Starting a New University? Read This First

Sasaki

Sasaki

In this article, Sasaki Principal Dennis Pieprz, Honorary ASLA, and Senior Associate Romil Sheth discuss the processes involved in developing a new university. Pieprz and Sheth have worked with a diverse range of clients to develop master plans for new universities and campuses around the world, including the Singapore University of Technology & Design (SUTD), West Java New University in Indonesia [pictured above], the Universidad Del Istmo in Guatemala, and the American University of Cairo (AUC).

Q: How does the energy and need for a new university come about?

Romil Sheth: A lot of universities—brand new or centuries old—are shifting from the purely academic fields. Now, many are blending research with real-life applications to provide students with directly employable skills. The mission of West Java University, for example, is very focused on vocation, offering students a skill-based program. That’s one major driver for new schools that we have seen quite a lot, and it’s easy to understand. The spatial needs of this hybrid research/vocational teaching model often require substantially different spaces from what traditional academic buildings are set up for—this creates an advantageous moment for new universities, who can design their program spaces to respond to contemporary pedagogical needs.

Q: Most of the new universities Sasaki has worked with are located in developing countries. Why are we seeing this proliferation?

Dennis Pieprz: Access to higher education in Asia and in South and Central America has been a major trend in recent years. And the resulting proliferation of schools we’ve been seeing has not been limited to state-controlled institutions, either. There has also been a marked increase in the establishment of private universities—especially in China, where the legal requirements for founding new schools are more open to private investment. Many of these countries have experienced booming population growth in the past few decades. As manufacturing has increasingly become centered in developing countries, establishing an educated workforce becomes a priority.

RS: Precisely. Today, people have a much greater awareness of where and how things are made. Companies understand that it makes good business sense to take a product from concept through production in the same country, or at least the same time zone. New universities are serving as talent pipelines for the region’s industry.

Q: What are some other benefits of establishing a new university?

DP: Private sector leaders often see this as an opportunity to transform and advance their society. In some countries, major companies, business, and civic leaders find themselves frustrated by the lack of progress on the part of government. They have the land holdings and resources to set up private universities, and affect change at a faster pace.

RS: There’s a lot to that, bolstering a sense of national pride and confidence. Traditionally, for instance, students from India would go abroad, and their communities would be proud when they brought home degrees from high-ranking Western universities. Today, new universities in their home country are more accessible and stand as proof of the country’s own advancements and academic merits. It also combats brain drain. People who study abroad often tend to stay abroad—while investing in opportunities for young people in their own countries encourages them to stay.

DP: New universities offer established schools many benefits as well. For instance, MIT partnered with the Singapore University of Technology & Design (SUTD) to develop the school’s curriculum from the ground up. Together, they were able to instill a “start-up” mentality into the school that MIT wouldn’t easily be able to do in the United States. MIT is able to see how experimental pedagogical ideas work in practice, while SUTD provides cutting-edge educational experiences for its students. A staff exchange program encourages cross-pollination between the two universities by enabling faculty to spend a number of months at the other school.

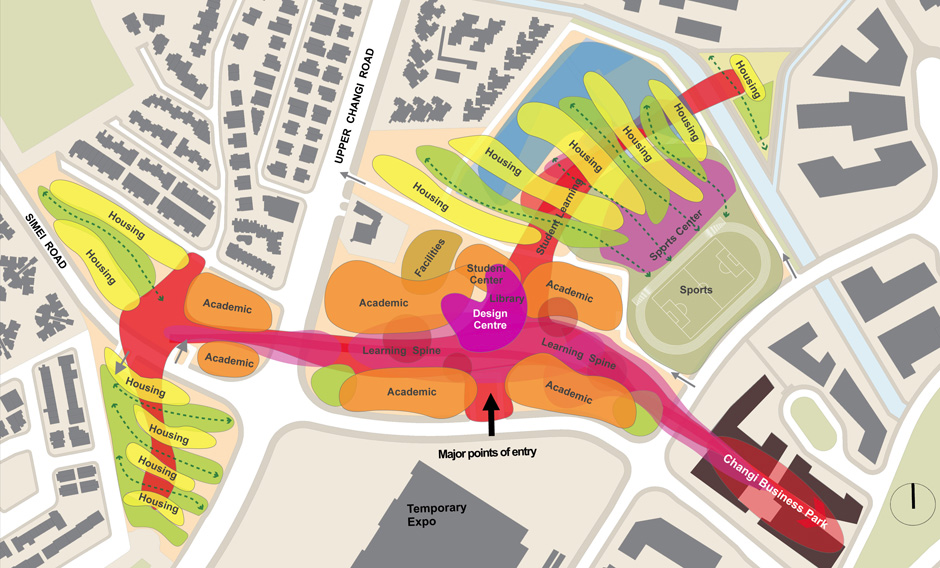

The “four pillars” of SUTD’s academic mission are expressed through a series of flexible classroom buildings

RS: There is an important distinction to consider. Many established schools will build a small branch campus elsewhere—in Beijing or Abu Dhabi, for example—where their students can attend for a semester abroad and students local to the branch campus can apply to study full-time. The difference here is that the fees are higher and the application standards are as stringent as they are at the main campus, meaning that a smaller demographic of potential students is reached. SUTD is an entirely independent university—not a branch campus of MIT—and the school is born from the social and cultural context of Singapore. This enables SUTD to be accessible to a much wider socioeconomic base in Singapore—the specific population for which the school was intended.

Intuitive circulation routes at SUTD encourage idea exchange and informal interactions [Architect: UNStudio. Photo courtesy of Dennis Pieprz]

Q: When does the theoretical impetus for a new university translate into physical considerations? Can you give some insight into site selection?

DP: Each case is unique, of course, but it usually has to do with economics of the country, the players involved, and where the potential school will be located. For instance, our client for West Java University had acquired a previously developed parcel of land near Bandung, a successful university city with over 50 higher education institutions. Though there are many colleges and universities nearby, the client recognized that there was still a growing need for further advanced 21st century education across Indonesia. In response to this need, the client repositioned this parcel to establish a university that offered new pedagogical models.

Q: How does Sasaki translate an academic mission into the spatial design of a campus?

RS: We work with the client to establish a clear idea of their mission. Each university is different. SUTD, for example, was focused on creating highly flexible curricula. They gave us a flow chart with the four pillars of their program: engineering, humanities, architecture, and design. To compliment this flexible pedagogy, we created flexible buildings that can be used by any academic department.

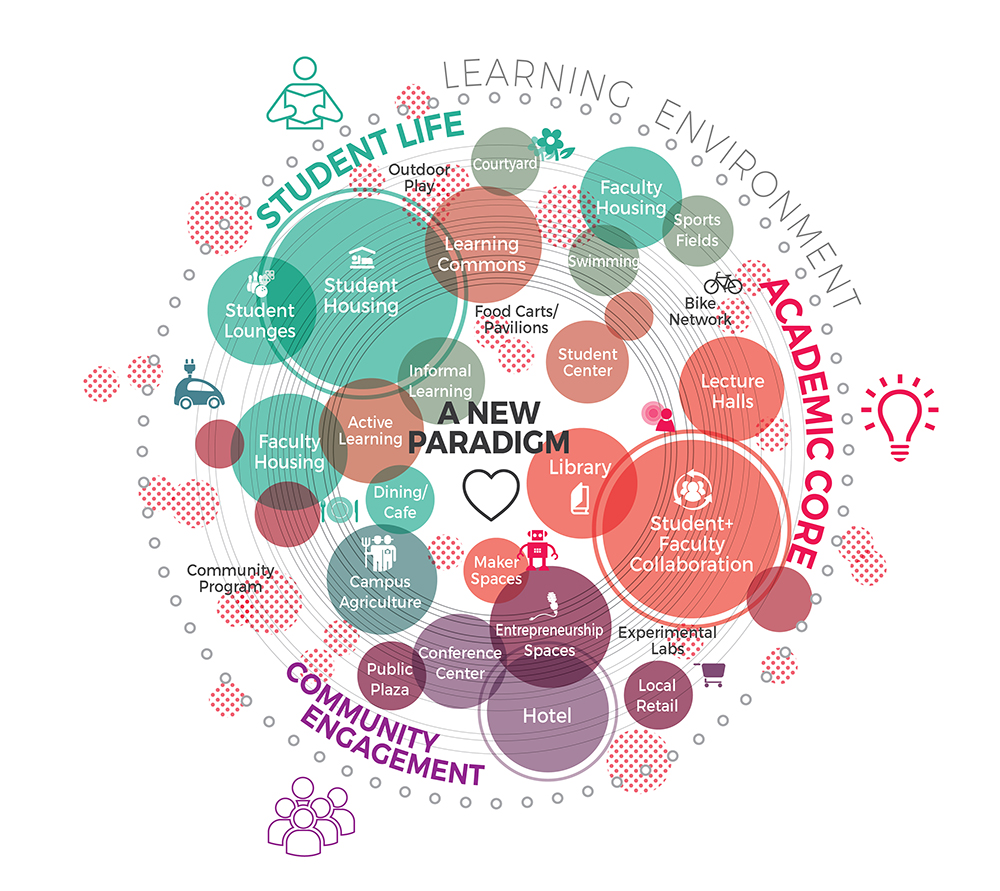

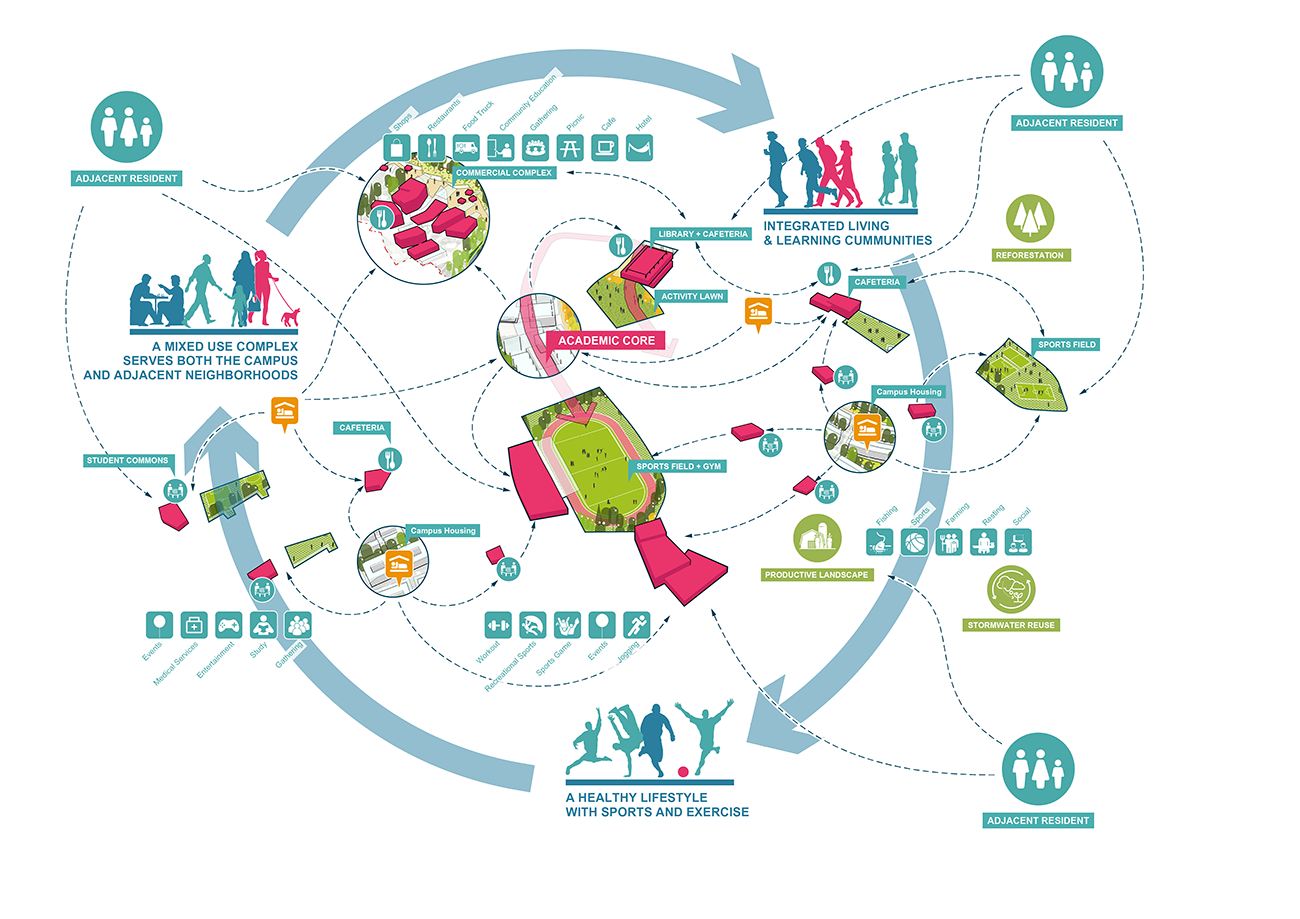

Many schools have a focus on holistic learning, on offering an experience that cultivates the “whole student”—academically, healthfully, and socially. For these schools, it’s important to incorporate the components of student life that encourage health and wellness in a robust way that students can seamlessly integrate into their day. In the West Java University a compact living-learning model is explored that also integrates and enhances existing agriculture practices on site into the campus to create opportunities for food production, learning and research.

West Java University’s mission cultivates the “whole student,” by focusing on academics, student life, and engaging with the community

DP: Each university’s mission informs the initial conceptual and programmatic relationships. Then, in parallel, we look at the culture of the region and the site. Is it an urban or rural site? How does the site trigger a unique response that can merge with ideas about pedagogy, program, and mission? This marriage is very important; a cookie-cutter campus will often fail to inspire students, while an academic experience that fits with the site and the region’s culture will feel instantly more natural. We work very hard to develop plans that bring these two ideas together.

The new campus of the American University of Cairo (AUC) reflects the culture of the region, welcoming students into a familiar environment

West Java University’s campus celebrates the region’s climate, active public spaces, and luscious vegetation

Q: How do you approach phase plans for new universities?

RS: Successful phasing is a key aspect of creating a successful new university. You have to reach a certain critical mass before you can begin generating awareness of what you’re trying to accomplish. It’s hard to attract faculty and students to a school that’s still a construction site, or has no convenient housing options. For SUTD, we planned each phase as a distinct entity. Each phase has academic and student life buildings, and stands as a complete campus.

DP: Our work with the Universidad Del Istmo in Guatemala is a great example of successful phasing. Istmo’s previous campus had become landlocked in an urban district. We developed a master plan for an entirely new site where the school would have space to grow. To get the new campus up and running quickly, portions of the initial core buildings, such as the student center, were used as temporary classrooms. At the same time, the university was able to use their existing campus as new buildings came online and enrollment grew at the new campus. This phasing plan enabled the new campus to design buildings for its expected maximum student population while still providing adequate spaces for its first class.

The Universidad Del Istmo selected a new site where the school would have room for future expansion

Q: What makes for a successful partnership between the university and the planning consultant?

RS: The biggest thing for us, as a planning partner, is to gain an understanding of where the school is coming from. This work is never about imposing an American model, but about making sense of the unique contexts of the project at hand. From that understanding of context, we explore the 21st century learning tools that might work with the school’s mission. A good partner brings a wealth of diverse qualitative experience, as well as benchmarking and spatial data, to help expand and evolve the client’s initial ideas for their school.

Q: What advice do you have for anyone creating a new university?

DP: Find a happy median between planning and design, and the mission and faculty of the new institution. Faculty and students, more than facilities, build energy and excitement at a school. They’re also the people who will have to engage directly with the new academic spaces. If you haven’t made key faculty appointments yet, establish an advisory council as early as you can—this group can prove invaluable in shaping how the school’s mission will be expressed programmatically.

Start a pilot program in temporary facilities to initiate support and interest. SUTD set up in a former nursing school to begin early programs before the main campus was built, allowing them to have programs in place that could shift to the new campus upon completion. A complete education experience suggests introducing on-site residence for students and some faculty. This cultivates opportunities for a more vital and active learning experience. If the foundation of the campus is the academic program, then developing student housing simultaneous to campus construction or finding a partner who can invest in housing makes all the difference.

RS: Higher education, especially in the U.S. and Europe, puts a lot of stock in tradition and prestige. It’s important to not replicate these models verbatim. Harvard and Oxford are successful in their own contexts—when creating a new university, you have to work with your unique context. Take inspiration from established schools, but don’t let that stop you from being visionary. Look at broader considerations, have a good grasp on local economics and global forces, and be open and flexible to new ways of learning, teaching, and collaborating. And don’t chase the prestige that comes from research. New universities shouldn’t expect themselves to be strong research entities on day one. Research comes from accumulated knowledge, and that takes time for schools to build up.