The Frederick Gunn School Tisch Center for Innovation and Active Citizenship

Washington, CT

Sasaki

Sasaki

From integrating architecture and urban design to collaborating with users of all ages, Marta shares her process of shaping spaces that balance context, innovation, and community needs.

Designing buildings is a practice of discovery. It is the challenges that arise during the process that energize and inspire associate principal and designer Marta Guerra-Pastrián. Unafraid of questioning or uncertainty, Marta embraces design that takes shape through collaboration and experimentation.

Trained in Madrid and New York, Marta utilizes her broad expertise in both architecture and urban design to think across scales and contexts. At Sasaki, her projects for higher education, independent schools, and cultural institutions are characterized by a commitment to listening to clients and communities. For Marta, the “magic” of the designer lies in synthesizing complexity into clear, communicable ideas – ultimately helping people connect with spaces and empowering them to welcome others into these shared environments.

In Spain, where I come from, you actually need to decide whether you want to become an architect when you’re 18. I didn’t know anything about the profession, but I was good at drawing. I found architecture to be incredibly compelling in my formative years. The school I went to (Polytechnic School of Architecture in Madrid) trains us heavily on the technical side, and at the end of your thesis you become a licensed architect.

I always wanted to study abroad. After working a few years in Spain, I got a scholarship through Caja Madrid Foundation, and they fully sponsored my studies for a post-professional master in urban design at Columbia University in New York. Going there expanded my understanding of architecture for me. It helped me frame it within a larger context—the site, social and economic context, and how we understand our place in communities. It gave me a lot more than purely the technical act of making a building. That experience was eye-opening.

I was originally going to come to the United States for a year and then return to Spain. But it was 2009, and as many may have related to, with the recession there were no jobs anywhere. I was lucky that my scholarship was extended for another year to complement my studies with a research program. I stayed in New York and worked a couple of months for a media company until I moved to Boston.

I enjoy urban design in a research capacity but maybe less as a practice itself. I use my urban design knowledge on typologies and place creation to inform architectural concepts within a larger context of geographic, economic, financial, and social background.

However, I don’t think I will ever be able to erase architecture from my core background. I think of the architectural space first and foremost, and then how that space is shaped within all these other contexts. My urban design background helps me ground the ideas around placemaking more fully.

I feel like I have been meandering without a very structured path in my career. I took advantage of some opportunities that came up, and those have helped me define the way I look at things. I evolved through these experiences. Maybe this is why, in a way, what I like about the work I do at Sasaki is that projects tend to also emerge from this process of discovery. Usually my role is less about fitting a given program into a site, but more about unveiling the building needs out of a process of planning, or programming, based on visionary ideas for what a campus, an institution, or a city want to become. Being able to join those very early conversations, driving the ideas through imagining how buildings are shaped, and then letting the vision travel through the details, can lead to surprising results.

Running out of ideas is not a point of tension for me. The question to me is: How do we sift between options, and what are the best ones? I love not knowing what the best ideas are going to be in the beginning; as the process unfolds, they may come from unexpected places and people. I try to keep an open mind about what the discovery path will be. I think that is very exciting here at Sasaki because of the diversity of the work we do.

A lot of people say that architects are problem solvers… I personally think of myself as a problem maker! We create things that do not exist based on imagination, and that act of invention involves a lot of complexity that we then need to shape into architecture. To me, setting this problem is very exciting.

We typically start by compiling and analyzing information from the site, from the research of its context; we also hear from the community, the client, and the end users. These groups usually have conflicting priorities. There is that moment when we are able to synthesize all that work into a few preferred concepts that are able to speak to everyone–that is kind of magic. When we do that, people are amazed by how we can get all these layers of information and turn them into something that they can understand and relate to.

Getting that momentum of endorsement is super powerful because then the design is able to start having a life of its own and creates an amplifying ripple effect. For example, the other day I heard Carole Charnow, President of the Boston Children’s Museum, present our project to the Green Ribbon Commission. She communicated the ideas we’ve worked through together to a large audience in such a compelling and inspiring way.

When we’ve been able to express those concepts in a way that clients, users, and other designers understand, it creates this sense of ownership in others. That is something that is very unique to our profession.

The design process may surface many ideas but maybe none of them holds yet the potential for the best impact. I believe that the iterative process in which many people, and especially diverse mindsets, are around the table working together leads to something better. I try to instigate this work in teams, where we collectively and iteratively review the project, because then we can simultaneously hold the big picture that I’m able to bring to the group, but also the details that my peers can capture, yet I would not be able to remember by myself. We complement each other.

Working with the planners at Sasaki is always a learning experience for me. I admire their ability to collect and absorb incredible amounts of information, and then summarize it in a few bullet points, synthesizing the complexity into succinct concepts. As designers, we work similarly, integrating all these layers of information and shaping them into a clear spatial intent, by listening a lot, and by iterating again and again, in constant search for a better, cleaner and simpler resolution. Design is an inherently optimistic practice.

In the past we would sketch on trace paper, scan it and draw on top of it on the computer, print, and repeat. Now we sketch and iterate directly on programs like Miro.

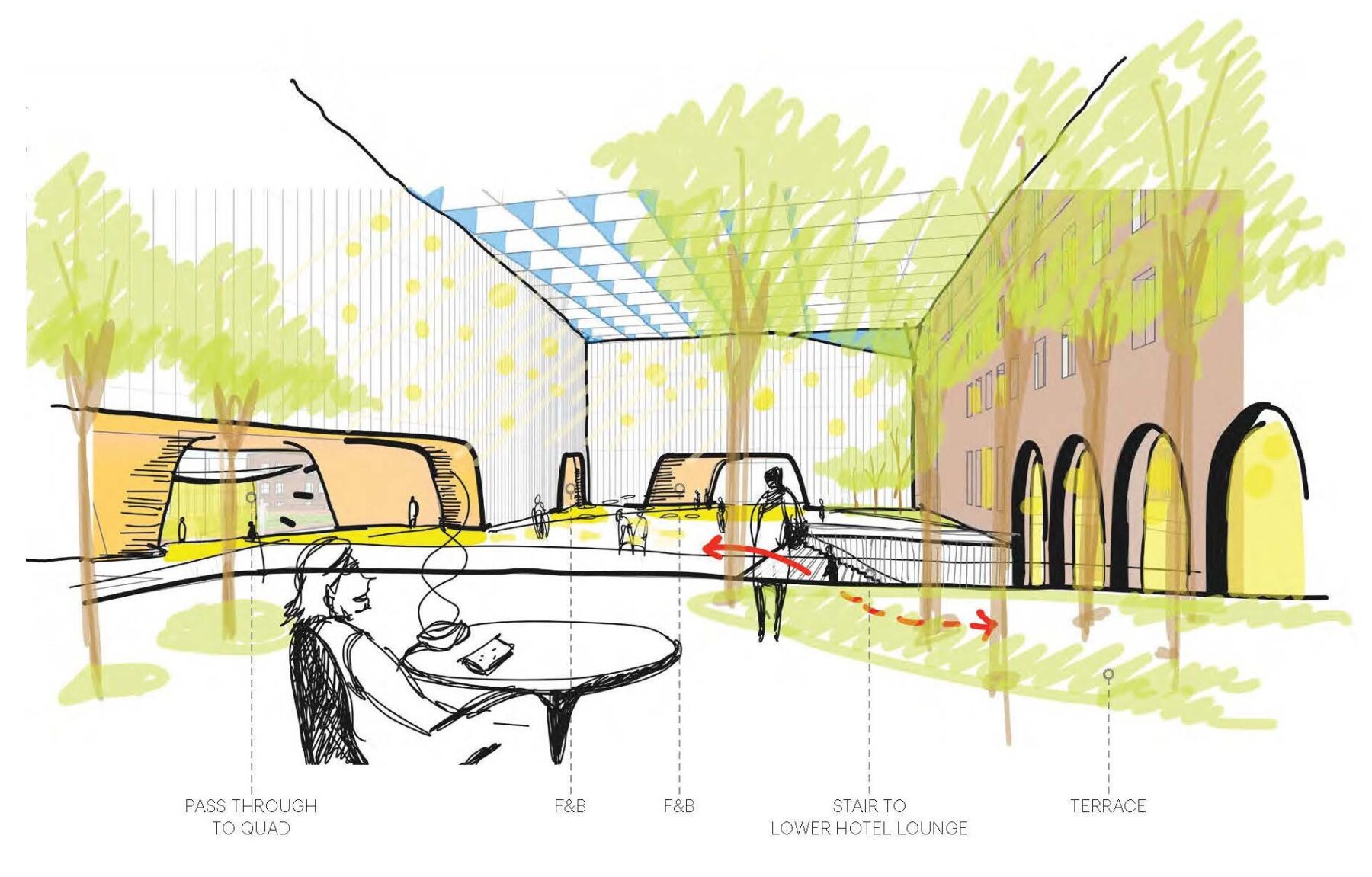

I love sketching because it is loose, but it’s also crisp enough to illustrate an idea and move forward. Even if it’s very abstract, I find sketching to be a really good tool for myself, of course, but also for others to reconstruct the missing parts of the sketch and imagine what they want.

I tend to use it less to describe an object, but to convey a concept or a feeling. Rather than constantly trying to have polished drawings for iterations, or progress presentations, I prefer to use sketches to have a client imagine: What it can feel like to have a coffee waiting for your friend, being in that space? Or seeing a building shine through and the program on the ground floor spill out to the street? I aspire to spark the imagination of others. In turn, people can develop a deeper connection to our design, because we are making them participants of that collective imaginarium.

I think for me, the project that is closest to my heart is the Lawrenceville School Gruss Center for Art and Design (GCAD). It had the right amount of uncertainty to be something that no one was expecting because the context is quite traditional. Coming to a consensus about creating a glass open space in the middle of the campus was the right push for the school to move into the next evolution of buildings and helped them to think progressively about their campus.

It was very uplifting for me to work with teenagers as a user group. Their stresses from exposure to social media are very different to my own teenage years, but they still have the same concerns that we had: Where are we going to hang out? Can you show me the sofa where I’m going to sit? Can we select the finishes and the furniture? They’re always looking for places to be together and socialize, and of course they have to study and we have to provide all those academic spaces—but that kind of malleable space, they really want to own it.

At the GCAD we designed prescribed spaces, but also many informal spaces where students can hang out, and find more intimate nooks for one self, or for a small group of people. I learned so much from that project and from that process, not just from the client and the faculty that informed the decisions, but from the way young adults were taking over the space—I thought that was very inspiring.

When we think of the younger generation and all the pressures that these kids go through today—how can a space help release some of it? Planning for an array of experiences, bringing natural light to every corner, creating beautiful spaces they want to take care of. GCAD was a clear experience for me in understanding the very direct interaction between the space we are designing, and who’s going to use it.

I’m currently working on a few projects where I’m helping craft the next steps for campuses and institutions.

For the Boston Children’s Museum, we are looking at the critical renovations that need to happen to fortify the building against sea level rise, but we are also using this to maximize the opportunities out of the problem: Can we design for outdoor activities while strengthening the connections to the inside? Can we find small expansions in the footprint and access the amazing views from their roof? Designing in an area that is vulnerable to flooding while updating the building and site to create more learning opportunities for children and families, makes the Museum not only more relevant, but also their mission meaningful and long-lasting.

We are taking a similar approach for the Lincoln Beach Redevelopment Plan. Behind the idea of making the beach accessible lies the plan to heal from its past, and design a resilient and inclusive place. In this case, we have worked relentlessly with the City of New Orleans and a very active community to distill the best programs for the beach. It will soon be moving into the next phase towards implementation.

Another local project I am working on is the Master Plan for the Berklee College of Music in Boston. We are looking at what the next 20 or 30 years can look like for them, with the ambition of updating their campus towards economical, social, and physical resiliency.

In all the conversations, there is so much talk about the future. I very much enjoy the process of envisioning for future generations. Ultimately, our role is to create beautiful and inspiring places for them.