Zero Net Energy Without Adding Zeros to Cost

Reaching an ambitious sustainability goal at Bristol Community College

Sasaki

Sasaki

A recent front page article in The New York Times paints a striking image of Northeast Ohio’s economy. Manufacturing jobs, long the calling card of the region, saw a decrease of some 40% since 2000, while healthcare jobs have spiked 30% in the same period of time. This shift, though perhaps more pronounced in the Rust Belt, has taken hold all across the country. The implication is clear: the healthcare industry has become a major engine for our national economy, often filling in the gaps left by other industries.

This growth doesn’t stop at the hospital’s door—the increased economic importance of healthcare is transforming the educational landscape, too. The industry’s growth necessitates academic health science programs that can train a steady stream of practitioners—from doctors and nurses, to EMTs and hospice care providers. These programs will be critical in meeting current demand and projected shortages in the talent pool. One recent article in The Atlantic cites that 1.2 million openings for registered nurses alone will open up between now and 2022.

This growing demand is certainly not lost on schools. Leading schools in this space are instituting cutting-edge programs that blur the lines between research, clinical practice, and technology. Many schools are starting new, or expanding existing, nursing and med-tech allied health programs. Many programs are turning traditional teaching methods on their heads to better enable graduates to hit the ground running as they leave the classroom behind and step into the hospital ward setting. Whatever form they take, the proliferation of academic health science programs, and the opportunities awaiting their graduates, has impacted practically every corner of the country.

To fully capture the possibilities of expanding academic health sciences, institutions must consider many angles and multiple scales: from a region’s economic policies, to the history and organization of a campus, all the way down to an individual building and its mix of labs, classrooms, and informal space. There is no one-size-fits-all solution—a simple fact that liberates each institution to celebrate their unique identity and focus on their own strong suits. Below, three of our practitioners explore important factors to consider in defining the settings for hands-on medical education and training, through the lens of pedagogy, campus planning, and design.

By Jane Kleinman. Kleinman is Sasaki’s Director of Health Sciences and Experiential Learning. With over 25 years of experience in the medical and education field, Kleinman contributes an in-depth understanding of how to integrate efficient operations with visionary innovative program development at the intersection of pedagogy and space design.

In recent years, the complexity of medicine has begun to exceed the capabilities of individual practitioners. The borders between “health” and “wellness” are dissolving, and hybridized roles and expansion of existing roles as well as specialization are proliferating. The result of these evolutions are clear: the coordination of care among diverse practitioners is a critical need. People are living longer, healthier, happier lives due to more preventative care, better condition-driven care, and a more holistic view of what it means to be “well.” These expanding definitions have several implications on the way that healthcare is delivered, and therefore, how it is taught.

Students at Methodist University’s Thomas R. McLean Health Sciences Building practice hoisting a simulation robot onto a stretcher

As an individual may keep a stable of regular care providers for a variety of services, these providers must increasingly function as a team across the continuum of care—from fitness coaches to mental health providers to general practitioners, and so on. Therefore, the level of patient care coordination between providers is growing in terms of volume, diversity, goals and granularity. Traditional models of health science education are not set up to teach this “team sport” approach. This is further compounded by large enrollment surges to meet workforce demand, which limit students’ access to required real-life clinicalltraining.

A rapidly evolving effective response is the new pedagogical model of immersive simulation. Increasingly recognized by professional licensure boards as an important curricular component, this unique experiential learning model provide learners with a high-fidelity re creation of variable patient care challenges and settings. That has led to different space, operational and faculty focus needs.

What unfolds in these spaces is similar to a play—complete with directors (faculty), actors, an audience (learners), and a post-performance review (debriefing). The typical simulation setup has three distinct but neighboring spaces: a control room, a patient care experience room, and a viewing room. Two to three learners from a group of eight to then are selected to care for the “patient”—either a simulation robot or an actor. Faculty in the control room then trigger events that the learners must respond to in real time. Their peers in the viewing room watch the encounter unfold on broadcast screens. Following the completion of the experience, the full team regroups to debrief, with the aid of video replay, on what happened, what went well, and what could be done differently next time.

Simulation classrooms enable students to synthesize the theoretical with the applied. Here, two students interact with an actor in a realistic exam room setting

There are several benefits of this experience for learners, not least of which is the disruption of the traditional lecture-driven approach to teaching. Hands-on, team-based experience bridges the gap between the theoretical and the applied—a critical step for students to synthesize their knowledge and perform in a fast-paced environment. Comprised of any mix of medical, pharmacy, or nursing students, the learner groups enable knowledge transfer from peer to peer—driving up each students’ ability to holistically consider a patient’s condition.

The efficacy of academic health science education is so closely intertwined with the wellbeing of our people, our nation, and our world. Institutions must continually search for new ways to improve their programs to prepare their students not only for academic excellence, but for the delivery of high-quality care in the real world. Immersive simulation classrooms augment clinical placements and provide specific experiences that cannot be guaranteed in a clinical setting.

By Tyler Patrick, AICP. Patrick is a Sasaki planner and principal who has managed a wide range of campus planning efforts throughout the nation. He is dedicated to creating achievable planning solutions and seeks to advance the academic mission of the colleges and universities with which he works.

Recent evolutions in health science education have made campus planning more important than ever. As programs increasingly mix and mingle, the traditional divisions of space begin to blur. What spaces will enable these integrated environments to thrive? Are some spaces unnecessary or redundant? By analyzing a school’s existing health science programs, we can uncover mutual interests, overlapping pedagogies, and demands for similar types of spaces. In this way, the planning process helps identify the specialized needs that support different disciplines, as well as latent opportunities for sharing space and equipment.

There are myriad considerations to look at in any planning project. For the purposes of this article, let’s look at two categories: stakeholder input and spatial analysis.

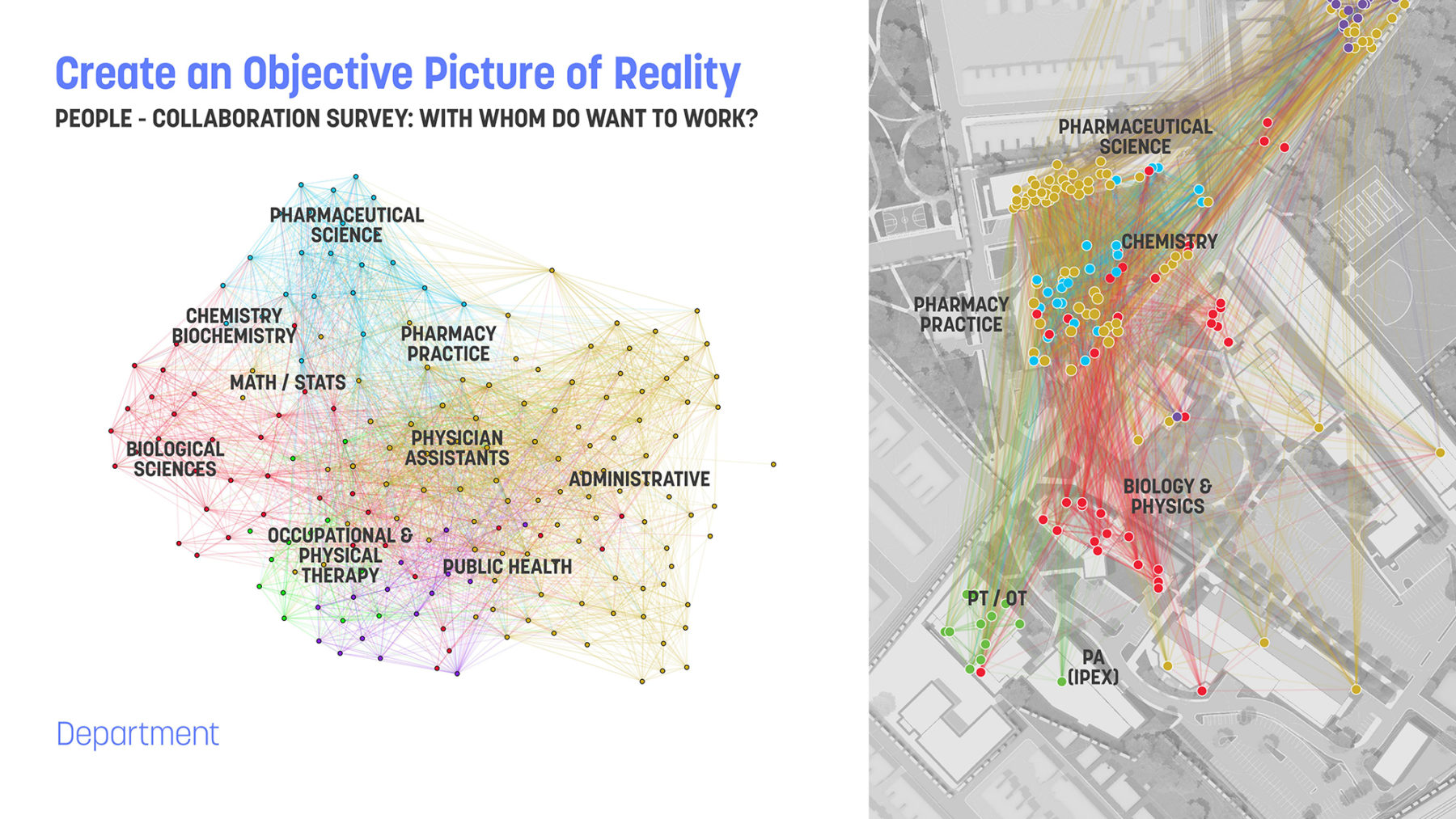

Stakeholder input is an indispensable part of developing a successful master plan. We continue to iterate our approaches to gathering this feedback, developing a specialized kit of tools that enable us to gain insight into an institution’s goals, or to shed light on underlying issues holding them back from success. Our Collaboration Survey, for example, allows us to identify how individuals work with one another across traditional departmental boundaries, both today and aspirationally in the future.

Data from a Collaboration Survey for the University of Sciences in Philadelphia. Each respondent is shown as a dot, while the lines show each instance of collaboration within and across disciplines

Quite often, individuals work across departmental boundaries to address thematic issues. This is especially true in the health sciences, where research into a particular disease may involve more than one health science discipline, or might address broader issues, such as the patient experience. Once we understand the nature of these collaborations, we can explore the potential physical implications of such collaboration. Does collocation make sense? Are there ways to optimize shared, core facilities? Are there opportunities for hoteling or touch-down space that encourage serendipitous encounters?

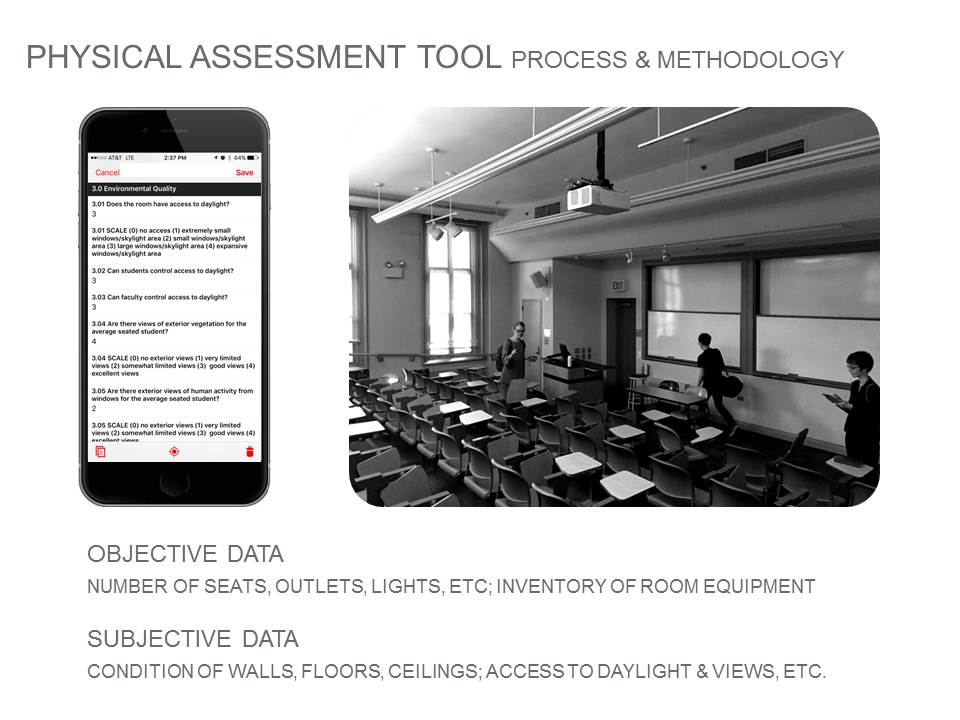

Before you can confidently plan new spaces, you have to have a clear understanding of the spaces you already have. When looking at existing space, traditional space data only goes so far. The data can tell us a lot about the quantity of space, or the intensity of the use of space, but we often don’t get a sense of the quality of space. Most qualitative space analyses are done at the building level, and they focus on things like infrastructure, and exterior building conditions. These are all important categories, but they don’t provide the full picture.

We use a custom-built mobile app to grade every room along objective and subjective parameters of quality

In our learning space and health science master plans, we assess each room to understand its performance relative to environmental considerations, furnishings, technology, and layout. By assessing these characteristics, we understand more about the learning environment, not just the general architectural or infrastructure components of space. We can then use this information to understand and determine the extent to which a relationship exists between use of space and condition of space.

Combined, these quantitative and qualitative analyses paint a more holistic understanding of existing conditions and allow us to formulate customized and specific strategies for renovation and reuse. This is why it’s so important to link planning and analysis to architecture. We work along this continuum, providing specific implementable solutions to the issues we uncover during the analysis phase.

By Tom Simister, AIA. Simister is a Sasaki senior associate and architect who believes in a systems thinking approach to design that enables learning and discovery to evolve beyond disciplinary boundaries. Raised in a family of chemists, engineers, and educators, Simister is particularly passionate about planning and design for STEM and health education settings.

Architects have a unique opportunity to help clients advance operational, technological and pedagogical goals through impactful building design. Achieving these goals contributes as much to the success of a project as traditional considerations of form, site, and program. Failure to focus on these factors risks investing in spaces that leave faculty and staff overworked and undermined, while rendering a less-than-optimal educational experience for students. What, then, are the key considerations for enabling operational, technological, and pedagogical advances during the design process?

Perhaps I can identity a few of these considerations through reverse-engineering. I recently had the opportunity to tour a new classroom that had eight $20,000 state-of-the-art group learning stations arranged in rows facing the front of the room. At first glance, this was an impressive array of technology and furniture systems that truly embodied the next wave of classroom design. And in some ways it is! However, as I looked closer, I saw that there were many preventable issues with this specific implementation.

The front-facing configuration goes against the intent of the furniture system, which is meant to line the perimeter and focus energy on the instructor in the room’s core. Next, due to this arrangement, the computer monitors block sightlines between the instructor and students’ faces. This issue forced the school and furniture vendor to develop a custom solution for lowering the monitors. Additionally, the systems are unmovable, preventing flexible configurations for varying modes of instruction. Lastly, these rooms, for all their investment in technology, have no windows—disconnecting students from the outside world and natural light.

Adaptability is key. Classroom desks at Methodist University’s Health Sciences Building double as exam tables for in-class exercises

In all likelihood, these issues arose during the design phase. So how could these ideas be prevented? Before a designer can provide appropriate design solutions, they must gain a deep understanding of the clients’ needs. This is especially important for academic health science programs which find themselves at a key stage in their evolution. More specifically: as team-based pedagogies evolve from aspirational to requisite, faculty often view the adoption of these ideas and systems with a mixture of reluctance and excitement.

The root cause of this disparity is often a lack of understanding on what these changes mean for classroom dynamics, leading to a mixed levels of buy-in and ownership. Too often, the “squeakiest wheels” get greased, which often represent anecdotal issues—not sentiments shared by a majority of stakeholders. In the example above, for instance, the front-facing configuration was chosen over perimeter configuration primarily because some faculty expressed discomfort at the thought of teaching from the middle of the room. This, paired with pressure to implement new systems quickly without sufficient test-fitting results in a classroom that works for some, yet fails to capture the full potential of this innovative and expensive furniture and hardware system.

Additionally, high-tech room configurations cannot distract from the basic elements that make spaces comfortable and habitable. Rooms lacking natural light have been demonstrated to negatively impact students’ abilities to learn and concentrate. These are simple, timeless truths but are often overlooked.

Corridors and huddle spaces at Methodist University’s Health Sciences Building maximize daylight and encourage serendipitious encounters

One way in which we source feedback during the design process is through our MyBuilding survey. The survey visualizes qualitative data on how stakeholders use the spaces within an existing building—often revealing space shortages, abundances, and unexpected uses. The data output from this survey helps leadership make informed, confident design decisions. While there are many other variables that impact the design of academic health science buildings and spaces, designers must play their part. The best solutions come from objectively understanding the client’s real needs, and that understanding can only be gained through listening.