Jinan Streetscapes Advance Planting Approaches

Sasaki

Sasaki

Paris’ Champs-Élysées, Washington D.C.’s Pennsylvania Avenue, Berlin’s Unter Den Linden—these are a few of the world’s most iconic streets. Instantly recognizable to many, these streets have leant elements of their design to innumerable avenues and boulevards around the world. Even without knowing the historical and cultural context of these streets, passersby on well-known streets such as these still feel a palpable sense of place that transcends the logistical aspects of circulation.

To that end, in an attempt to capture the best in street design, we’ve seen civic leaders and designers join in calling for more intentionality in street design around the world; setting a baseline for a greater sense of place and an elevated level of design quality. Initiatives like the United States’ “Complete Streets” program, for instance, and street design guidelines in many Chinese cities are focusing on the importance of safety, sustainability, and liveliness in how we experience streets—while still maintaining the conventional transport functions of accessibility and connectivity.

These initiatives are a step in the right direction, but too often favor the ease of homogeneity over embracing the rich culture inherent in each neighborhood, city, and region. How could they do better? One good place to start would be paying close attention to the stories told by a region’s native vegetation.

Planting, often perceived as merely cosmetic, plays a central role in achieving the goals outlined in street guidelines, such as placemaking, resiliency, pedestrian safety, and more. Prescriptive approaches to streetscape planting underutilize this powerful resource, yet traditional approaches persist. Trees are often planted in predictable straight rows, identical from one street to the next; and designs over-use the few species that are readily available from commercial nurseries, or the few selected from tried-and-true, yet limited, palettes specified in government guidelines. Plantings at the base of the trees, such as bushes, shrubs, or grasses, tend to be divorced from the native habitat of the tree species and are often simply manicured groundcovers or turf grass.

Our landscape practice continually looks for opportunities to challenge and advance this status quo in our world around the world. One such opportunity recently arose, when Sasaki was tasked with developing a streetscape design for a new Central Business District (CBD) in Jinan—the capital of China’s Shandong Province.

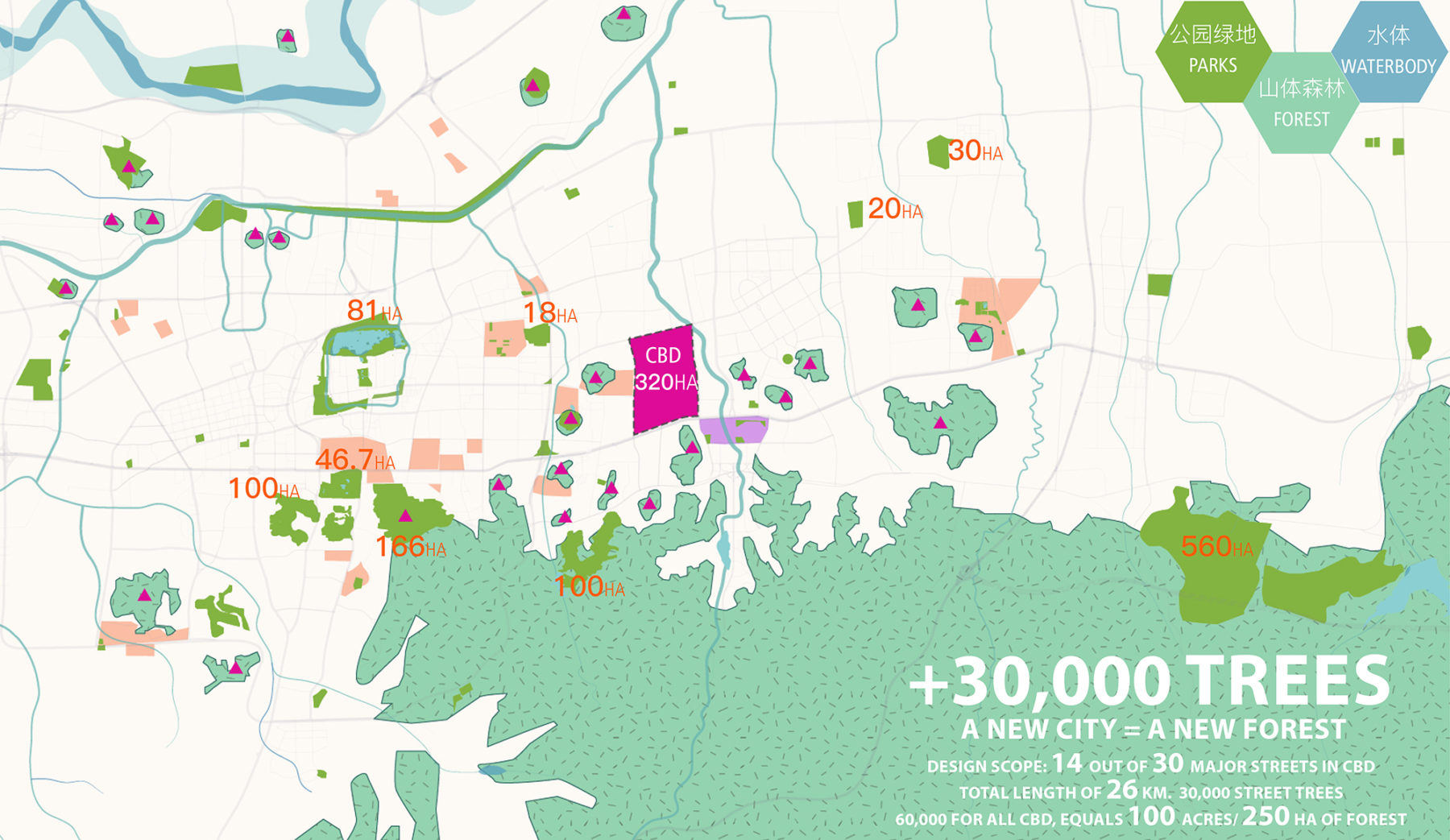

Our planting framework for the Jinan CBD brings the wonder of nature and the unpredictability of the forest to the street’s edge. Departing from the norm, the design creates a completely contextual and ecologically sound streetscape—incorporating 30,000 trees into this more than 320-hectare urban site, and offering an alternative model for future urban streetscape development.

“The scale of this site dwarfs many streetscape opportunities found elsewhere in the world, says Shuai Hao, designer on the project. “The opportunity to drive planting strategy at the district scale is a rare and welcome challenge.”

Trees are integral to Chinese culture, and carry a wealth of symbolic meaning. Trees are indicative of concepts such as longevity, flexibility, and hope; of courage, unwavering friendship, fortune and more. As with many historic cities in China, Jinan proudly links its cultural identity to the symbolism found within its botanical identity. Settled in what was once a great forest, Jinan is still renowned for its many willows—trees which symbolize humility, and instill an atmosphere of harmonious continuity through the city.

The scope of this project included designing streetscape guidelines for 14 of the CBD’s 30 streets, totaling some 26 linear kilometers. The CBD is comprised of seven street types, varying from large-scale major urban connectors and buffer roads to small-scale park canopy walks and recreational ring roads. Each street type has a different range of widths, speed limits, vehicular scales, and adjacent programming.

The seven street types of the CBD are determined by the dimensions of streets, traffic needs, and surrounding land use. We then overlay the planting layer appropriate to each type

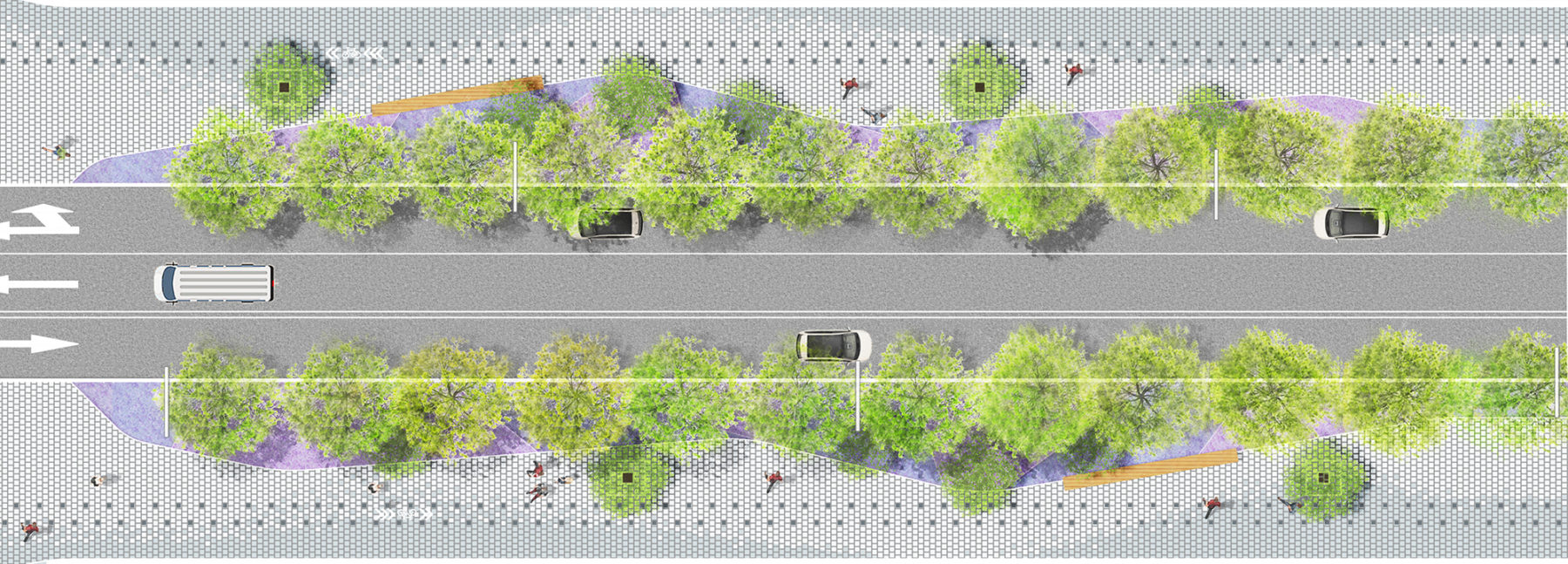

The most significant artery runs along the southern border. Jingshi Road is a 1.7km-long stretch of a ten-lane highway [shown on the bottom of the image above]. The remaining six streetscapes range in scale from 70m wide with eight lanes of travel to a more intimate and narrow 15m width with two lanes of one way travel.

As Jingshi Road passes the CBD, the landscape abutting the highway is designed as a botanical gateway to the new development. Within this gateway, the visitor experiences a full range of native tree species that comprise the remaining six street types. The botanical garden varies in width from 30m to 100m, and the planting species throughout respond to the topographic changes, reflecting the elevation range that each species grows at in its native habitat.

To maintain and celebrate Jinan’s intertwined identities of culture and botany, we devised a series of “forest layers” for the site, which rely on species that carry symbolic meaning and are also native to the region

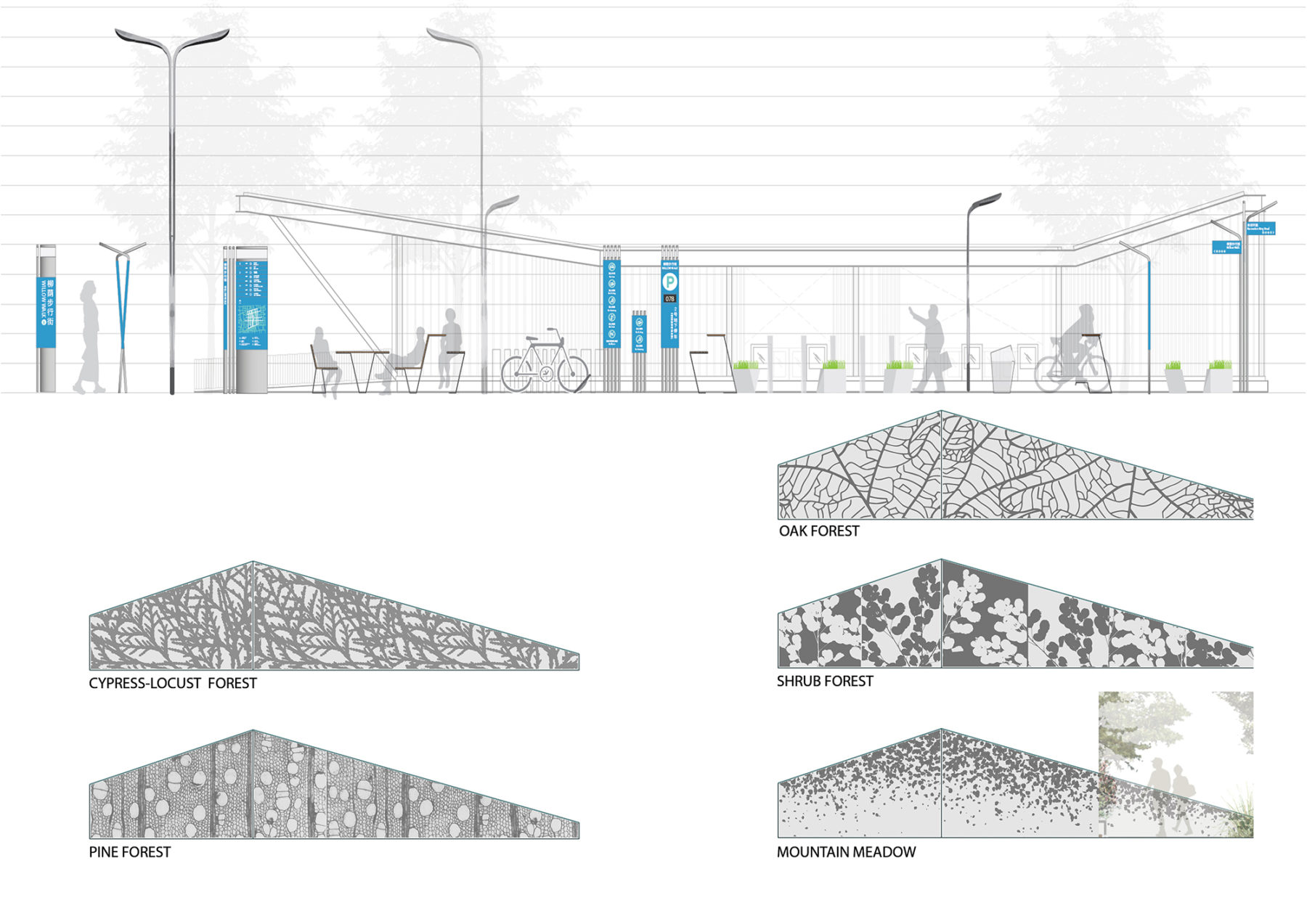

Beyond this gateway, six “forest layers” correspond with the CBD’s street types. These layers are: Oak, Pine-Oak, Willow-Poplar, Shrub, Bamboo and Cypress-Locust. The dominant species within each of these layers helps shape the character of the street type it is paired with. The two buffer roads of the CBD, for example, are defined as more forested “Urban Green Corridors” and use the Pine forest layer; while the “BRT Corridor” adjacent to the high density commercial and retail parcels are lined with Oak, taking advantage of the oaks’ upright bark and high branching point. High grasses are also used instead of shrub planting for understory, to maintain a neat and clean character for these streets.

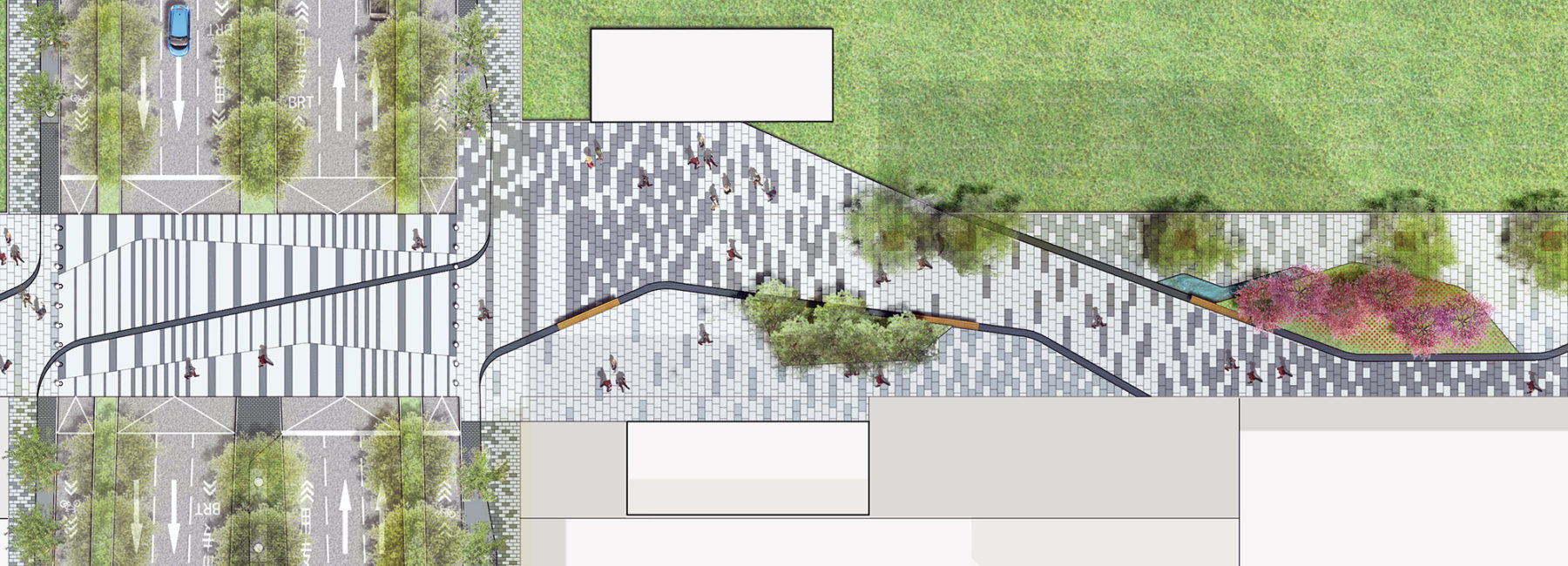

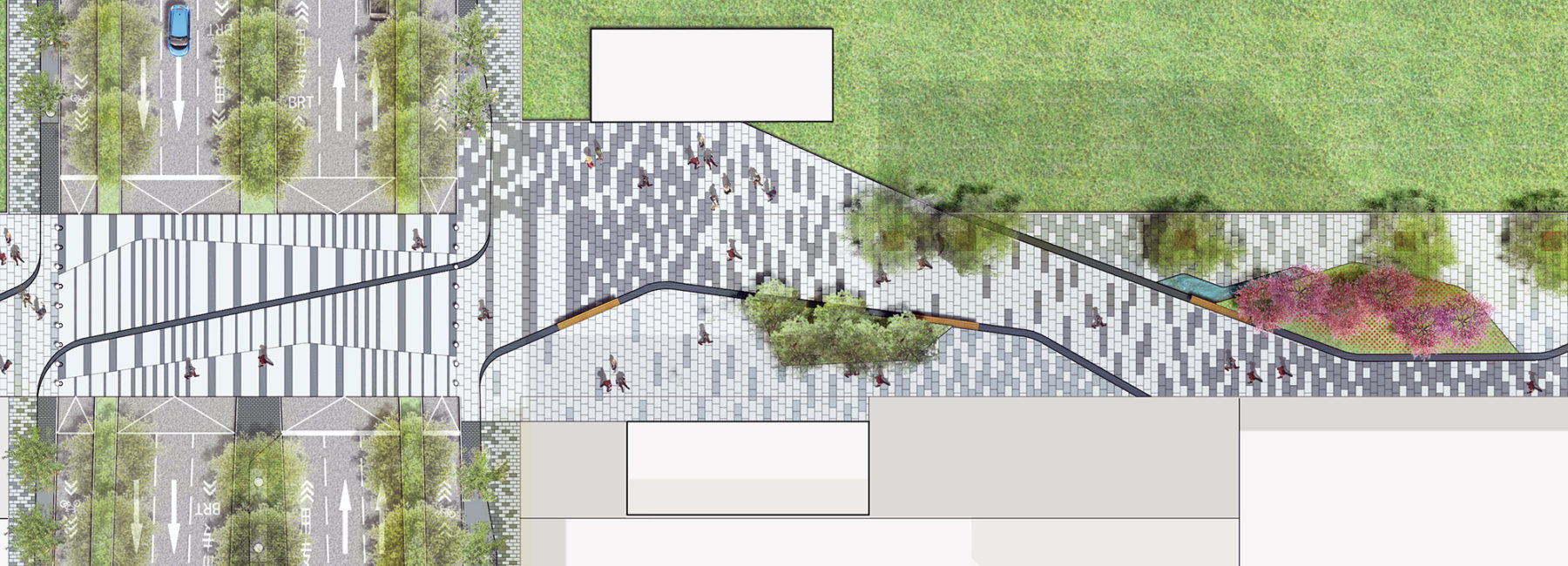

The “Recreational Ring Road,” [pictured below] another street type, consists of four slow-traffic streets for neighborhood residential blocks and four neighborhood parks. This forest layer is designed to have the feel of a garden, with small trees and colorful and textured shrubs from the native Natural Shrub community. The one-way traffic “Park Canopy Walk” adjacent to the site’s ribbon park is tree-lined with white flowering Chinese Fringetree, as well as movable planters filled with species from the meadow and bamboo community. Last, but not least, the east-west pedestrian shopping street [pictured below] is embellished with species from the Willow and Poplar community, tying back to the Jinan’s official city tree.

Recreational Ring Roads: The “garden streets” of the CBD

Pedestrian shopping street

Unique qualities of the trees are highlighted beyond the planting and manifest themselves in the furnishings throughout the site. The form of the lighting, seating, tables and even the structure of pavilions and gates throughout the development highlight unique cell structure, leaves and fruit

All told, the plan calls for 30,000 trees to be planted along 26 linear kilometers of the CBD. It is a massive undertaking that goes way beyond the usual planting schedule found within most government streetscape guidelines. These 30,000 trees will have a transformative effect on the city’s air quality, and stormwater management, as well as providing increased value to the development of the CBD and offering an array of social benefits for the people who live and work in this new development.

Stormwater management strategies are applied to each street type to decrease the city’s flooding risks

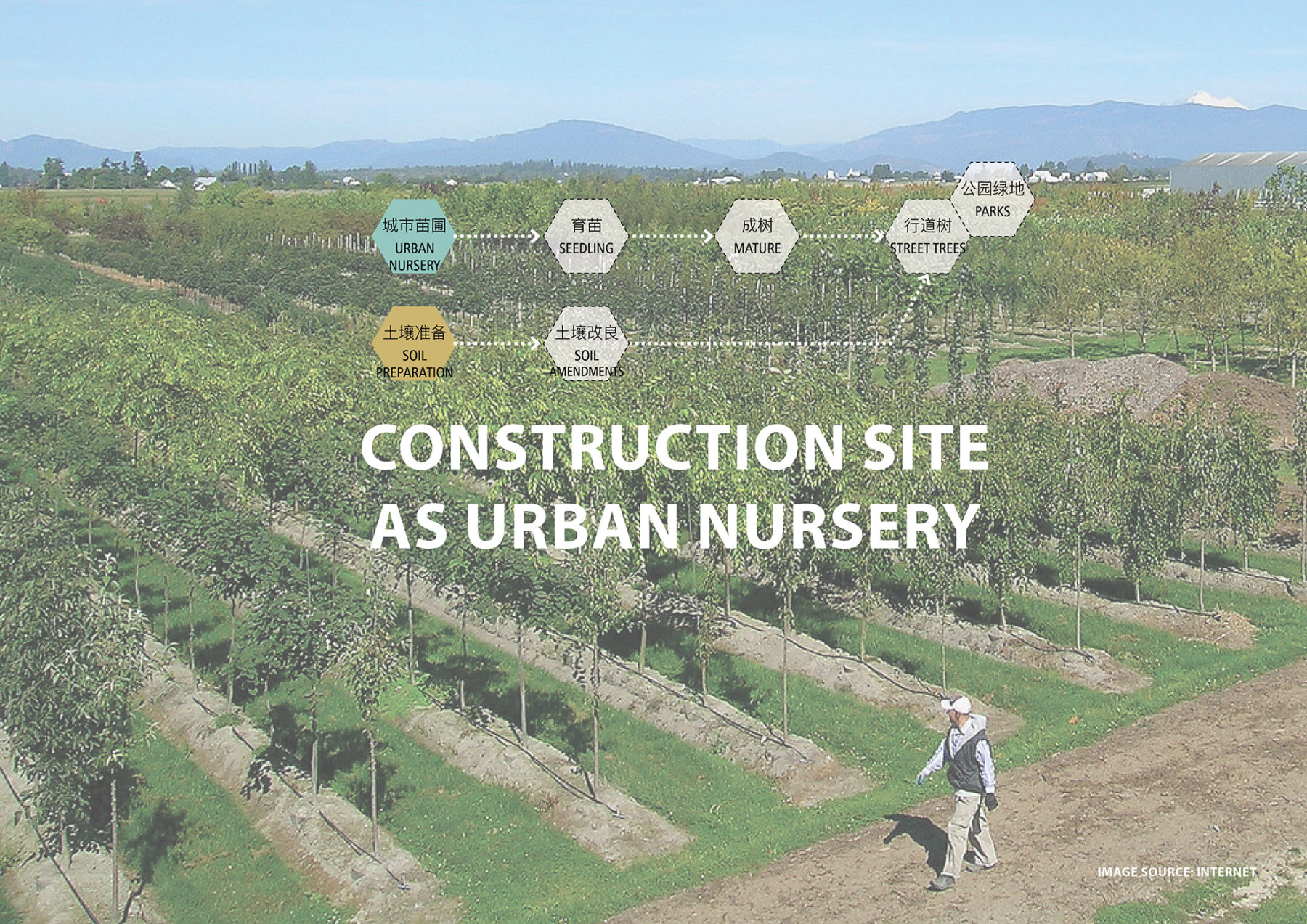

Next comes the unique challenge of acquiring 30,000 trees. This challenge is further compounded by the species we sought: many local commercial nurseries do not grow the native species we specified for this project. Given the scale of the constructible site and the proposed project phasing, we explored the concept of creating an on-site urban nursery.

This innovative approach offers several benefits. Turning a portion of the site into a productive landscape would ensure our access to the desired tree species. Moreover, the health of the trees and their survival rate would be greatly increased by having the vast majority grown locally on site, and transport costs would be significantly reduced.

The phased on-site nursery approach saved the integrity of this project—enabling a true celebration of the intertwined identities of culture and botany, borne of the region’s native species. Many other projects, however, do not have the land availability for such an undertaking, nor the relatively long project schedule needed for growing trees from scratch.

In our practice of landscape architecture around the world, we often face similar problems of species availability when working with commercial nurseries. This limited palette plays a major role in the homogeny of traditionally designed streets. This issue of availability is common, and is largely an issue of demand. Nurseries can only grow plants with marketable value, and too often—regardless of location—non-native species are selected over native species, favored for their aesthetic value more than their ecological viability.

Landscape architects play a critical role in transforming these practices. Changes in supply must be driven by changes in demand. As such, we believe that tirelessly promoting the use of native plant species and sustainable landscape practices is an essential part of our responsibility as landscape architects.