Zidell Yards: Expanding Portland’s Public Waterfront

Revitalizing one of the last undeveloped sites along the Willamette River to return it to Portland's public

Sasaki

Sasaki

The history of Suzhou Creek is integral to the story of Shanghai—and its transformation from a modest fishing village to the cosmopolitan financial hub it is today.

As a crucial transit route and productive industrial waterway, Suzhou Creek helped power the city’s development through the 20th century, as Shanghai’s iconic skyline rose quickly around it. However, as the city was rapidly developing, the industrial activities along Suzhou Creek contributed to rampant pollution and degradation of the vital waterway.

Suzhou Creek has long been synonymous with pollution and neglect in Shanghai’s cultural memory. Indeed, the urban districts that grew around Suzhou Creek—the wealthy Jing’an neighborhood to the south and the working-class Zhabei neighborhood to the north—were developed facing away from the waterfront. But beginning in the 1990s, Shanghai began a massive clean-up effort funded by grants from the Asian Development Bank to give Suzhou Creek a second life worthy of its illustrious history. Simultaneously, the unification of the Jing’an and Zhabei districts into a jurisdiction that encompasses Suzhou Creek at the center, set the stage for the river to become the heart of a new urban district.

Suzhou Creek’s transformation over time

With measurable improvements to the water quality of Suzhou Creek, Shanghai authorities hosted an international design competition in 2016, seeking bold ideas for a complete revitalization of its 12.5 linear kilometer waterfront. What began as a competition seeking strategies for rethinking the river’s immediate edge conditions evolved into a design challenge that thought more broadly about the creek’s significance and impact on the evolving city.

Sasaki won the competition with an ambitious plan that envisions Suzhou Creek as a gathering place for humanity, overcoming its past perception as a physical and psychological divide interrupting the city’s fabric and separating social classes. By creating a network of experiences throughout the city that tie to the waterfront, an entirely new district emerges, reconnecting neighborhoods and restoring the waterway as a public resource.

Recognizing the opportunity to unleash Suzhou Creek’s potential as the identity of this newly combined district, Sasaki recommended expanding the perceived waterfront of Shanghai into the urban blocks adjacent to the creek. Today, a chaotic landscape of factories, docks, and a concrete floodwall makes it almost impossible to reach the river on foot. Similarly, views to the river are blocked by existing and often unregulated development.

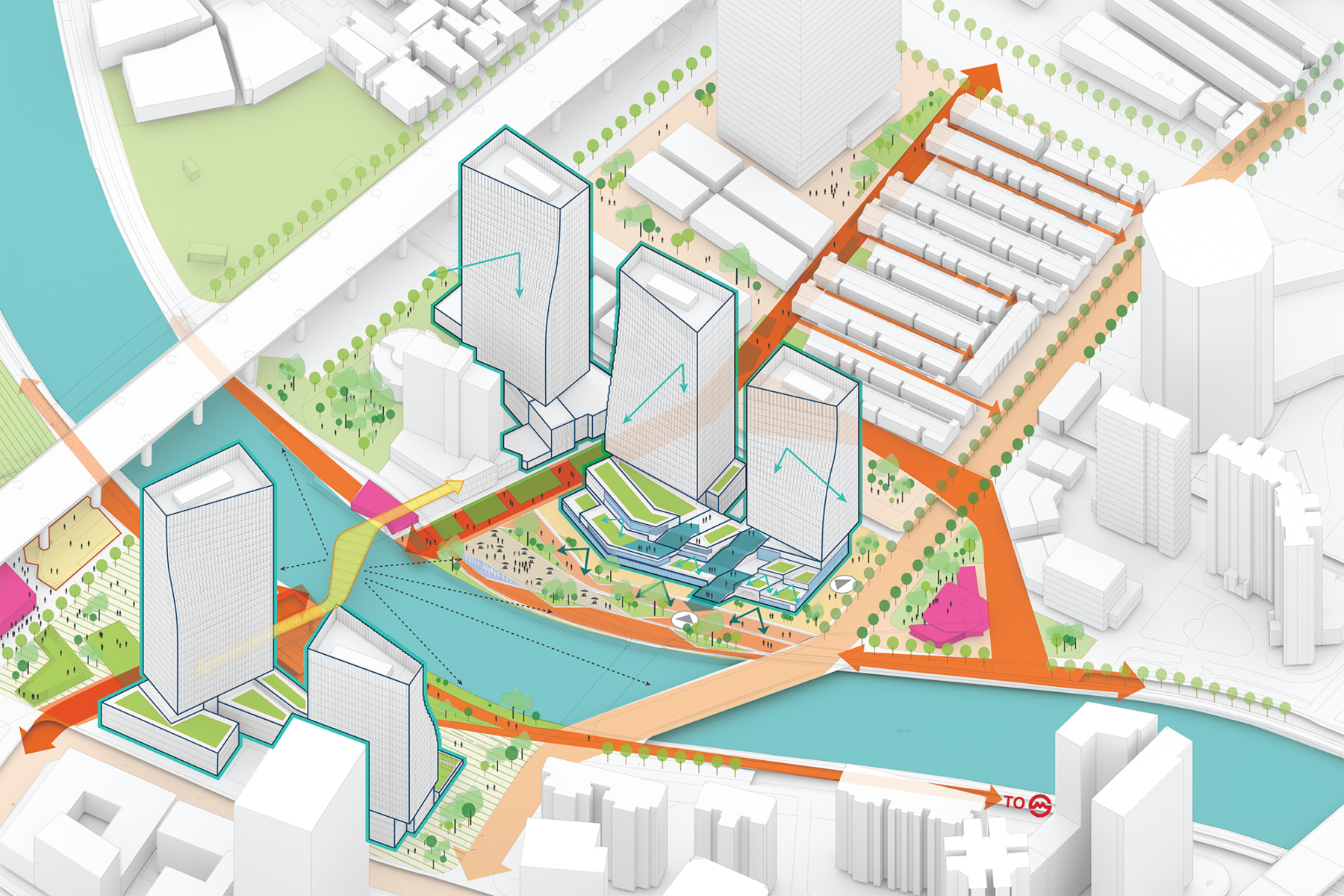

To overcome this, Sasaki’s urban design strategy centered on the concept “push, pull, bridge, and extend” to re-stitch the city fabric on either side of Suzhou Creek. By “pushing” into adjacent neighborhoods, an extension of the creek’s linear landscape provides more open space for public use and acts as a connective tissue to bring people to the water. “Pulling” both existing and new commercial and cultural uses towards the waterfront promotes activities leading to the water’s edge and enhances the sense of orientation to the creek. “Bridging” over the creek encourages pedestrian flows between public spaces on both sides of the river, and overcomes the existing physical barriers between districts. Finally, by “extending” the public realm along Suzhou Creek further into adjacent city blocks, the energy of the waterfront radiates beyond the banks of the creek into the city as a whole.

The Suzhou Creek plan fosters connectivity, extending the public realm throughout the district

By expanding public spaces around the river, giving reprieve to the area’s high density development, Sasaki’s plan creates a more cohesive pedestrian experience along the waterfront—one that is anchored by key public spaces throughout. New pocket parks alongside the creek and within existing neighborhoods are spaced no more than 500 meters apart, responding to the city’s long-held desire for more vibrant, community-oriented open spaces, and creating inviting portals to the banks of the creek.

Vibrant public spaces allow people on both sides of Suzhou Creek to enjoy the waterfront and the city

Sasaki’s plan also strengthens connections between underserved communities and inaccessible locations. With its proximity to the Shanghai Central Train Station and five subway lines, the creek will be a connective corridor, providing a critical pedestrian link from an array of neighborhoods to a transport hub. Isolated neighborhoods are energized by new mixed-use development and strengthened connections to nearby destinations, such as Shanghai’s Central Train Station and the popular M50 Arts District.

Although the plan charts a new path forward for Suzhou Creek, it also celebrates a shared history of the city that is integral to Shanghai’s contemporary identity. Within the neighborhoods surrounding Suzhou Creek, the plan preserves Shanghai’s unique vernacular architecture and intricate pedestrian networks with minimal, strategic interventions that transforms them into new mixed-use destinations while retaining their existing character. Historic warehouses along the creek such as the Fuxin Flour Mill and the Sihang Warehouse are repurposed as cultural destinations to further strengthen the area’s burgeoning arts scene.

New development is set back from the river so that the public can engage directly with the water

Referencing Suzhou Creek’s historical importance as a transportation corridor which moved goods through the city, the contemporary vision for the creek envisions it as a landscape for conveying people, allowing them to experience Shanghai from a unique perspective. Similar to other works of modern landscape architecture such as New York’s High Line and the Chicago Riverwalk, Suzhou Creek presents an opportunity to transform the industrial past of the system into a place to commune with neighbors, the natural environment, and the vibrant city fabric.

Waterfront development in places as distinct as Zidell Yardsin Portland, Oregon; Las Salinas in Viña del Mar, Chile; and Suzhou Creek in Shanghai, China reveal that no matter the geography, waterfront transformation manifests far more than physical changes to a site: thoughtful, cohesive waterfront design imbues these places with new identity and the power to shift the entire experience of a city. The success of an industrial waterfront reimagined and re-oriented for community enjoyment is dependent upon its ability to tap into that universal human desire to get close to water—cultivating conditions that ensure access, safety, vitality, and beauty. When accomplished, we restore the importance and usability of water as an asset, honoring the legacy of past uses while ushering in the next era for both these timeless bodies of water and the dynamic communities that inhabit their shores.

This is the last piece in our series about the draw of urban waterfronts across the globe. Read more pieces in the series about Portland’s Zidell Yards and Las Salinas in Viña del Mar, Chile.