The Thunder of Bunnies: Notes on Public Art

Art-makers and city-makers are brushing up against new territories, from ecological resiliency to social activism in the creation of public art

Sasaki

Sasaki

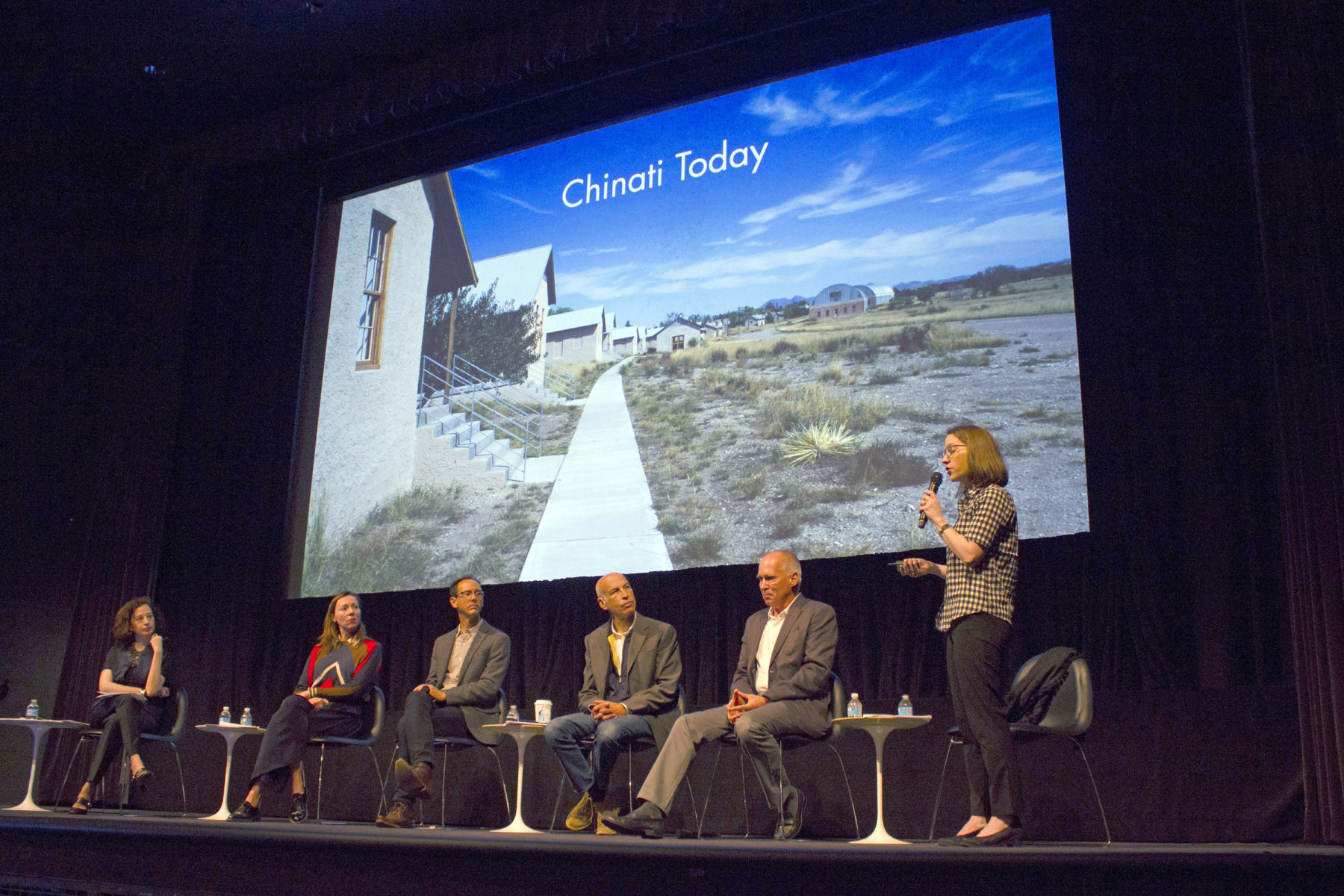

In April, Sasaki principals Brie Hensold and Bryan Irwin, AIA, LEED AP, who led the project team for The Chinati Foundation master plan, presented their work at two symposia. The first symposium was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, followed by the second symposium a week later at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

Over the past year, the Chinati Foundation has undertaken its first master plan since its inception in the 1970s. Located in Marfa, TX, Chinati began when the artist Donald Judd fled the New York art scene and settled in the remote West Texas town. There, he began to implement his concept of a singular place for contemporary art which uniquely integrated experience of art, landscape, and architecture. Today—on the heels of its thirtieth anniversary—the Foundation is at an important and opportune moment in its evolution, leading to the need for a comprehensive master plan for its future.

Chinati is comprised of 34 former army buildings spread across 340 acres of the decommissioned former Fort D.A. Russell, as well as several additional industrial structures in downtown Marfa. The land and buildings have been populated with Judd’s architectural experiments, landscape interventions, and works by Judd and his peer artists. Since Chinati’s inception the permanent collection has grown to include work by Carl Andre, Ingólfur Arnarsson, Roni Horn, Robert Irwin, Ilya Kabakov, Richard Long, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, David Rabinowitch, and John Wesley. Judd’s transformation of Chinati created a place that has drawn visitors from all over the world to make the long journey to this small town, a 3-hour drive from the nearest commercial airport.

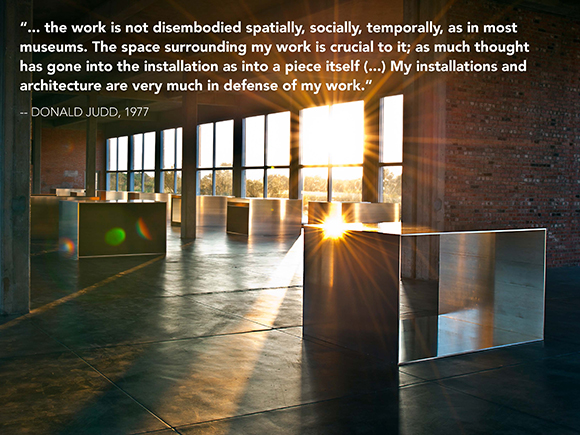

Donald Judd, 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Donald Judd Art © 2017 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The central challenge of the master plan was to uphold and respect Donald Judd’s legacy at Chinati and to maintain the unique experience of the art, architecture, and land. While preservation was a central theme, the Chinati Foundation master plan also contended with a number of changes—new contexts, increasing visitor needs—and sought out ways for the museum leaders to balance adapting and growing while staying faithful to the Judd’s vision.

The symposia at MoMA in New York City and at Chinati in Marfa were the first public unveilings of master plan recommendations. The panelists represented a diverse background including artists, architects, preservationists, historians, critics and curators who were chosen for their ability to offer a unique perspective on the master plan, and Donald Judd’s legacy. At the symposia each panelist reflected on their own personal connections to Chinati, and shared with the audience their immediate reactions to the findings of the Chinati Foundation’s master planning process, which the planning team presented moments before the panel conversations began.

At MoMA panelists included art historian Richard Shiff, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, Ann Tempkin, and Chicago-based artist and urban planner Theaster Gates. The following weekend in Marfa, Chinati gathered Frank E. Sanchis III, Director of United States Programs for the World Monuments Fund, and Billie Tsien and Tod Williams, both principals of the architecture firm Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects | Partners. Both symposia were moderated by architecture writer Karen Stein.

Panelist Theaster Gates responding to the presentation of the master plan at the Museum of Modern Art in New York

Not all master planning efforts are the same. What was special about the master plan for The Chinati Foundation was that it had to remain exceptionally flexible in order to accommodate and facilitate ongoing discussions about the Chinati Foundation’s future. While master planners are often called upon to deliver a bold and transformative vision, in this case the planners needed to remain sensitive and attuned to the particularities of Chinati’s physical setting and philosophy. Through extensive research, conversation, collaboration and design iteration, the team arrived at ideas that enhance, preserve, and amplify the existing mission of the institution.

At the first symposium at MoMA, Chinati’s Director Jenny Moore shared with the audience how she discovered along the way the vitality and usefulness of a master planning process. “This is really a beginning… we now have priorities with buildings, we know what a lot of our challenges are, we know what a lot of our opportunities are, and some questions remain open as we begin to put things in place… The excitement comes out of this process and this really engaging conversation continues.”

Frank Sanchis, a preservationist who was instrumental in nominating The Chinati Foundation to the World Monuments Fund 2014 Watch List, began his remarks at the Marfa symposium by commending Chinati for undertaking a master planning effort, “It doesn’t happen very often at historic sites,” he said, “and it should!” He continued, “In particular, I want to compliment the planning team for coming with such a sensitive and open-minded plan.” Sanchis admired the flexibility of the proposed master plan, describing it as, “Not all nailed-down—doesn’t give you all the big answers, but allows them to be developed—it’s terrific.”

For those who make the journey to Marfa it remains a transformative experience of art and nature. Judd began his career as an art critic, and he wrote extensively about the relationship of art to its environment. His writings form a strong foundation for the master plan. In a 1977 essay Judd set forth the principles that would guide Chinati’s evolution: “The installation of my work and of others is contemporary with its creation. The work is not disembodied spatially, socially, temporally, as in most museums. The space surrounding my work is crucial to it: as much thought has gone into the installation as into a piece itself…. My installations and architecture are very much in defense of my work…. I have to defend what I’ve done; it is urgent and necessary to make my work last in its first condition.”

Since Judd’s death in 1994, the Chinati Foundation has continued to return to Donald Judd’s writings in considering how to continue to manifest his ideas, to make his work “last in its first condition.” During discussion of the master plan at MoMA, moderator Karen Stein asked Sasaki Principal Brie Hensold, what the experience of working at a place with such a singular presence presiding over the work, “almost like a phantom,” felt like. Hensold answered, “I think there are phantoms on every project, definitely. What was very special at Chinati was that we could have a group that has such consistency around mission because of this one singular person and all of his writings, and how powerful his words were. Each of the members of leadership could always go back to that source, and that was a really powerful way to coalesce ideas.”

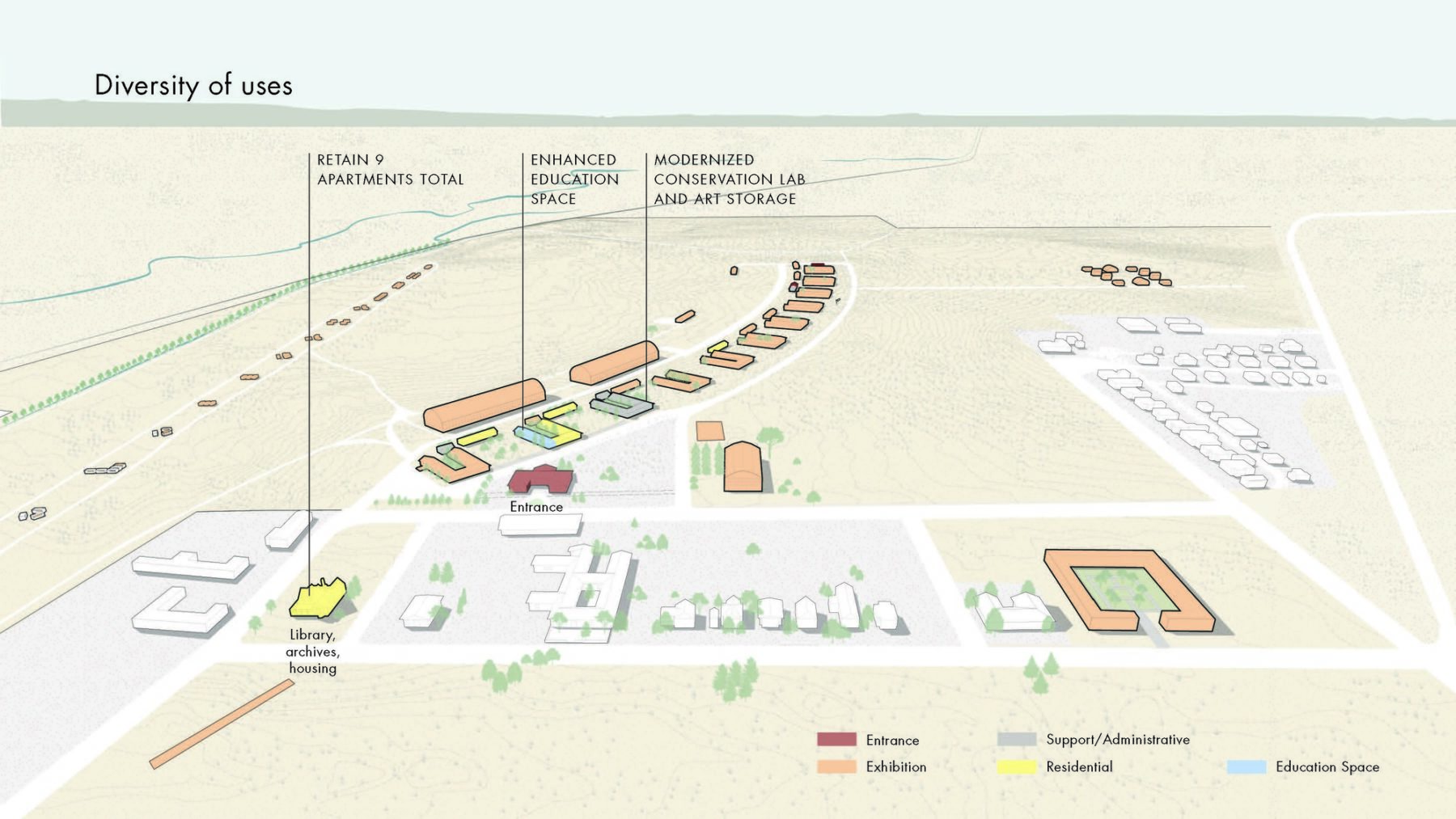

The Sasaki team analyzed various themes central to the experience and future of the Chinati Foundation

The master plan for the Chinati Foundation provides a framework for decision-making for the entire Chinati site, including its art, buildings, land, visitor access, and conservation needs, as well as preservation, and the future growth of the museum. The initial phase of the master planning process concentrated on the discovery of a guiding set of principles—culled from extensive conversation facilitated by the Chinati staff with key stakeholders and community members. As Sasaki Principal Bryan Irwin explained in his presentation, “The staff, the people of Marfa, everyone connected to Chinati are very passionate about the place… We worked with Jenny and her staff to link those together, and identified six guiding principles that became the framework around which the plan was built.” Those guiding principles centered on advancing the mission of Chinati’s creator Donald Judd, the preservation of the landscape and views integral to the experience of the place, maintaining the current casual mixture of programs on the site, and expanding public access to programs and scholarship at Chinati.

Visitor attendance at Chinati has grown quickly in recent years. While in the early days of Chinati, the museum may have experienced a few thousand visitors, last year saw 38,000 visitors arrive to Chinati for tours, programs and other events. If attendance continues to increase at this rate, the plan estimates near 50,000 visitors may arrive by 2020. This growth presents certain demands and challenges when it comes to accommodating larger tour groups, expanding accessibility to all, and creating opportunities for rest along the four-mile route. Today, paths through the former fort grounds of Chinati are informal, encouraging open exploration of the art and land and reinforcing the raw character that is central to the impact of the experience. The master plan develops solutions for accommodating the increasing visitor numbers (and universal access) while simultaneously preserving those essential qualities of the experience. This has included the proposed stabilization of accessible paths, additional places for rest, and a reoriented visitor entrance experience that engages the street.

The master plan advocates for the restoration of Judd landscapes, the creation of accessible paths, and restoration of disturbed prairie lands

Donald Judd’s appreciation for the “undamaged” land at Chinati emphasizes the need for restoration and conservation of the prairie lands. The view of the open ranch lands beyond Chinati’s edges are part of the art itself. Looking east through the fine-edged, heavy concrete frames of Judd’s Untitled Works in Concrete or from the windows of the Artillery Sheds, one can see through a line of cottonwoods that Donald Judd planted along a creek on the eastern edge of the site, over a wide expanse of prairies towards a horizon of low-slung mountains. In recognition of the critical importance of Chinati’s viewsheds, the master plan explored how best to preserve these views and edges. The master plan includes viewshed priorities and a toolkit for preservation including managed relationships with neighbors, local or state regulations, and conservation easements, among others. Sasaki’s teammates from the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, Texas, studied the West Texas prairie, its soils and condition, and how best to restore and preserve the land and plantings in the future.

Many who have experienced Chinati are still passionately connected to it, so the task of proposing any adjustments or changes needs to be approached sensitively and comprehensively. Artist and urban planner Theaster Gates—whose own work in the south side of Chicago integrates art and architecture—said in his comments on the master plan, “There’s no way we can ask Donald Judd what his intent is, or whether or not he feels comfortable about one move or another, but then one has to ask – is there a potential for ideology and philosophical understanding that leads to trust in curation? It requires the making of context… We recognize that there were things that Judd wanted to do that were unrealized and I feel like the important part is the context-making that we do, for ourselves, for our trustees, and for our audience.”

A performance at the Chinati Foundation on Community Day in Marfa. Photo courtesy of The Chinati Foundation © Lachlan Miles

Working within such a context has been an honor for the team of landscape architects, planners and architects from Sasaki, as well as our teammates from Heritage Strategies, Aeon Preservation Services, Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center, Simpson Gumpertz & Heger (SGH), and Lord Cultural Resources, who all worked with Chinati leadership to develop this master plan. In its enduring role as a unique experience of art, architecture and land, Chinati embodies both the transformative potential of place and the power of a clear vision. The work presented by the Sasaki team demonstrates our collective commitment to think beyond the site, to reveal possibility, and advance the mission of our client institutions.

Click here to read more about the master plan on the Chinati Foundation’s website. And check back for more updates soon.