residential development in key areas, including along the Arkansas River and on available public-owned land.

Are there any projects in particular that have been memorable or generative for you?

The most fulfilling project I’ve worked on at Sasaki is the Downtown Little Rock Master Plan. Little Rock is my hometown, so it was a full circle moment. I’ve worked around the country and I haven’t lived in Little Rock since high school, but my parents are still there and I still have friends there; it will always feel like home even if I don’t live there.

But to take all of that and work to deliver the first-ever downtown plan for the city—beyond just being fulfilling personally, I think it was an immensely successful process and project that really worked across a lot of stakeholders. It’s a city that has a really challenging racial history that I think our project took on board and did an effective job in working through.

One of the great things about the plan is that, in addition to providing a great roadmap for the City and the Downtown Partnership, it led to a priority implementation project to build a new park downtown. The removal of some highway off-ramps freed up space that couldn’t be used for development. Immediately after the Downtown Plan process was finished, the City hired Sasaki to continue working to design what will be an amazing 18-acre park in the middle of Downtown Little Rock.

It’s exciting to see a plan turn into a project, but it’s also exciting to have a little bit of my fingerprints on something in my hometown that all started from the big ideas that come from a planning process.

Engagement sessions with Little Rock community members were instrumental in defining priorities and shaping the plan.

Given your existing relationship to the city and the personal ties you have to different places and neighborhoods within it, what was it like seeing it now through the lens of Sasaki and the planning process?

It’s funny, I remember when we were down there for the project interview, we were walking around downtown the night before and I was pointing out buildings and telling stories–“that’s where my prom was…that’s the auditorium my sister graduated in,” and so on. It definitely was personal in many ways, and many of the ideas that are in the plan were conversations that had been taking place amongst the community for years–conversations about better connectivity to the river, adding more housing downtown, and creating a more vibrant neighborhood.

It helped that I could understand some of the players and stakeholders’ points of view a little differently and more deeply than someone who might have come in and worked in a random city for a year.

But I also think there were times that it was good to have the outside perspective of others within the firm. My judgment could almost be too clouded because I would know somebody’s backstory, while others could help contextualize how we were working in this city in relation to other cities we’ve worked with.

What excites you most about working in downtown planning, and how you see the field changing, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic?

I see downtowns from two perspectives. From an environmental lens, they are the most sustainable place in any city. They are the most walkable, most transit connected, and most energy efficient parts of cities. So if we’re purely looking at things from a climate angle, focusing our energy as planners on downtowns is essential.

But we also need to be focusing on downtowns because they are essential to the stories that we tell ourselves about the places we live and why they are important to us. Downtowns are the cultural zeitgeist for a region, and I don’t know of a downtown that exists that isn’t located where the city was founded. There’s cultural energy and history there, and all the things that come with history–painful moments in tandem with celebrations.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the way that people interact with downtowns. We’re at another pivotal moment where return-to-office will never return to what it was before. While it used to be that you’re at your desk from nine to five, then pack up and go home, people now trickle in in the morning or leave at different times. The ways in which people engage with office environments are different and the pulses of downtown have changed.

The Denver Downtown Area Plan will propose recommendations for all of the city’s major neighborhoods to help pivot the urban core away from the role as a Central Business District and towards a Central Neighborhood District.

Public engagement sessions with Denver community members have focused on centering equity in the planning process.

All of this speaks to the need for downtowns to solidify themselves more as neighborhoods and less as central business districts. Housing, parks, and amenities are all important for encouraging people to live downtown. Downtowns are always going to be denser than the neighborhoods around them, but they can and should be high-quality places that are compelling housing choices for people looking to move to a given area.

The great thing is that all the traffic models that have shaped street designs and made our cities horrible are completely thrown out of the window now. Rush hour traffic isn’t as big of a deal as it used to be, and the commuting window is generally more stretched out. This gives us more flexibility in thinking about the potential for downtowns and helps us be more creative in reimagining the public realm of our cities. It is very exciting for us to fundamentally rethink how we design and plan for the future of our downtowns.

What advice would you give to people who are interested in the field or just getting started?

Say yes to everything–in terms of the kinds of planning work or design work that you may get thrown at you, whether it be campus planning, private development or civic planning work. You should try all of them. You may not like one of them, and that’s fine, but you need to learn what you’re most interested in, and you’re only going to do that through experience.

Every planner I’ve ever talked to came to the discipline from a slightly different angle. And that’s why I love planning: it is so interdisciplinary! But planning is one of those things that I don’t think young people are as exposed to at a young age, so people find their own way into it. I like to think of it as an interesting maze to navigate through. And I’m still in that maze! Maybe I’ll get to the end when I retire, but it’s never-ending, and always dynamic. It was before I became a planner, and will be long after I’m finished.