What’s Next for Large Public Green Spaces in Shanghai?

Sasaki

Sasaki

This article excerpt by Dou Zhang, co-director of the Sasaki Shanghai office, was originally published in Landscape Architecture Frontier (LAF). It explores some of the major issues Shanghai faces such as land reclamation and ecological deterioration, as well as several strategies that would significantly mitigate these issues. Zhang delves into projects like Lingang’s Green Ring Park and EXPO Cultural Park, suggesting that through high-level strategic planning, landscape architecture can address both the needs of growing populations and support natural ecology.

To read this piece in full, please access the 30th Issue of LAF.

People in Shanghai are facing dilemmas of limited space and constantly increasing population. With over 24 million permanent residents, Shanghai has the greatest population density and smallest land area (6,340 square kilometers) among the four municipalities directly managed by the central government. Where can more space for growth be found? In recent years, cities have turned their attention to both bordering agricultural land and the ocean.

Mega-scale landfill projects “reclaim” land from the ocean for new development or even sometimes completely new cities. Lingang New City—with a project population of 830,000—is one such city, erected on top of 133.3 km2 of landfill in the East China Sea. These land reclamation projects, however, are often ecologically disruptive. Decades of landfill has created more overall area, but this land comes at the high price—each hectare gained leaves behind destroyed or severely degraded coastal habitats in its wake.

In many parts of the country, this reclaimed land area has also struggled to propel the desired urban development. This is primarily due to the harsh environmental conditions generated by this blank-slate approach to creating new land. To solve these challenges, careful planning and landscape interventions can have a transformative effect.

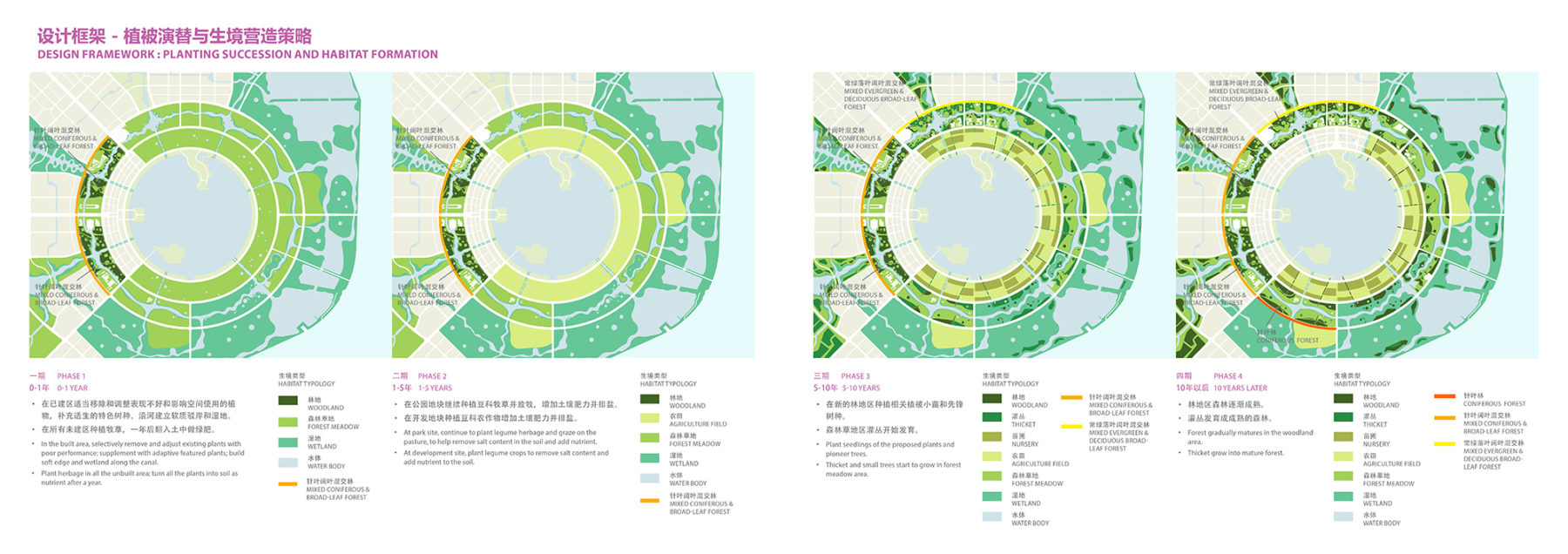

In 2015, Sasaki participated in a design competition for Lingang’s 546-hectare Green Ring Park—a site surrounding the previously constructed circular Dishui Lake [pictured above]. The Green Ring Park plays a critical role in the health of the local ecosystem and the economic value of Lingang’s urban districts. The design of the park had to start from a much broader context—one that included the environmental and social issues facing Lingang—and treat the park as a catalyst for the holistic improvement of this reclaimed land.

The current conditions of the site show several issues resulting from land reclamation and the master plan for the new city. Soil salinity and habitat loss rendered the landscape barren. The sprawling master plan exacerbated these problems. The windy site makes it hard for plants or people to live. These conditions conspired to impede the population growth and economic development of this new city.

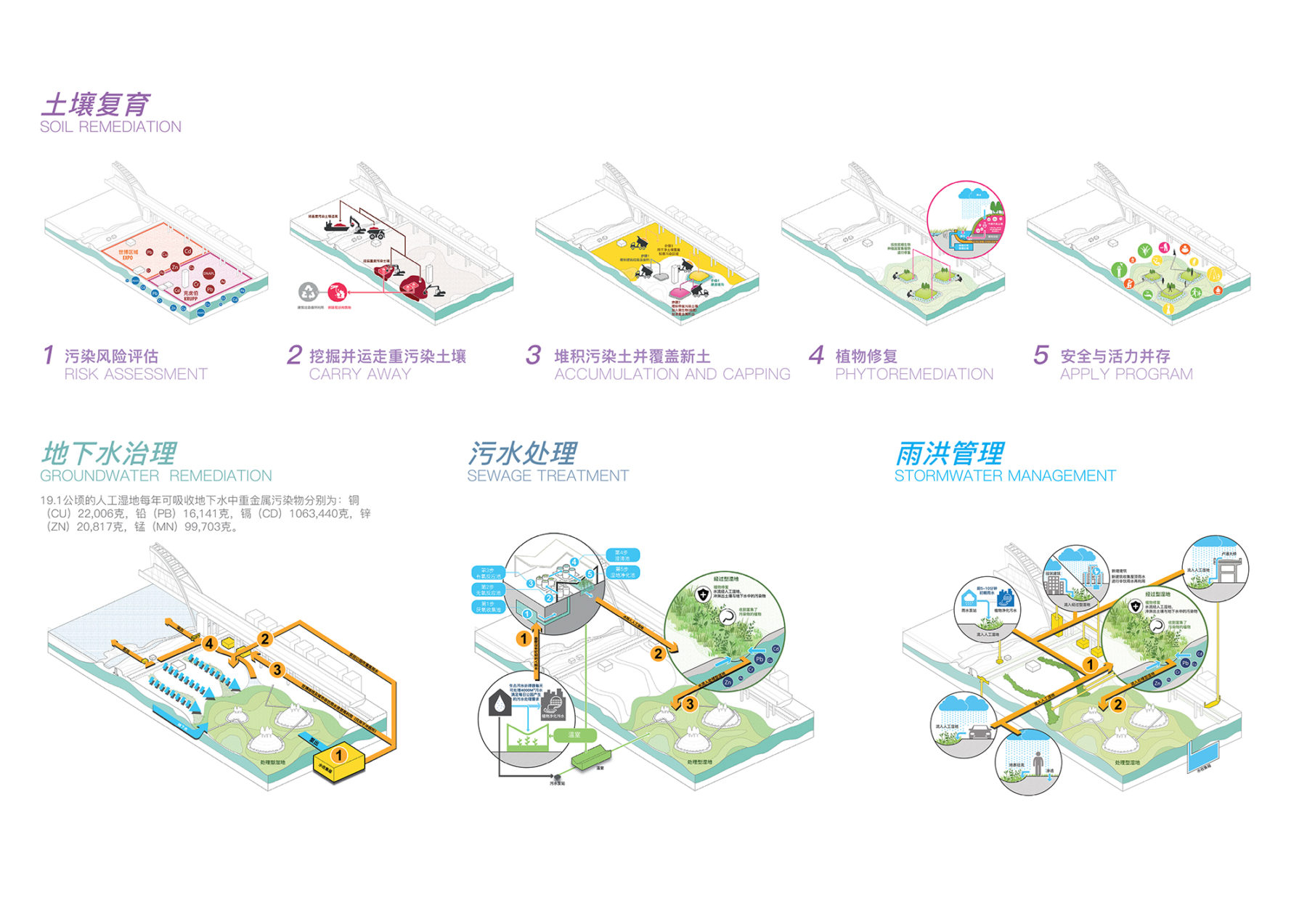

In our design submission, we offered several strategies to begin remediating these issues, including: building coastal protection systems and remediating saline soil; creating a complete ecological network; remediating stormwater; harvesting wind energy for power and recreational purposes while also building wind protection barriers. In addition to these environmental improvements, we also called for the creation of several destinations to serve local residents and visitors to contribute to the overall livability of Lingang.

Our ultimate goal was to make the park a welcoming place for both people and wildlife. The design strategies are geared toward long-term success of the site, as well as the city, by accelerating its succession to mature plant life and restoring the coastal habitats along the shoreline. Staggered stages of succession at different segments of the park will result in a very diverse landscape, with forest, tree groves, gardens, lawn, thickets, meadows, agriculture fields, wetlands, and water bodies distributed across the site. This diversity enriches the habitat value and user experience of the entire city. As the physical environment constantly improves, more people will be willing to live and work in Lingang New City.

With tighter control from the central government on the limited agricultural land in the country, and already oversized development in the metropolitan area, Shanghai has started to look at existing developed areas for growth opportunities. As a result, urban regeneration has gained more and more attention in the city, both inland and along the rivers. As is the case in other cities around the world, urban regeneration projects require careful navigation of current needs, historic preservation, existing infrastructure, and political issues. Strong design integration at each juncture is crucial to the success of these projects.

Like other waterfront cities around the world, Shanghai’s waterfront had long been the city’s vibrant center—specifically dominated by industrial uses and ports until the last few decades when those industries began to move away. Now, commercial and residential development, as well as recreational programs, are gradually bringing life back to the waterfront.

An example of such waterfront district rejuvenation is the Xuhui Riverfront Area, which has transformed from an airport and industrial base into a high-end office and commercial development cluster and popular public destination. As part of this transformation, Sasaki was engaged to design the landscape for the nine-hectare Xuhui Runway Park inlaid among high-density developments. The design adapts a historic runway into a public green space for recreation and peaceful respite from the surrounding city.

Despite all efforts made in revitalizing city’s waterfronts, the qualities of many riverfront parks are still not complementing Shanghai’s growing status as an international city. Decades of heavy industry and agricultural practice in the upstream had severely diminished the ecological health of Shanghai’s Huangpu River.

At the same time, the river was disconnected from the city’s population—a social and recreational amenity so close, yet mostly out of sight and out of reach. Among all riverfront parks along Huangpu River, only a few addressed the water quality issue or habitat value, fewer provided improvement on the connections between city and river, and many are not popular due to lack of program or proximity to users. Some park designs are still following the simplistic panacea of planting more trees. With Shanghai’s goal of becoming a remarkable global city, the redesign of its waterfront, the city’s frontage, requires a much higher level of comprehensive thinking.

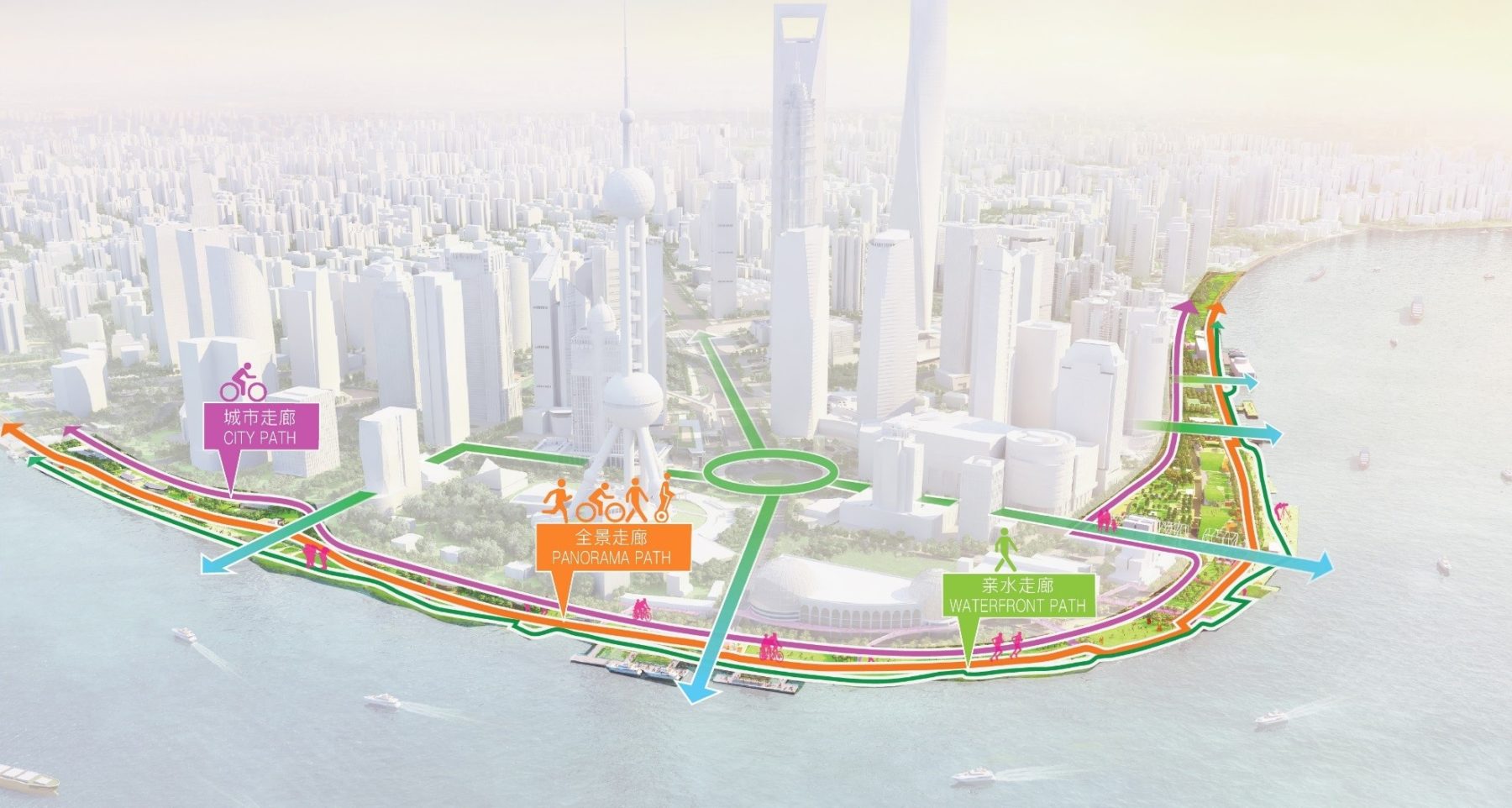

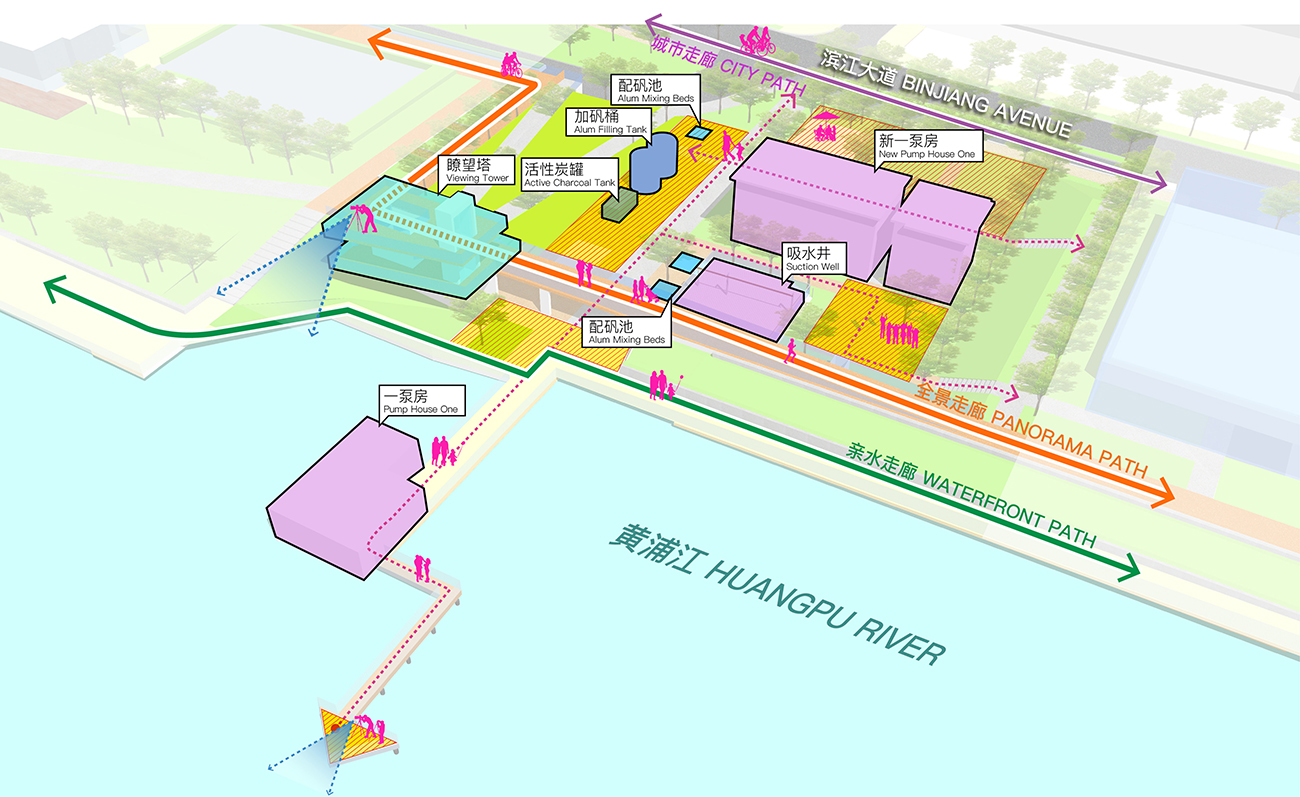

As a new chapter of the effort to improve the waterfront, the Huangpu Riverfront Greenway project set out to link all existing waterfront areas into a continuous system. With a design scheme dubbed “Reunion of the City and the River,” Sasaki’s plan for the 2.5 km (1.56 mi) long Lujiazui riverfront not only creates continuous pathways along the river, but more importantly, addresses larger issues in the waterfront city. These issues included returning the riverfront to public use, injecting more energy into the inland parcels, restoring its ecological functions, celebrating its cultural heritage, and creating a central public space in Shanghai’s most prominent locations. We envisioned the site as a catalyst for high-quality urban life.

During the design process, we interviewed many park users and stakeholders of the site and surrounding developments; surveyed site foot traffic at peak and off-peak hours; and made multiple presentations to the clients, stakeholders, and various government agencies in order to produce a visionary yet pragmatic plan to improve the quality of this central public open space.

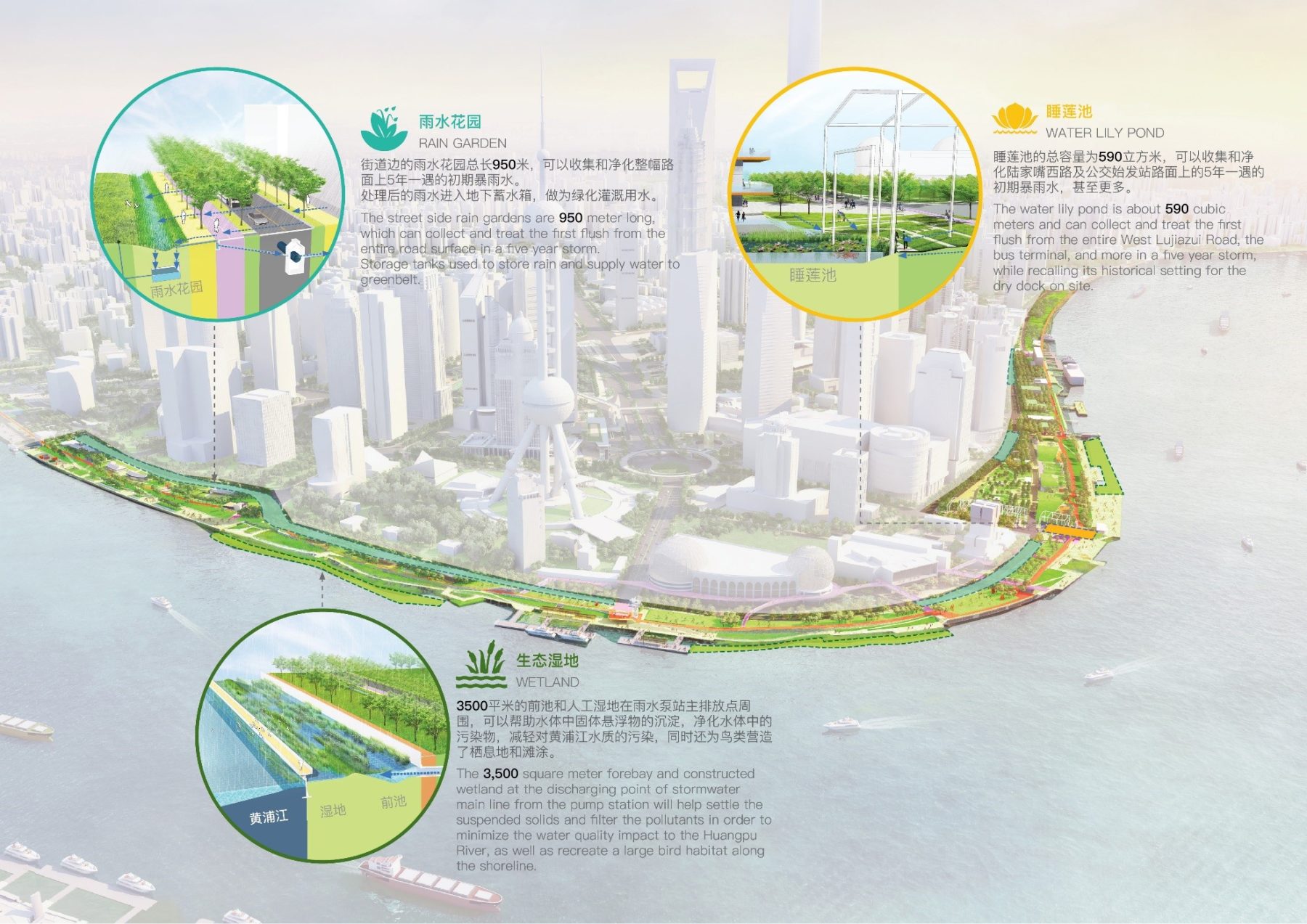

The holistic design strategy for the riverfront comprises a spatial framework of three paths stretching along the river, while eleven gateways and viewing corridors link the city back to the river. The river’s history as a vital industrial corridor is celebrated by preserving and restoring selected artifacts near the waterfront. The plan’s ecological design strategy integrates existing site conditions with future uses and its historic context. A comprehensive stormwater management system integrated with riverbank enhancement measures will improve water quality and restore habitats along the shoreline while drawing more people to the riverfront. Assisted by native plant species and diverse landscape types, the plan will promote a sustainable and local landscape for the Yangtze River Delta and complement the overall design.

Shanghai’s 2035 Master Plan, approved in the spring of 2017, sets up goals for Shanghai to become a standout global city; one of creativity, humanity, and resiliency. The plan reflects the city’s forward-thinking culture and calls for bold exploration of creative approaches to creating high quality places. Large public green spaces will play a critical role in achieving such a grand vision, providing potential for sizeable impact on the local ecology, its public attributes, and flexibility.Sasaki’s design scheme for the 189-hectare Shanghai EXPO Cultural Park was an exploration of how large public green spaces can contribute to a reputable global city in the making. One of the two finalists in an international design competition, Sasaki’s proposed park celebrates the unique ecological, cultural, and innovative contexts of this largest riverfront green space in the city center that will create a unique destination—a gift for the people of Shanghai to enjoy.

As a visual focal point from the west bank of the Huangpu River, this land in the Pudong District has evolved over the decades: from natural wetland, to farmland with an expansive canal system, to a base for heavy industry. The opening of the 2010 Shanghai EXPO represented yet another new chapter of the site’s history and symbolized the beginning of the site’s post-industrial rebirth.

Our park design is aligned along an ecological spine that connects the Huangpu River with the open space corridor to the east. The landscape framework for the park then builds upon this spine, linking the riverfront and the city, as well as the east and west banks of the Huangpu River’s vernacular features, which interprets the varied history of the site.

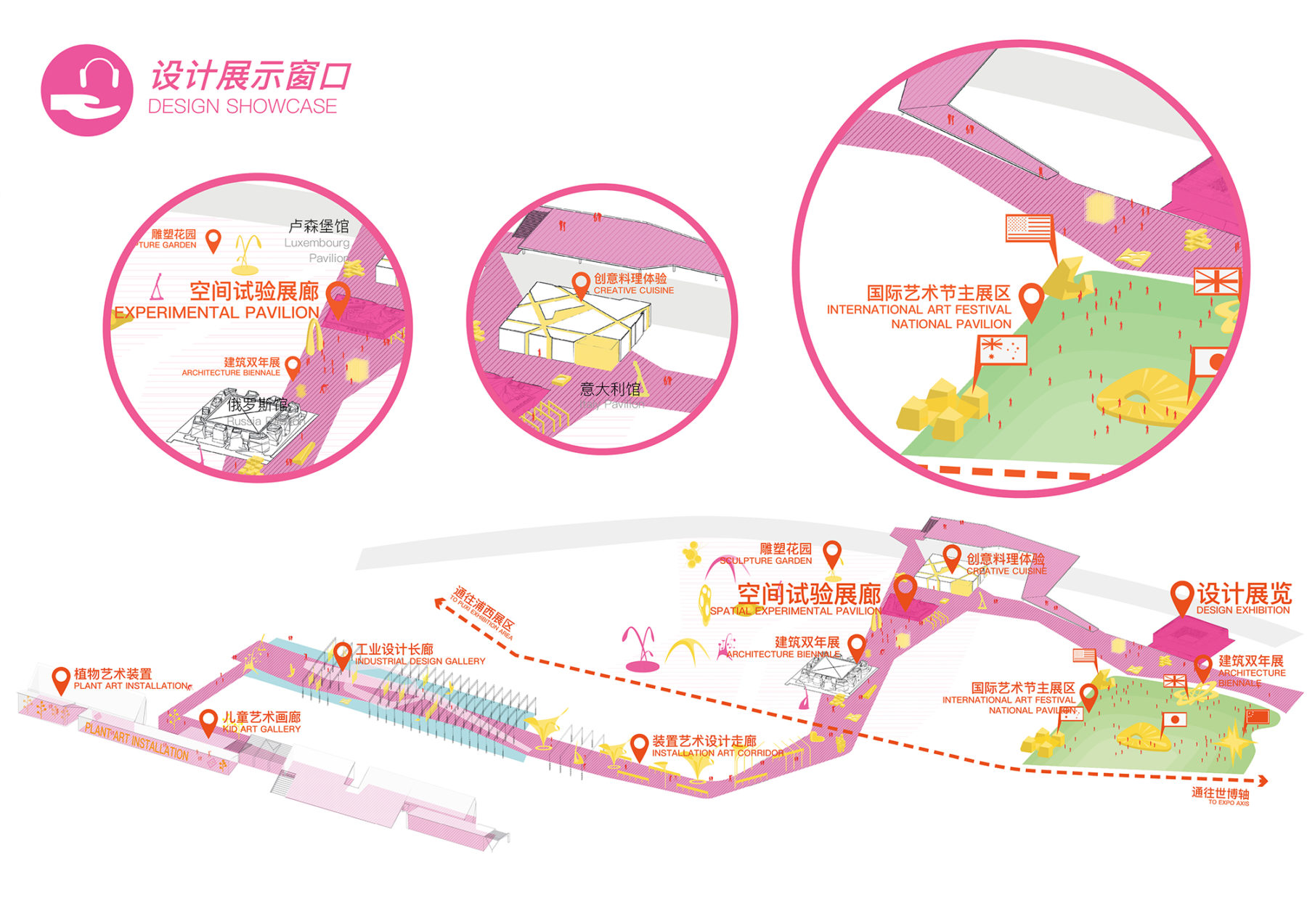

The top priority of our design was to create a test bed for green infrastructure and technology to remediate the site, which had been polluted by its past industrial uses. Embracing the EXPO’s slogan, “better city, better life,” the design aims to create a new identity for the site that represents the urban-cultural life of present-day Shanghai: as an arts and culture destination on the Huangpu River. As another expression of the EXPO spirit, the park is also designed to be the window to the latest innovative ideas. The “Inspiration Corridor” essentially transforms the entire park into a stage [pictured below].

Across the globe, the value of large public urban green spaces is clear. These spaces have major impacts on the local ecology and residents’ quality of life. Well-designed spaces can enhance the ecological value, create recreational and educational destinations, and promote local culture. With so much riding on these critical elements of the urban experience, who should be responsible for making decisions on the future of such public green spaces?

As the ultimate users of the spaces, the local public plays a very important role in the success of such spaces. In Western countries, holding public meetings during the design process is a common way to involve the public as well as to engage stakeholders whose support could greatly expedite the project. It also ensures that taxpayers have input on how their tax dollars are spent.

Too often, the decision-making process on Chinese landscape projects is shrouded and unclear. As many in China become increasingly aware of the ecological cost of the country’s recent decades of economic vitality, pressure for expanded transparency and public involvement is growing. This shift in public knowledge and perception represents a great opportunity. When designing public spaces, the outcome is more likely to be successful if the public for whom the space is designed feels that they have been heard. Tensions and controversy arise when the design process is approached in a didactic, rather than symbiotic, method.

In the face of continued growth and development, Shanghai still has a way to go when it comes to implementing landscape projects that provide healthy environments for humans, plants, and wildlife. As Shanghai continues to grow into its role as a leading global city, we hope that the quality and intentionality of its large public green spaces will begin to catch up with its continually booming economic development.