Suzhou Creek

Shanghai, China

Sasaki

Sasaki

The City of Wuhan is re-envisioning one of the world’s largest riverfront parks to embrace flooding as an essential dynamic of the public realm

The Yangtze is Asia’s longest river and drains one-fifth of China’s land area. Revered as the “mother river,” it has nurtured China’s history, culture, and economy since the dawn of civilization. This relationship between the people and the river has, in recent years, grown tense. Despite unprecedented advancements in engineering, all major cities on the Yangtze increasingly suffer from mounting flooding damage—demonstrating that the river is far from tamable.

Emerging because of its relationship with the Yangtze, central China’s largest city of Wuhan has coevolved with the river so symbiotically for the past 1,800 years that every milestone in its history has been tied to the river. Centuries of floods created fertile land for the early settlers, and high water safeguarded the birth of the city. As Wuhan has emerged as one of China’s hotbeds for technology, education, and innovation, land prices have soared and the city faces rising conflicts between development pressures and public demand for open space. It is striving to explore new ways of embracing the river after nearly a century of industrial exploitations and urban expansion.

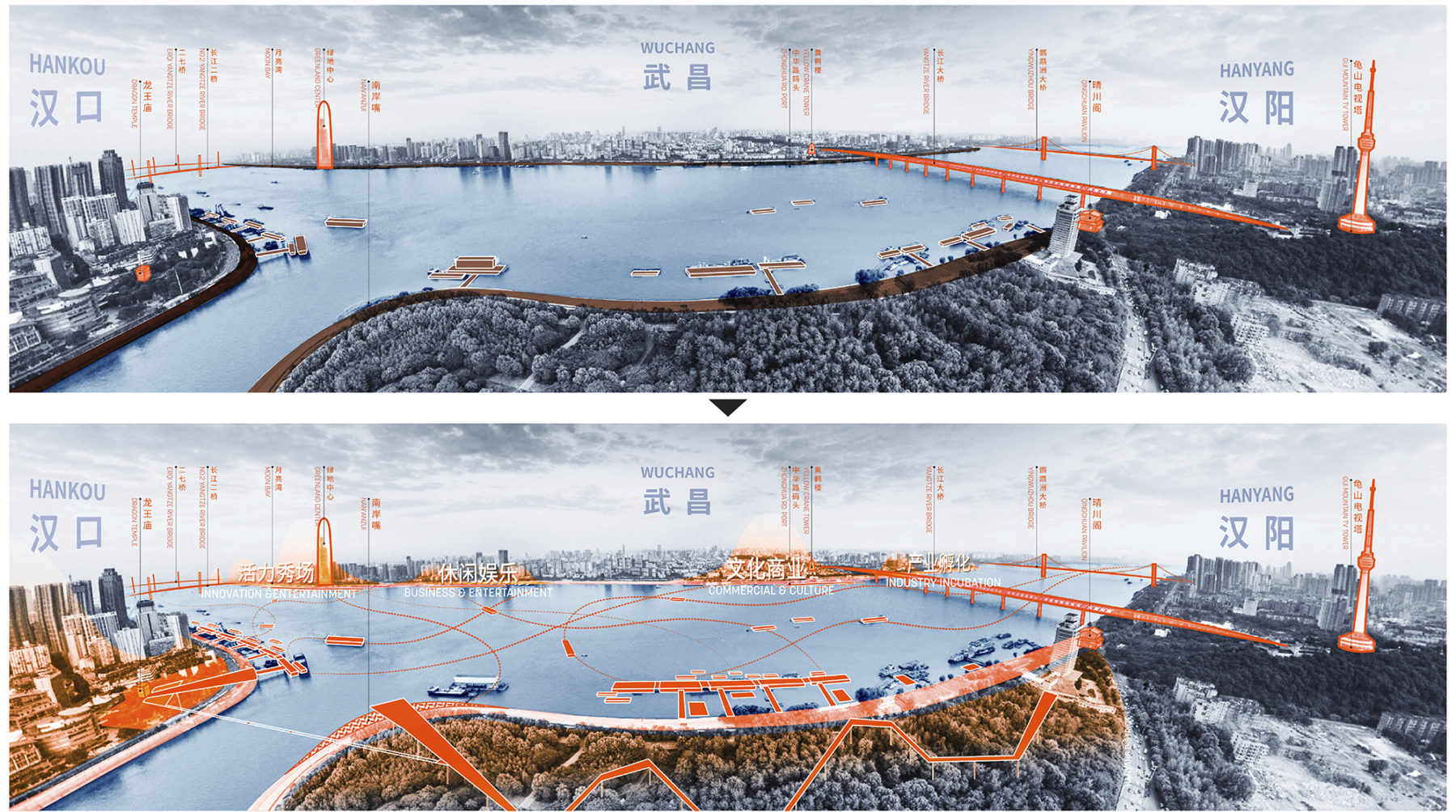

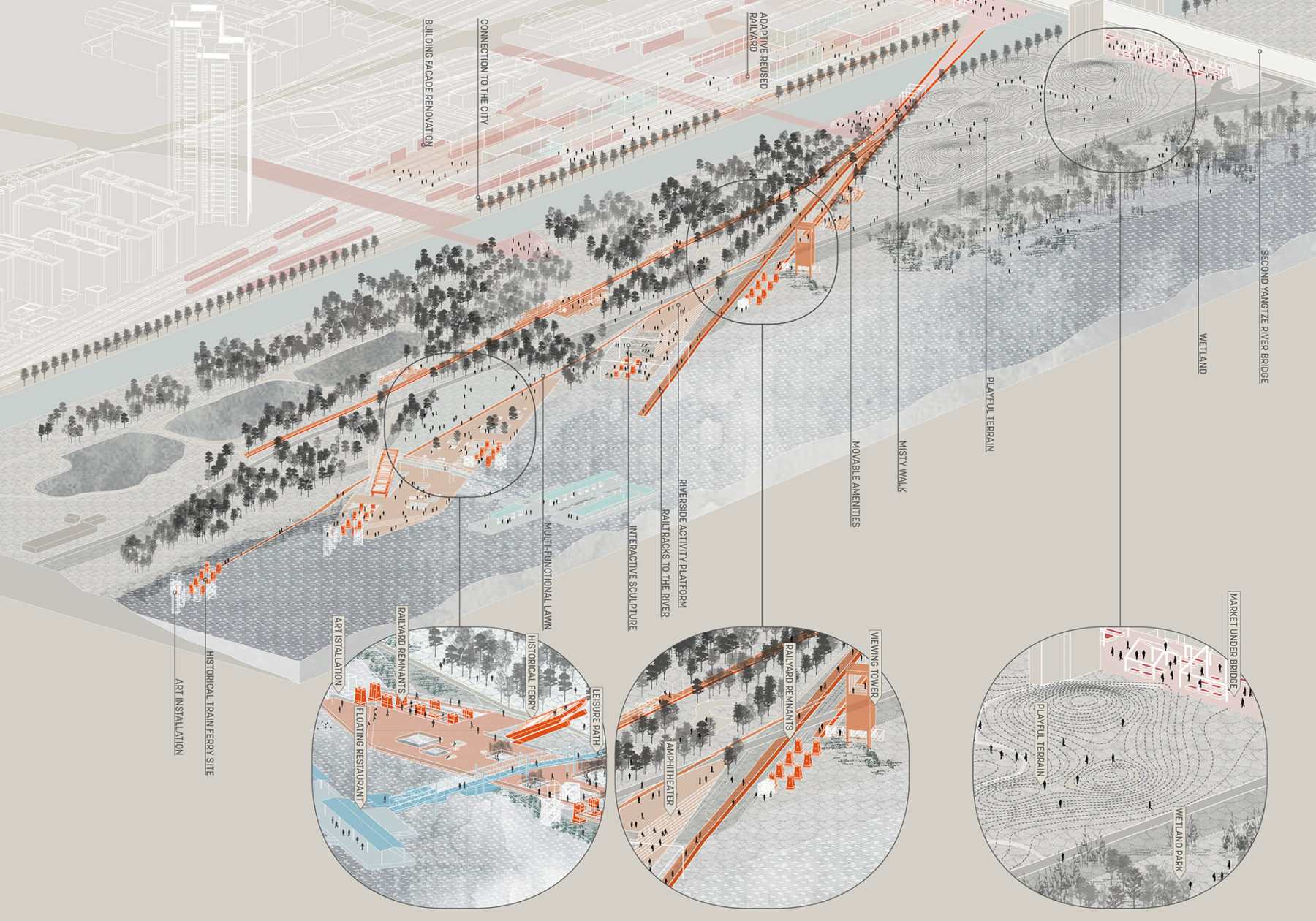

Wuhan’s Yangtze Riverfront Park leverages the river’s dynamic flooding to nurture a rich regional ecology, reinforce traditional wisdom and the local identity of living with an ever-changing river, and creates a dynamic recreational experience which is acutely attuned to the seasonal rise and fall of the Yangtze’s waters.

The Yangzte Riverfront is an integral part of Wuhan’s open space network, and is designed to celebrate the river’s spontaneity

The reimagined vision for the park reunites the river with the city and its people

Plan for the Yangtze Riverfront Park site

This “river culture” is so deeply embedded in Wuhan that today people still frequent the riverfront parks even when they are flooded—enjoying the rare excitement of such intimate contact with the water. The design of the park celebrates this strong river culture and leverages frequent flooding events as a vital driver of placemaking strategies. Much of the programming along the river is designed to celebrate the river’s spontaneity and incorporate its flooding as an essential element of the ever-changing landscape.

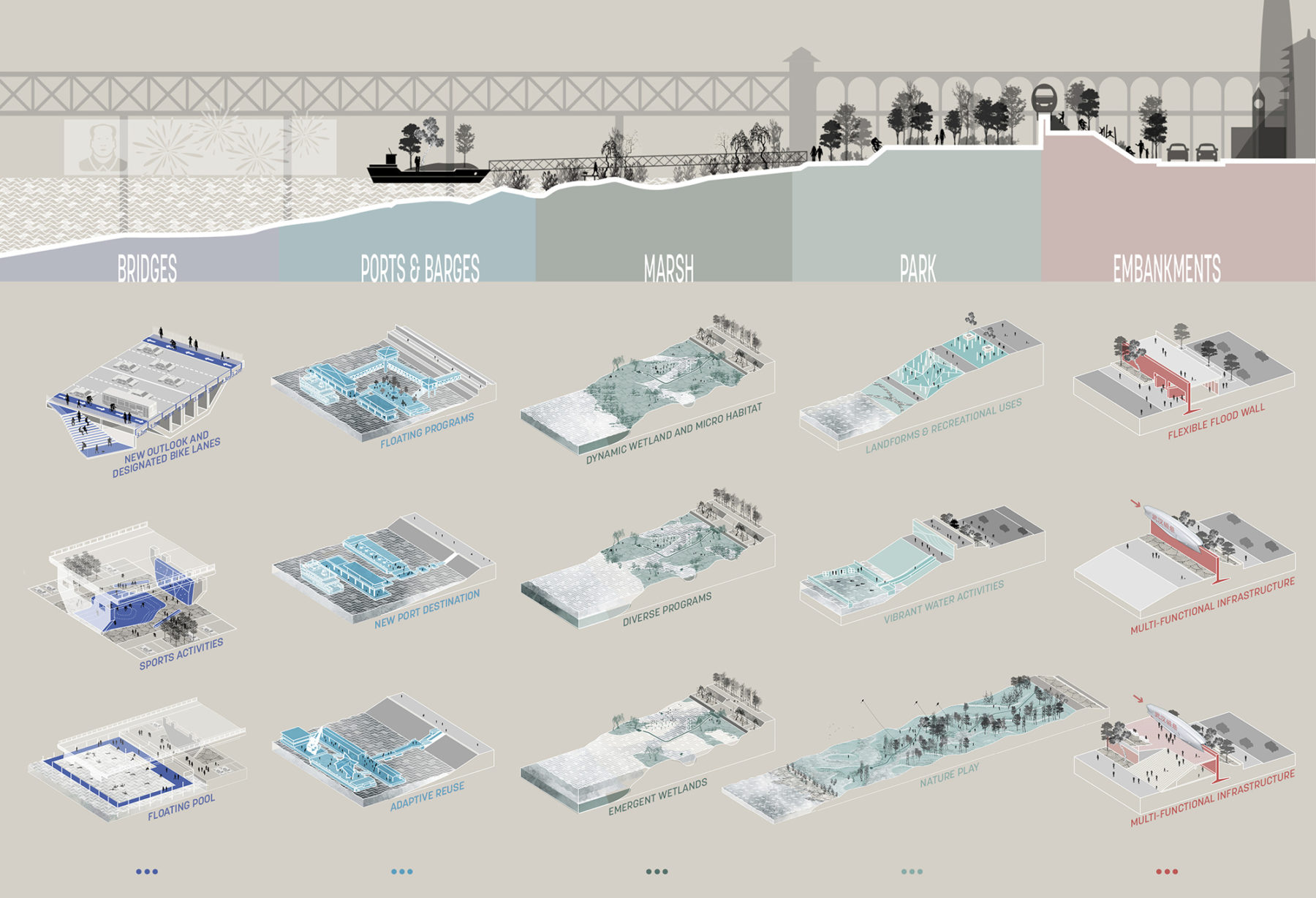

Comprehensive toolkits provide flexible solutions to the riverfront’s various conditions and complex challenges

The decommissioned freight train ferry terminal is an example of adaptive reuse which offers new experiences while referencing the industrial legacy of the waterfront

The vibrant morning market at Sanyang plaza celebrates the diversity of its surrounding neighborhoods

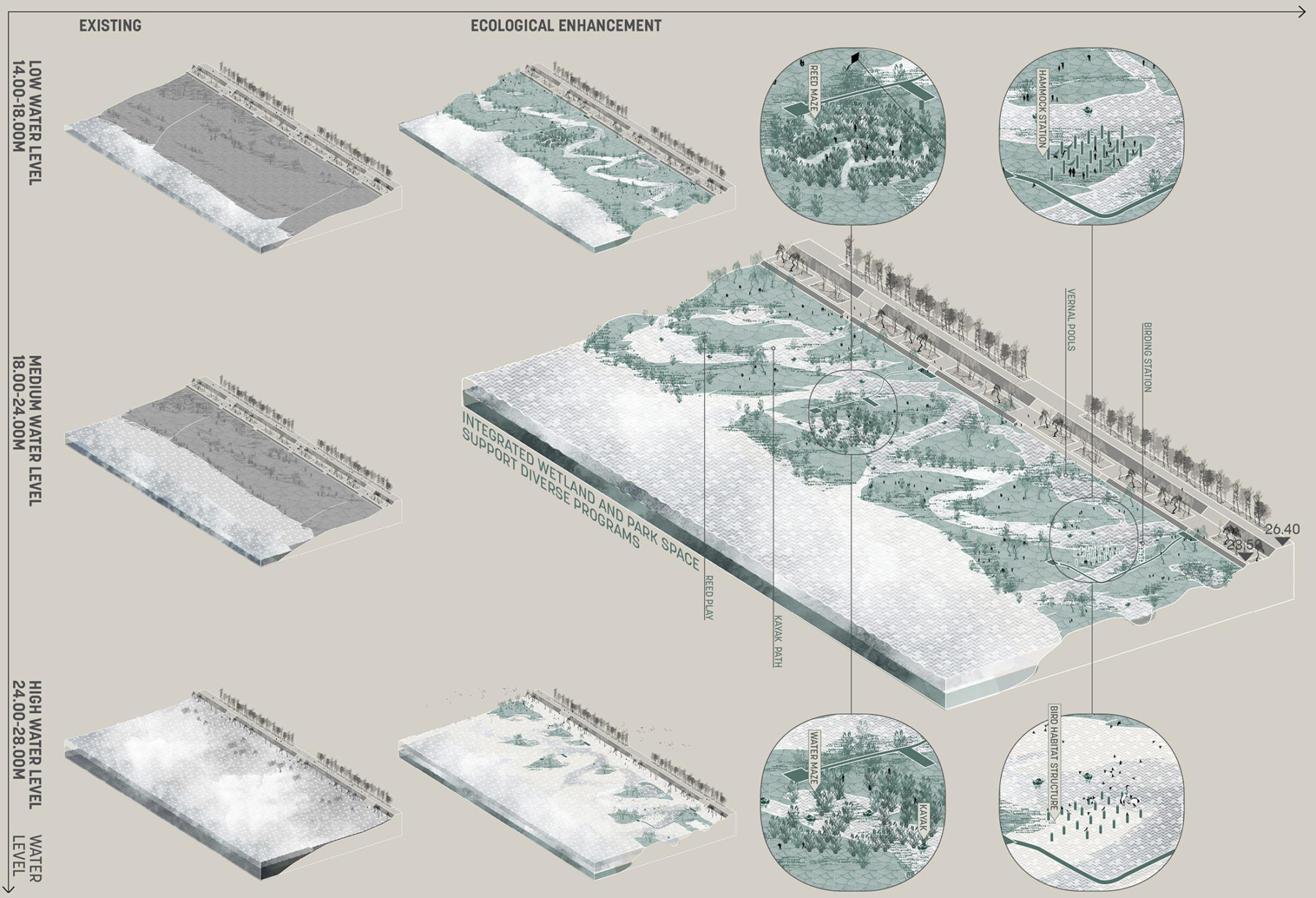

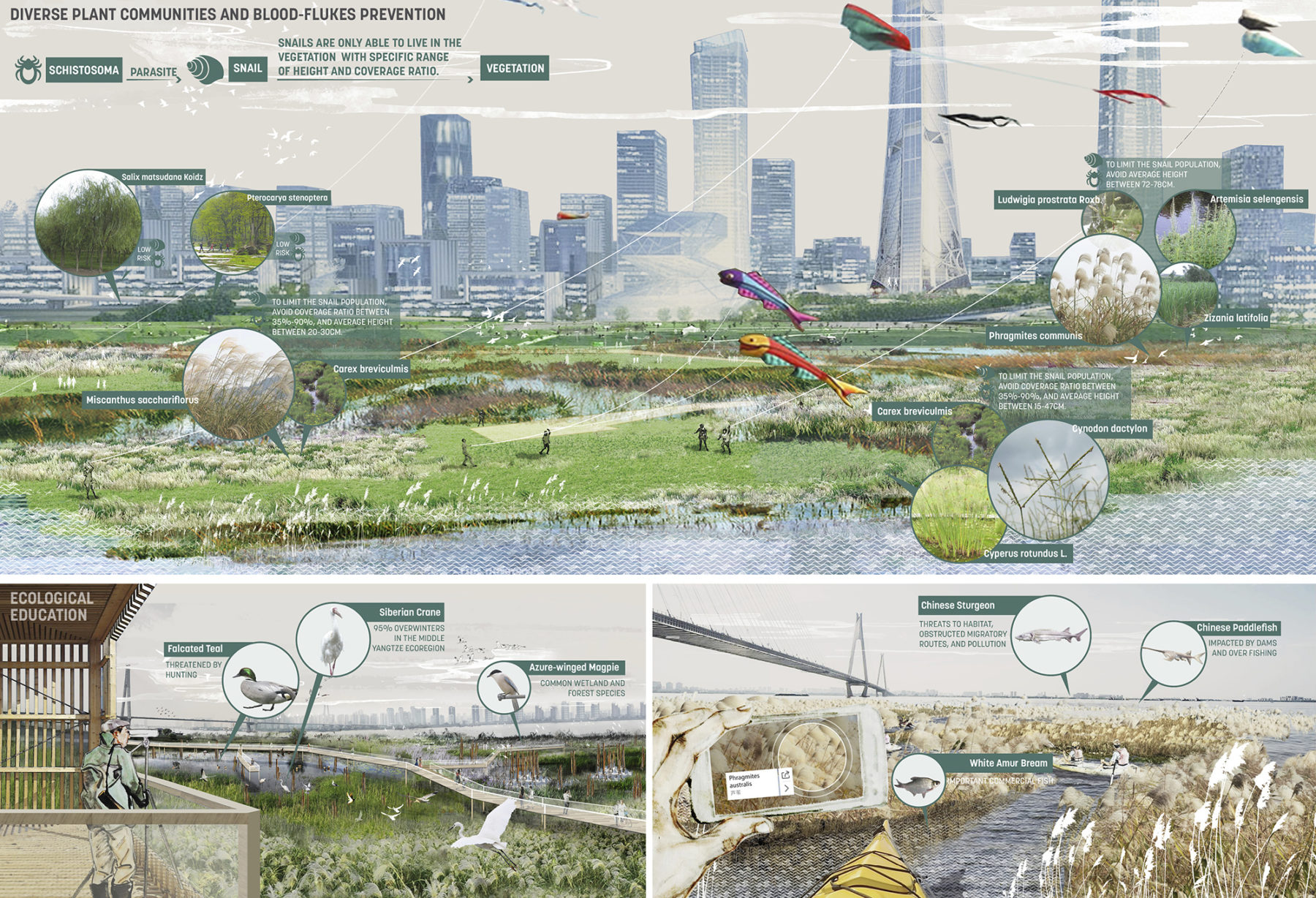

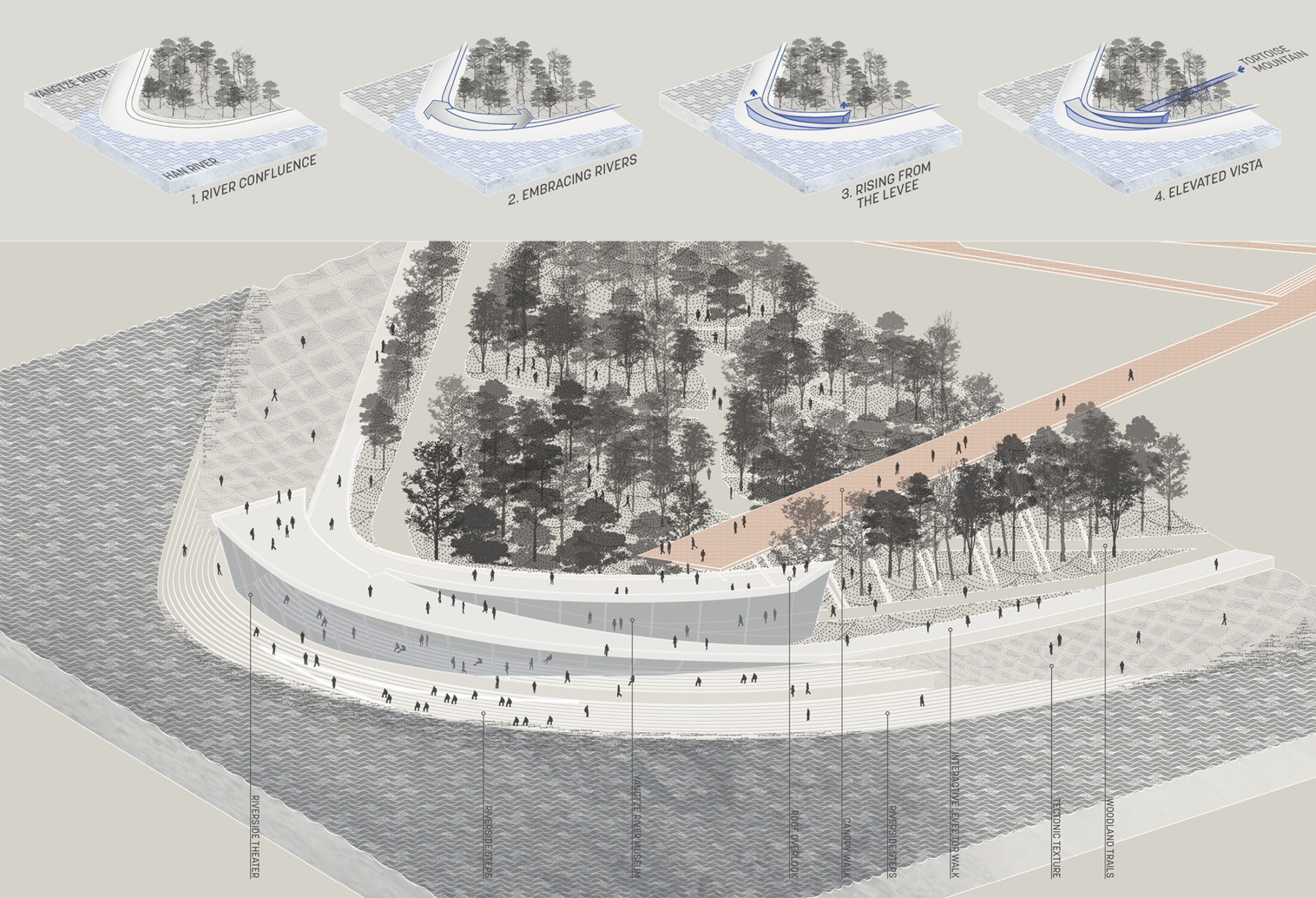

The river’s mudflats continue to play a critical role in supporting biodiversity and delivering crucial ecosystem services, but the sediment flux of the Yangtze River has dropped tremendously due to numerous upstream hydrological projects along the river. The rapid disappearance of these mudflats places regional biodiversity in jeopardy. Through strategic dredging and grading, the design creates heterogeneous microenvironments that host a wide variety of distinct wetland ecosystems in the mudflats. Nuanced topography, coupled with the river’s frequent water level fluctuations, enable complex plant communities to grow. From emergent marshlands to vernal pools, these typologies create an evolving landscape character throughout the year.

Strategic dredging and grading improves the ecological function of the existing mudflats and educate the public about its important seasonal changes

A series of sinuous secondary streams are graded to emerge in the mudflats during mid-high water levels, and provide alternative passages for aquatic wildlife, as well as safe corridors for kayaking. This strategy creates a tranquil experience amid tall marsh grasses, even when the Yangtze’s waters roar. During dry months, these stream beds function as informal pathways for visitors to explore, slicing through the dense grasses.

Nuanced topographic changes, coupled with seasonally fluctuating water levels, unite to establish a dynamic and ecologically complex wetland landscape

Alongside logs for turtles to loaf on and submerged fish structures, waterfowl nesting platforms are installed in the open marsh. Discreet birding stations within the tree groves offer viewing opportunities for wildlife enthusiasts. Recreational spaces are arranged based on careful calculations of the dispersing distances for the key wildlife species in the river basin such that they do not intrude into the primary habitats. During floods, the recreational fields in the mudflats are temporarily returned to the river and repopulated by fish and waterfowl.

Abandoned railyards are adapted as vibrant cultural and recreational uses along the river

When water levels are low, the park reveals its former industrial heritage and offers a unique waterfront experience

Rising water levels triggers an interactive light installation that accents the inundated industrial remnants

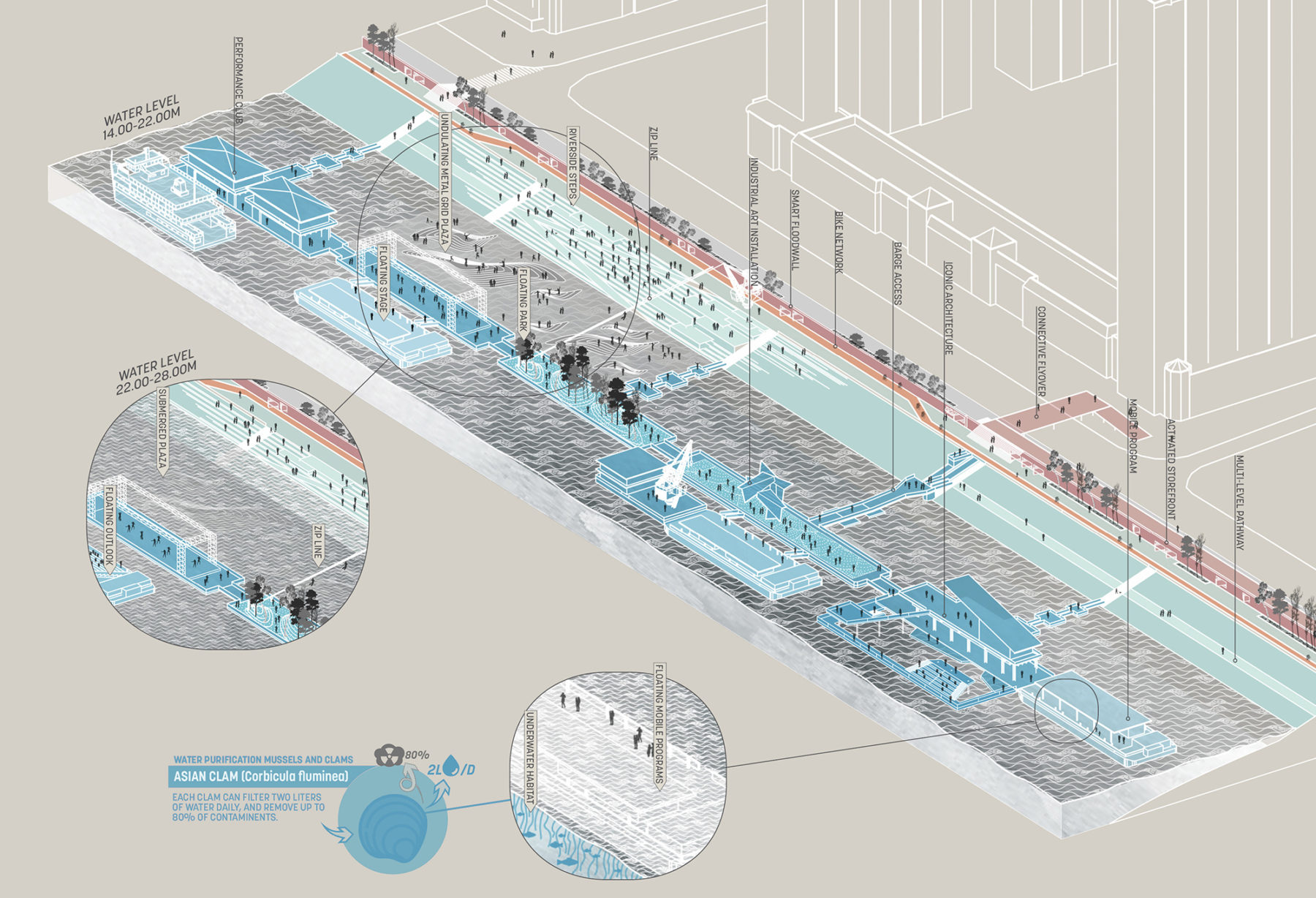

Decommissioned barges are converted to floating parks, performance stages, restaurants, and a floating museum

Abandoned railyards are adapted as vibrant cultural and recreational uses along the river

When water levels are low, the park reveals its former industrial heritage and offers a unique waterfront experience

Rising water levels triggers an interactive light installation that accents the inundated industrial remnants

Decommissioned barges are converted to floating parks, performance stages, restaurants, and a floating museum

Wuhan’s rich industrial history is also celebrated, with historical landmarks highlighted throughout in the riverfront park. Though largely abandoned, the site’s massive railyards and remnants of freight train ferry terminals have a strong visual presence. This heavy-duty infrastructure offers engaging platforms for park visitors to more intimately experience the river, while a series of barges are connected to form a floating promenade. This promenade rises and falls with the river, and delineates a uniquely dynamic space in between. The design of the riverfront park repurposes these industrial relics as vibrant waterfront hubs of new cultural and recreational uses, including floating plazas, restaurants, galleries, and even a floating community garden.

Flexible art and performance spaces promote public understanding and appreciation of river dynamics

The promenade is designed to rise and fall with the river where floodable plazas reveal themselves to accommodate a variety of uses when water levels are low

Submerged during high water events, the plaza accentuates the river’s dynamics and highlights the flexible landscape of the floating garden converted from industrial barges

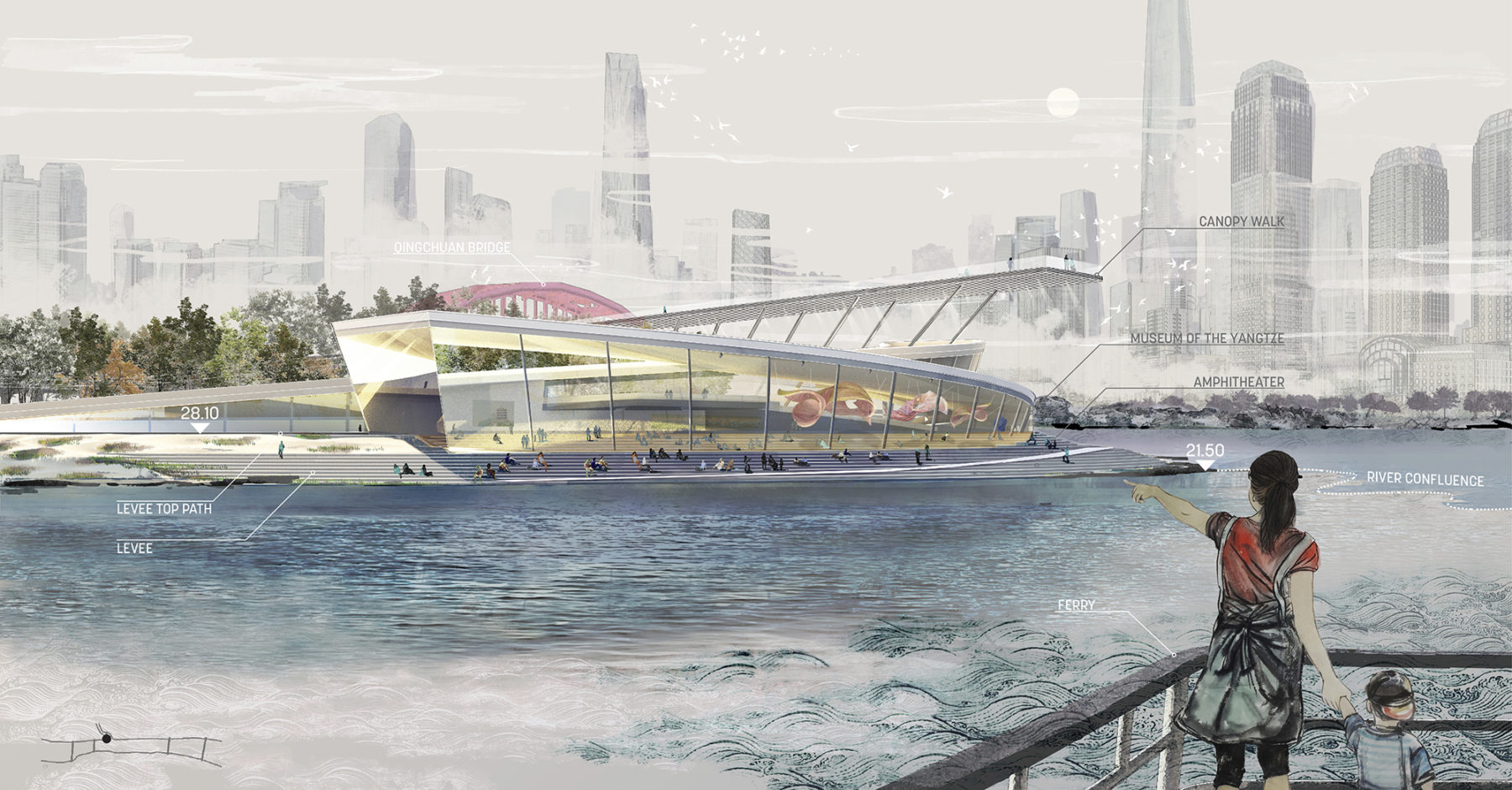

The Yangtze River museum arises from the levee, taking advantage of panoramic views to the Wuhan skyline

At the iconic “Tip of China”—the peninsula at the scenic confluence of the Yangtze the Han rivers—the distinct color of the water of the two rivers clash abruptly with a clearly visible boundary in the middle of the Yangtze. Here, the Museum of the Yangtze rises from the levees and offers an uninterrupted panorama of Wuhan’s waterfront and burgeoning skyline.

The “Tip of China” is an iconic cultural space where the Yangtze and the Han rivers converge

The park provides a landscape foreground to Wuhan’s riverfront skyline

A web-based outreach effort generated fruitful public support of the design, and consensus on the future of Wuhan’s waterfront. Throughout the design process, over 65,000 public comments were collected, helping to inform design various iterations. Local civic groups also organized a series of public meetings and site tours to promote stewardship of the river’s public landscapes. Local youth were also invited to portray their vision for the waterfront park at an event on site.

Preserving the riverfront’s history was vital in the design process

Public meetings and citizen site tours during the design process encouraged community engagement and stewardship of the riverfront

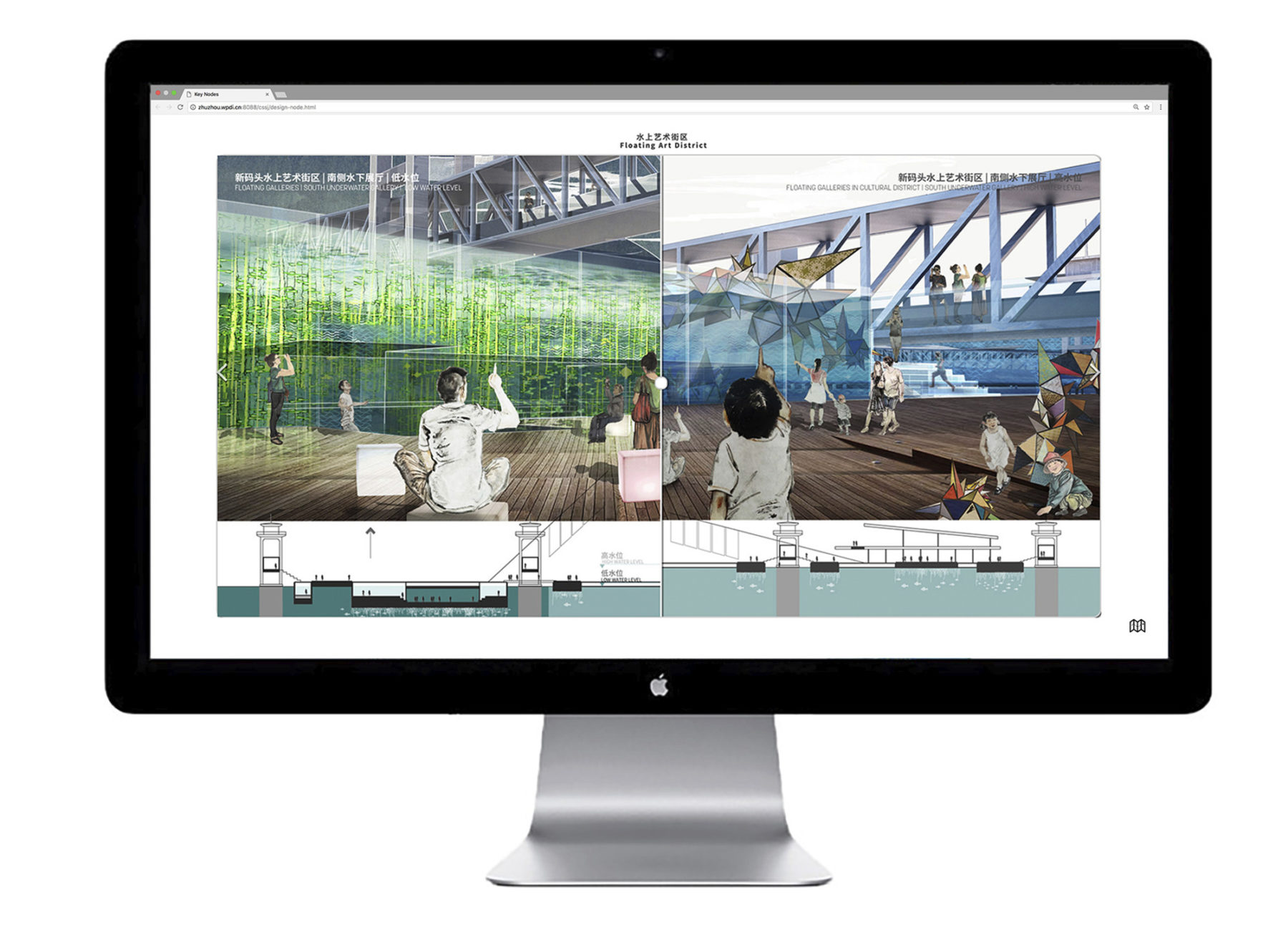

An interactive digital interface was created to encourage and facilitate public engagement which guided an iterative design process

Preserving the riverfront’s history was vital in the design process

Public meetings and citizen site tours during the design process encouraged community engagement and stewardship of the riverfront

An interactive digital interface was created to encourage and facilitate public engagement which guided an iterative design process

Built upon a strong consensus from the public engagement, the master plan for the Wuhan Yangtze Riverfront Park creates a socially inclusive and ecologically meaningful waterfront with a strong cultural identity that embraces the Wuhan’s unique philosophy derived from centuries of living alongside a dynamic river.

Below is a webinar recorded as part of the 2019 ULI Asia Pacific Thought Leadership Webinar Series—delving into our landscape architecture and ecology work for the Wuhan Yangtze Riverfront Park. Narrated by Sasaki principals Michael Grove and Tao Zhang:

For more information contact Michael Grove or Tao Zhang.