From Paper to Place: How Sketching Shapes Landscape Architecture

Sasaki

Sasaki

Sketching is a tool that can transform design and shape the world around us. A process that brings together form with function, sketching can be a quick, messy exercise or a slow, exacting science. However you sketch, it helps us to imagine, analyze and represent ideas to the world. For me, sketching is essential in unlocking creative potential, fostering collaboration, and transforming complex ideas and landscapes into tangible realities.

Sketching serves as a conduit between thought and form; it also offers landscape architects a unique medium for exploration and clarity. This direct translation of ideas onto paper has been a cornerstone of the profession for centuries. I’ve been reflecting on this recently, especially as it relates to the works of renowned landscape architects like Capability Brown, Frederick Law Olmsted, and our very own founder; Hideo Sasaki.

Designed by Hideo Sasaki, Greenacre Park has been a respite from the hustle and bustle of Midtown Manhattan for decades. Shown here is a drawing of the Park in section.

Sasaki, a pioneer of modern landscape architecture, saw sketching as an essential tool for problem-solving and communication within the practice. His approach challenged traditional methods, emphasizing the importance of human scale and experience in design. For Sasaki, drawings were not merely aesthetic exercises but functional tools that bridged the gap between concept and reality.

Designed by Hideo Sasaki, Greenacre Park includes a series of honey locust trees that allow sunlight into the area and, at the same time, create a protective canopy to screen out adjacent buildings.

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, was a famous 18th century designer who helped shape the English landscape. He used sketches to reimagine and redefine the picturesque English countryside. His drawings served as blueprints for transforming vast estates into seemingly natural, rolling landscapes that have endured for centuries.

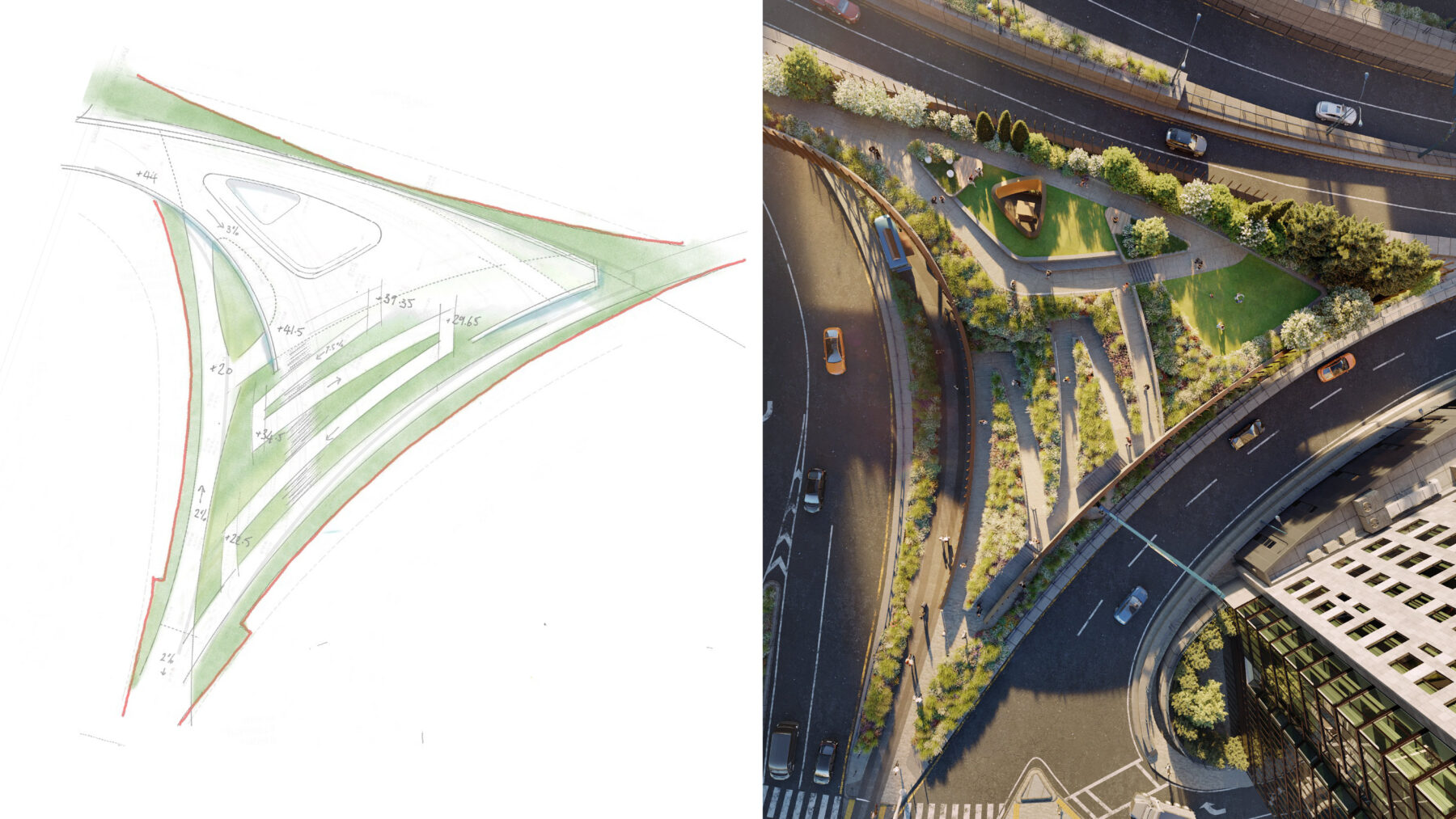

To understand layout and spatial experience, Capability Brown, with his foreman William Ireland, landscaped the park at Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire, which is on a hilltop facing the east side of the Lea Valley. As well as the walled garden, Brown’s scheme included damming the River Lea to create lakes and moving the main road to frame the views. His sketches and drawings reinforce the idea that landscapes are experienced through pathways, changes in elevation, and discovery.

Luton Park, Bedfordshire, Plan for Planting South-East of the House, Lancelot “Capability” Brown British, after 1764

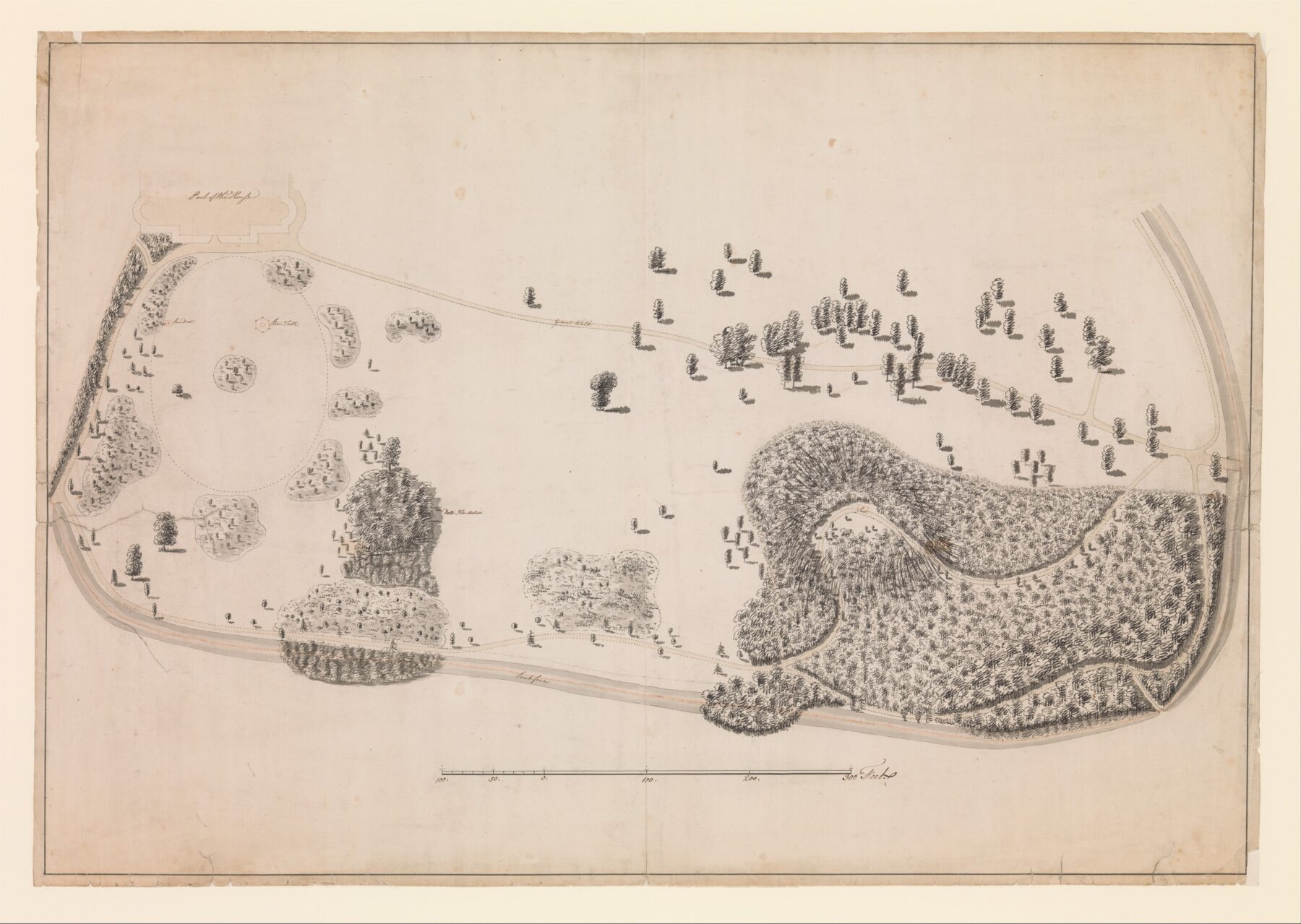

Frederick Law Olmsted, often considered the ‘father of American landscape architecture’ relied heavily on sketching to design intricate urban parks and open spaces. His drawings for projects like Central Park in New York City and the Emerald Necklace in Boston were crucial in visualizing complex spatial frameworks and relationships with natural elements in an urban context.

Franklin Park: Sketch for Ellicottdale Arch. Separating carriage traffic above, from foot traffic below, Olmsted designed the Ellicottdale arch in a rustic-style.

Today, modern technology offers tools for design visualization, but in my opinion, sketching remains unparalleled in its ability to rapidly translate ideas from imagination to paper. The act of sketching engages multiple senses, creating a feedback loop between hand, mind, and environment that fosters a deeper understanding of space and form.

This timeless practice reminds us that the initial spark of an idea, when captured through a sketch, can have a profound impact on the final design. It allows for quick iterations, encourages creative exploration, and often reveals solutions that might not be immediately apparent through digital means.

The beauty of sketching lies in its universality. A simple line drawing can convey ideas with immediacy and clarity. Simplicity gives sketching its freedom; unlike rigid software, sketching allows for intuitive, fluid expression which is crucial when responding to dynamic environments. Regardless of the language we speak or the tools at our disposal, a pencil and paper can convey ideas in real time.

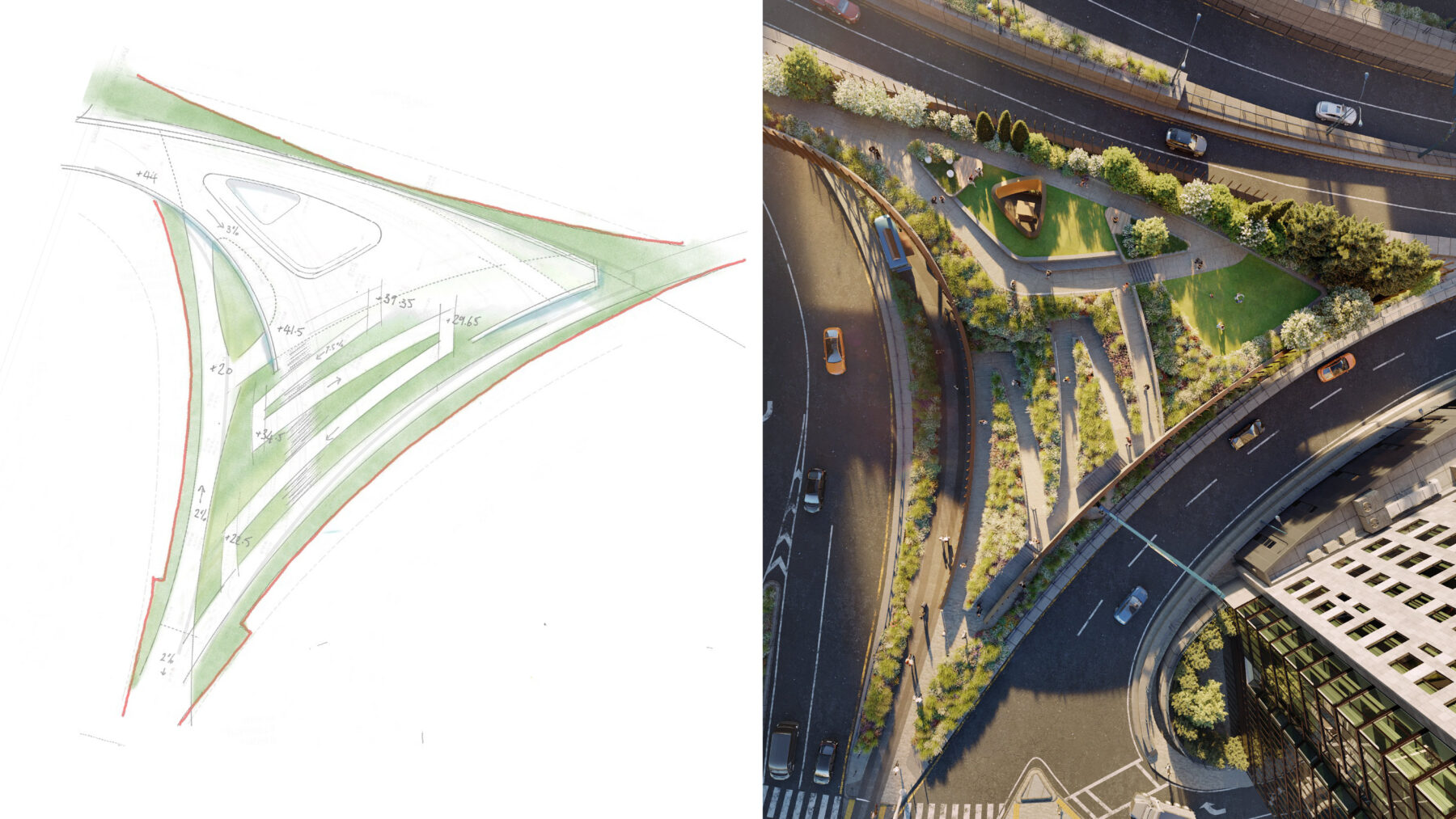

Sketch of site framework for 10 World Trade, navigating the curve of the building edges with the landscape expression

My appreciation for sketching was ingrained during my university years. I was part of one of the last cohorts to begin our education without the digital tools that now dominate the field. Instead, our process was refreshingly analog. We pored over books in the library, scanning pages, carefully selecting images and references. We sketched concepts and ideas over and over again, then meticulously cut and pasted them into sketchbooks.

This hands-on, tactile approach had a profound and lasting effect on my design process. It taught me the value of thoughtful curation, the importance of each line and element in a composition, and the power of visual storytelling. The physical act of searching, sketching, and assembling ideas fostered a deeper connection with the design process and a more intuitive understanding of spatial relationships.

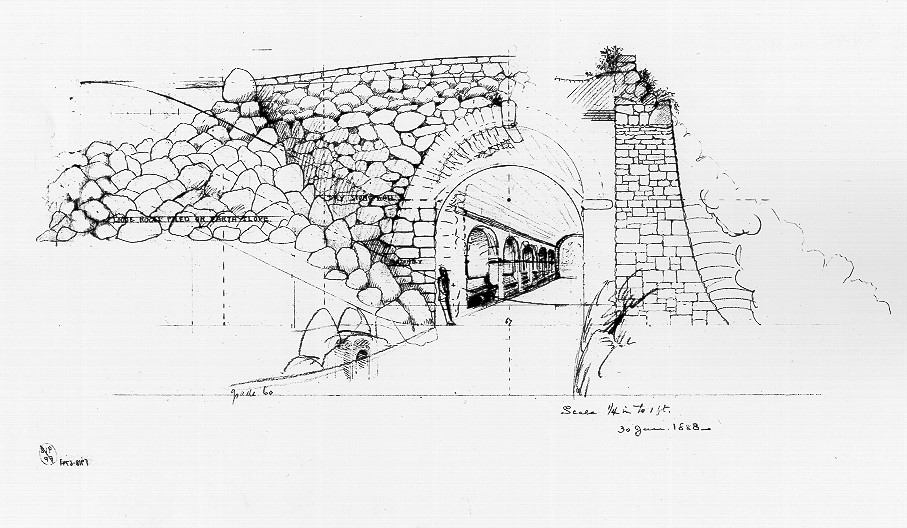

In the early stages of a project, sketches are a way to map systems. They help to understand site conditions, explore ecological networks, and test ideas for integrating resilience strategies. Yet sketching is more than just a tool for systems thinking, it is also about crafting experiences. As designers, we must consider how people will feel as they move through a landscape, the textures they will touch, the sounds they will hear, the sights they will take in.

In Midtown Manhattan West, the site between the river and 11th Avenue is known as Western Rail Yards. In my work, a mix of sketching and photoshop allowed the design to develop into the site masterplan from initial form making through to concept design.

As a systems thinker, I often grapple with the complexity of the public realm. Urban parks, plazas, and waterfronts are not isolated entities; they are interconnected systems that must balance ecology, resilience, and human experience. Sketching is instrumental in navigating these layers with nuance.

Sketching allows us to think experientially. A single line might represent a path, but in my mind, it also evokes the crunch of gravel underfoot or the dappled light filtering through a canopy of trees. These qualities are difficult to capture in technical drawings but come to life through the immediacy of a sketch.

Landscape character ‘chunks’ that define different character zones within a site framework.

From site plans to axons, to eye level views, sketching helps express different scales of experience.

The design process thrives on exploration, and sketching gives the freedom to experiment without fear of failure. A quick doodle might evolve into a bold concept; a scribble can reveal an unexpected solution. Sketching is a way of thinking—it’s how I solve problems, refine ideas, and push boundaries.

Innovation often arises at the intersections of multiple disciplines, and drawing helps navigate these intersections. By layering ideas on paper, you can explore how artistic expressions, ecological principles, and urban systems converge. This approach has been particularly impactful in my own work, where I must balance technical demands with the desire for engaging public spaces. Sketching can start as a simple way to rationally break down the scale of a site, then through exploration and multiple studies evolve into a design expression that becomes synonymous with the project, such as the paving pattern at Wilmington Waterfront Promenade.

In today’s digital age, some may question whether sketching still has a place in the designer’s toolkit. To this, I would argue that sketching is more important than ever. While technology offers incredible precision and efficiency, it cannot replicate the immediacy, spontaneity, and human touch of a sketch. The two are not in competition but rather complementary.

At Sasaki, we leverage cutting-edge tools to analyze data, model landscapes, and create immersive visualizations. Yet sketching remains a vital part of our workflow. It’s how we brainstorm ideas, communicate concepts, and iterate quickly. Even as we embrace digital tools, we must not lose sight of the tactile, analog practices that ground our work in human experience.

For me, sketching is not just a professional tool; it’s a lifelong practice. It’s how I connect with the world, observe its nuances, and sharpen my design instincts. Whether I’m sketching in the field, during a meeting, or in the quiet of the studio, the act of drawing brings clarity and focus.

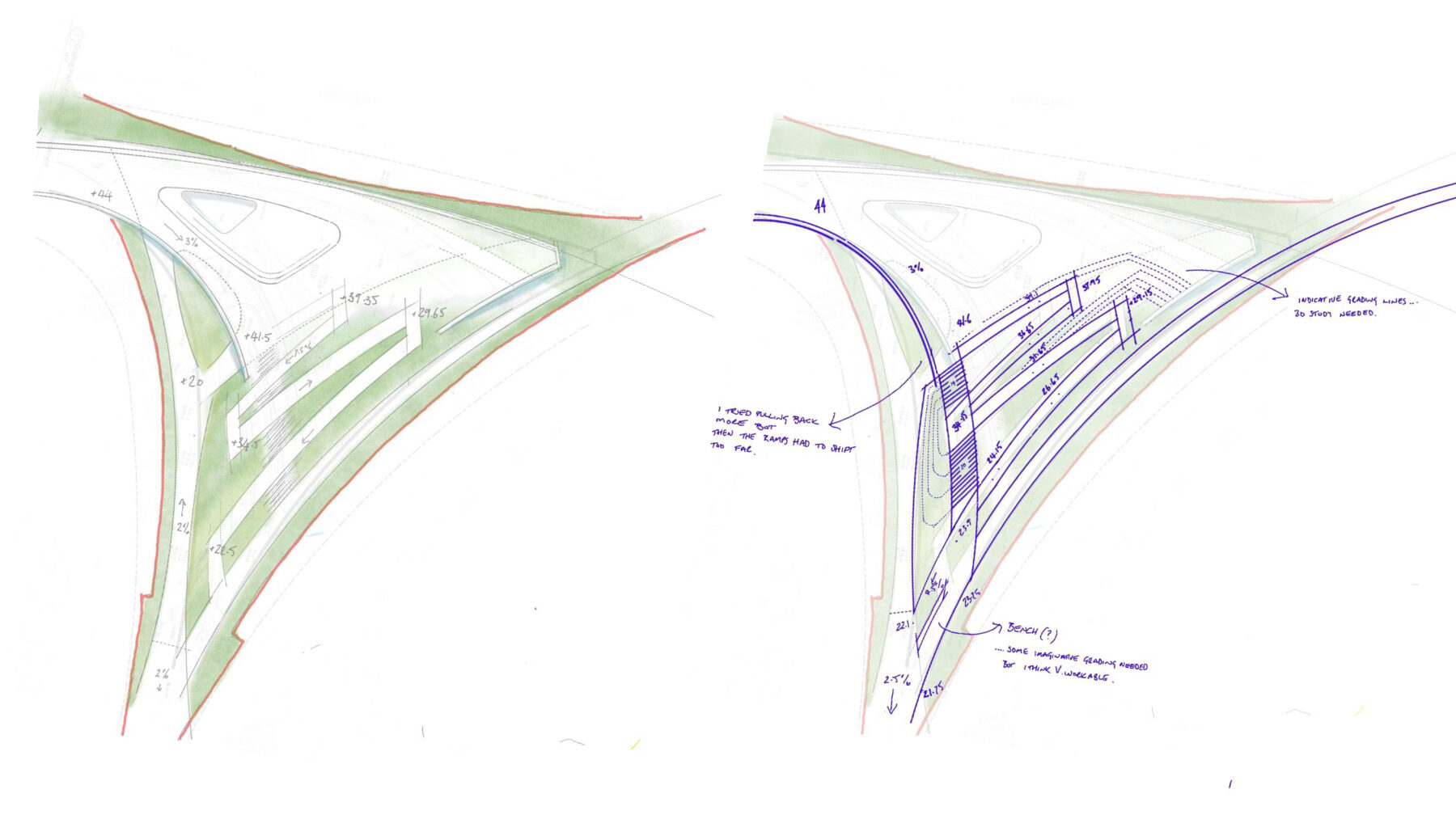

Sketching through form and function, developing circulation and grading strategies at 10 World Trade.

In a profession that is constantly evolving, sketching remains a timeless skill that grounds us in our craft while pushing us towards new ideas. Above all, sketching is a practice of innovation, inclusivity, and connection—qualities that are essential to shaping landscapes that foster a sense of wonder and joy.