Made in China: Agriculture

Sasaki

Sasaki

Although most of us in the Western world think of the “Made in China” economy as being driven by manufacturing, China is actually the world’s largest producer and consumer of agricultural products. In fact, the agricultural sector represents approximately 13% of China’s total GDP (in the US, agriculture accounts for less than 1% of GDP). Agriculture in China is responsible not only for feeding 20% of the world’s population, but also for employing 22% of Chinese citizens.

But between 1997 and 2008, China has lost over 123,000 square kilometers of farmland to urbanization—a land area equivalent to nearly the entire state of Iowa. Of the arable land that remains, it is estimated by China’s own Ministry of Environmental Protection that one-sixth of this land—roughly 200,000 square kilometers—suffers from soil pollution.

These competing realities sound destined for a frightening collision when considered at their face value. Yet, when placed into a larger context, China’s path may still be righted with a more thoughtful approach to land use, in which agriculture is better integrated into the country’s expanding urban environment.

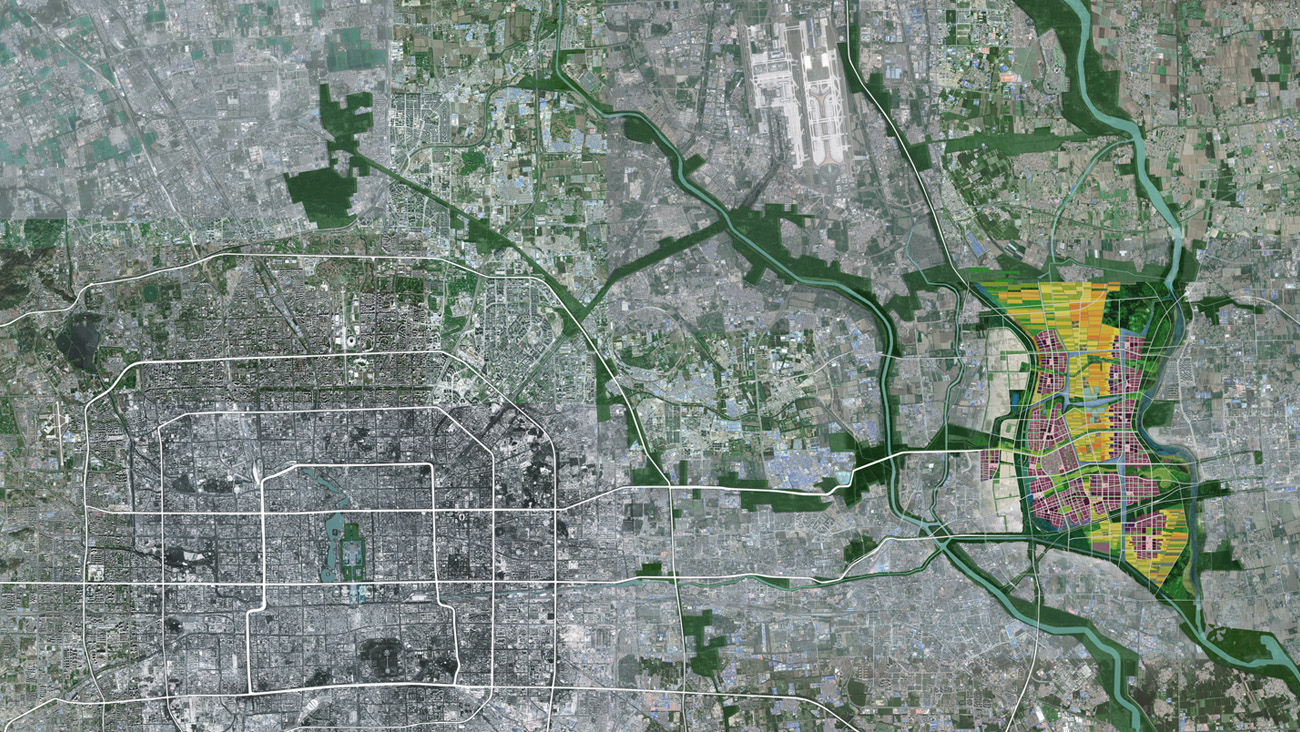

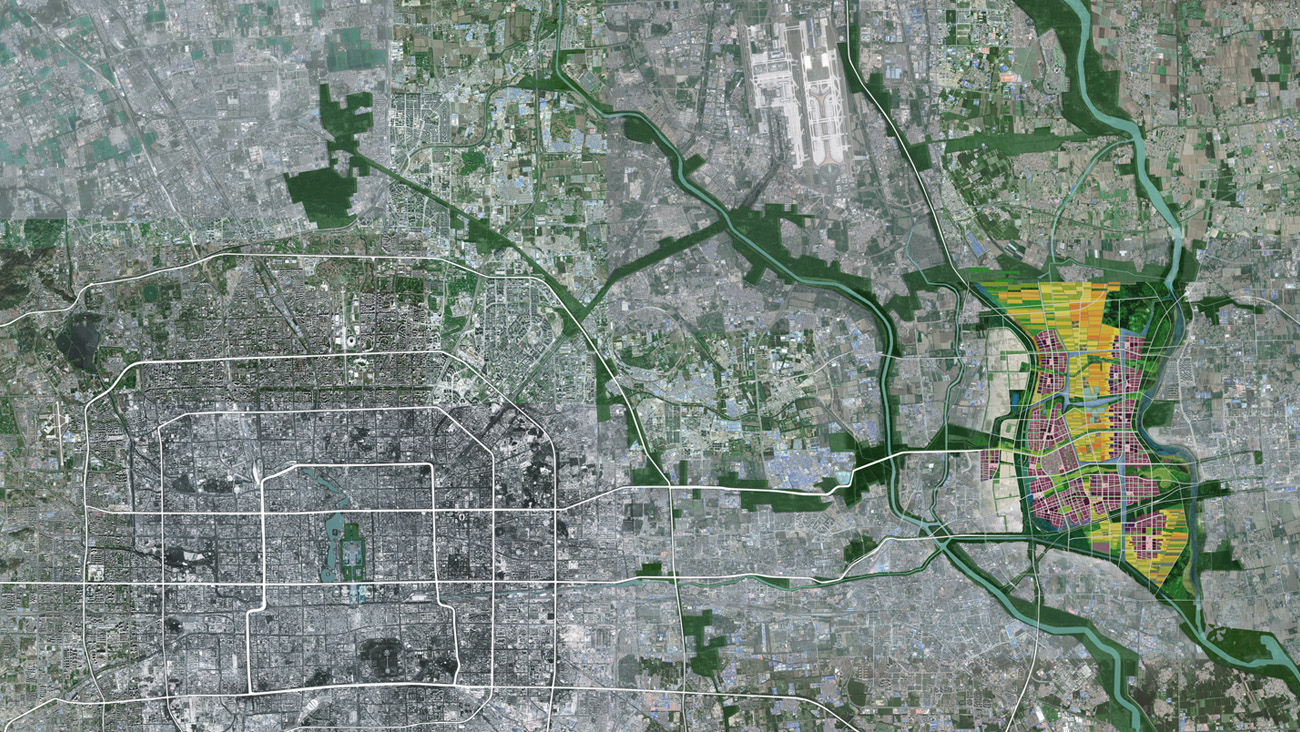

Many growing sectors rely on plant-based materials—think textiles and biotech. With more efficient farming methods and a focus on higher value crops that can be used to support research in these areas, agricultural lands closer to cities can interface directly with business through on-site R&D facilities. Sasaki’s master plan for Songzhuang suggests just that—the development of new economies on the outskirts of Beijing that thrive on their close proximity to the city center as well as to large tracts of agriculture land.

While farmlands are traditionally situated at the periphery of a city, our plan for Songzhuang inverts this approach, locating agriculture at the center of urban development. This creates unique urban conditions that encourage new economic opportunities at the intersection of science and agriculture—and fosters relationships between the Songzhuang community and their food sources. It’s urban farming on a massive scale.

As with any Sasaki master plan, however, Songzhuang takes a systems-based approach, addressing not only the relationship between agriculture and urbanization, but also ecological protection, transportation, engaging the local population, and the physical environment and urban form that will help to create a successful and sustainable community. We’ll be writing a series of blog posts about these macro issues in China, and how Songzhuang functions as a model for how to address them. Stay tuned!

Made in China: Ecology & Landscape Infrastructure by Anthony Fettes