Universal Design in the Age of COVID-19

Sasaki

Sasaki

Thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), over the past 30 years, the United States has focused on accessibility and the need to address the challenges faced by the disabled. Signed into law July 26, 1990, the ADA has transformed many parts of our built environment for the better.

New construction and major renovations since 1990 cumulatively have made this country more accessible—not only for those with disabilities, but also for a range of people: the elderly who are mobile but in need of assistance; families with small children navigating buildings and the public realm; and those who have temporary injuries or other ailments. No doubt, all Americans have benefited from the guidance provided by the ADA.

Thirty years into the ADA project, much has been achieved; however, there is more to be done on college and university campuses if we are to provide inclusive experiences for all learners. What is needed now is a renewed approach to campus planning and design—a method informed by the principles of Universal Design (UD) and deliberate strategies for the delivery of online learning and services.

Today, with the COVID-19 crisis underway, all students are separated physically from the campus environment, bringing emphasis to other dimensions of UD. The crisis has necessitated an online learning experiment that has highlighted opportunities as well as challenges. The opportunities could be a push toward hybrid learning environments that blend physical and virtual engagement in class discussions and group projects. Would this not then be the opportunity to improve on the “experiment” and provide more deliberate and meaningful choices for those who face physical or other challenges in participating in traditional learning environments? As we consider the future of campuses, we should embrace and improve on this experiment to plan campuses that are more inclusive and engaging for all learners.

The challenges of this potential shift to hybrid learning include adapting the curriculum to support in-class, online, and hybrid instruction; creating physical and virtual environments to support hybrid learning; and investing in technology and IT platforms on campus and for remote students who may otherwise lack connectivity. These hurdles, made more difficult by the funding limitations brought about by the COVID-19 crisis, will be key considerations for campus planning and design in the years ahead.

Designing learning environments to accommodate in-class, online, and hybrid instruction must now be a key master planning consideration.

As planners of campus learning environments, we have a responsibility to provide clever solutions for inclusive physical and hybrid learning spaces. This requires a nuanced approach to planning that is informed by UD principles.

UD is defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (North Carolina State University Center for Universal Design 1997).

The origins of UD can be traced to the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University. Originally developed in response to the needs of the aging population and people with disabilities, it is intended to facilitate access to products, places, and services for diverse users. The application of UD principles requires that designers consider a range of abilities, ages, reading levels, learning styles, languages, and cultures to design learning environments that are accessible for all users.

UD focuses on seven principles:

The demographics on campuses have changed, expectations for accessibility have increased, and the current COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need to provide maximum access in flexible ways.

Since the development of UD principles for the physical environment, others have been inspired to create corresponding principles for learning. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) builds on the standards of UD to develop educational courses, materials, and content that reduce the physical, cognitive, intellectual, and organizational barriers to learning. The UDL framework includes strategies for accessible learning in classroom and online settings; by extension, it also provides a framework for hybrid learning environments.

Designing learning environments to accommodate inclass, online, and hybrid instruction must now be a key master planning consideration. Applied broadly to the campus environment, UDL requires a way of providing innovative kinds of spaces on campus, alongside new services, educational delivery models, and communication strategies. Moving forward, master plans will need to embrace the principles of UD and UDL to transform learning environments and support hybrid course delivery.

“Universal Design is not necessarily a specialist subject. In truth, it can be applied by any designer. The first step is to adopt a user- or person-centred approach to designing. This requires an awareness and appreciation of the diverse abilities of people” (National Disability Authority, n.d.). This quote from the Centre for Excellence in Universal Design in Ireland should empower and inspire campus planners to embrace the principles and evolve their approach to planning and design.

As colleges and universities welcome more students with disabilities, a new mindset for the planning process is needed: a UD-driven process. It also must be a conviction guided by students, faculty, and staff with disabilities to ensure that their voices inform the planning process. As an outcome of the COVID-19 crisis, the process also must integrate diverse perspectives from instructors, administrators, students of all walks of life, and IT professionals to develop new hybrid learning infrastructure and methods that are accessible.

A process that integrates physical design and technology is needed, one that includes but is not limited to the following high-level planning considerations.

Campus master plans provide guidance for a number of physical design considerations at the site, building, and room level. Master plans, therefore, must include strategies for a range of conditions, including topographic challenges, access to buildings, and the design of physical and hybrid learning environments. While there are many other considerations, the following examples illustrate the potential for integrating UD into the campus environment. These examples illustrate the need for comprehensive, integrated approaches to planning and design.

Applying UD principles and complying with the ADA on topographically challenging campuses present unique problems for planners. How can significant slopes incorporate routes that are accessible for all members of the campus community? How can a campus-wide network of paths be created with the goal of making the entire campus accessible?

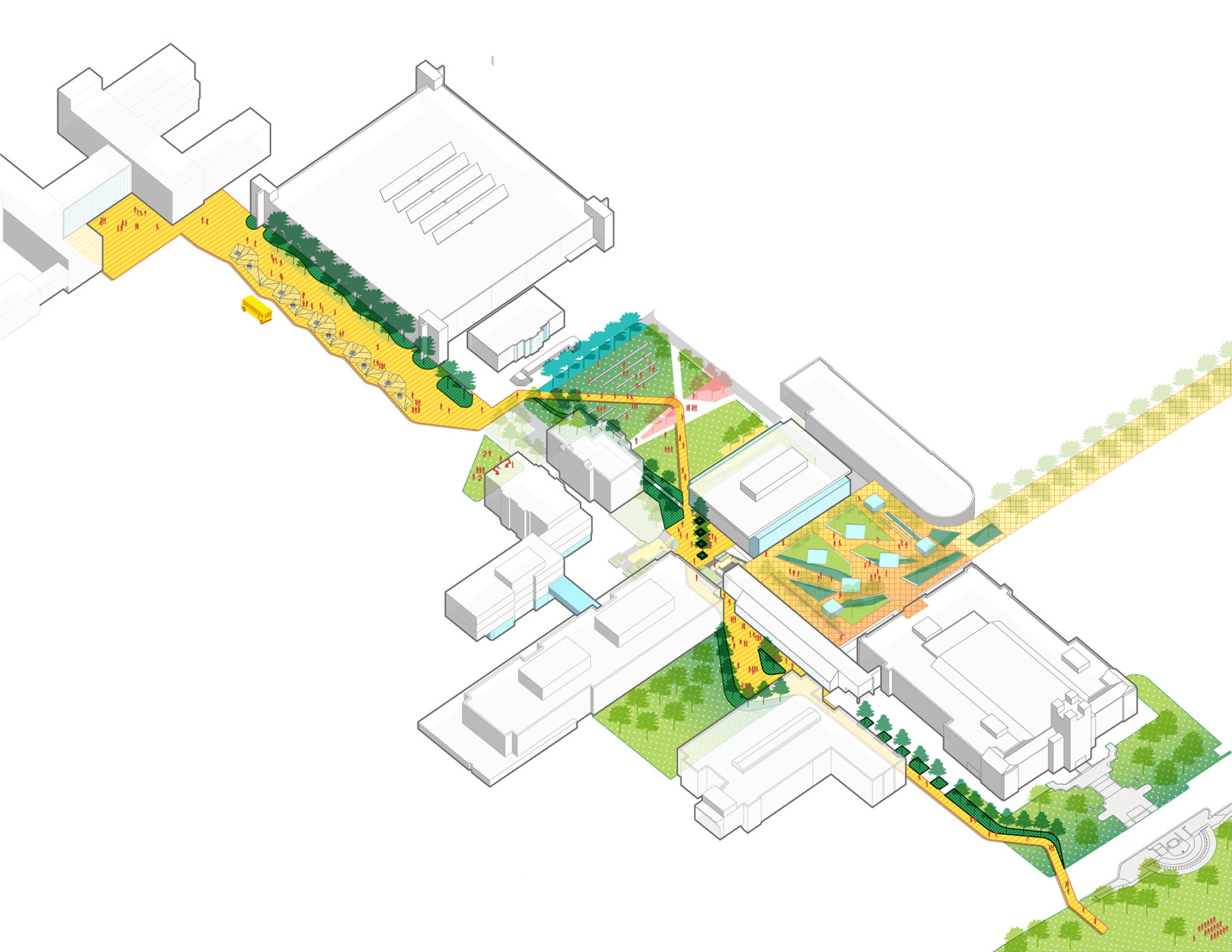

The Virginia Tech master plan addresses these questions through a comprehensive strategy for the challenging topography of the campus. The solution: a network of accessible routes intended for use by the entire campus population, not just those with mobility challenges.

Virginia Tech’s accessible routes: A network of routes with 5 percent slopes or less is planned to address the topographic challenges of the campus.

Each accessible route is designed in response to existing conditions and planned as the primary means of access for all campus users.

Known as green links, these pathways are designed with slopes of 5 percent or less. Collectively, they form a campus-wide system of routes and are envisioned as landscape corridors featuring rest areas, shade trees, high contrast tactile paving, and directional signage. As a network, they are laid out to provide access to major campus destinations including accessible parking areas. The goal is to implement the network over time by coordinating construction with major site and building projects. Beyond this network, site-level accessibility issues associated with stairs, existing entrances, and other impediments to accessibility will be addressed.

Historic buildings can present another challenge for UD. These structures often feature elevated entries with stairs, and they typically lack elevators. At Lincoln University, designated a Historically Black College or University, located in rural Chester County Pennsylvania, a comprehensive strategy provides universal access to buildings in the historic district of the campus. The solution: new “pods” for each building that feature at-grade entries, elevators, and accessible restrooms. The pods are intended to be multifunctional and have egress stairways and mechanical rooms that would be typically challenging to locate within historic structures.

At Lincoln University new entries to historic buildings combined with a comprehensive network of accessible routes are planned to provide a coordinated strategy for campus accessibility.

Existing conditions on the campus of Lincoln University.

Architecturally, the pods are designed as modern additions so as to differentiate them from the original building. At the campus level, this solution is made possible by the fact that changes to the campus layout and population distribution over time have resulted in most users approaching the buildings from the rear. The reversed pattern of movement and the more utilitarian rear facades of the buildings support pods that can be added without changing the architectural character of the original front entrances. It also means that a universal approach to access is possible, given that the most desirable entries to the buildings can be used by all members of the campus population. Beyond the pods, accessible routes with slopes of 5 percent or less are proposed to link the reimagined historic district of the campus to other areas.

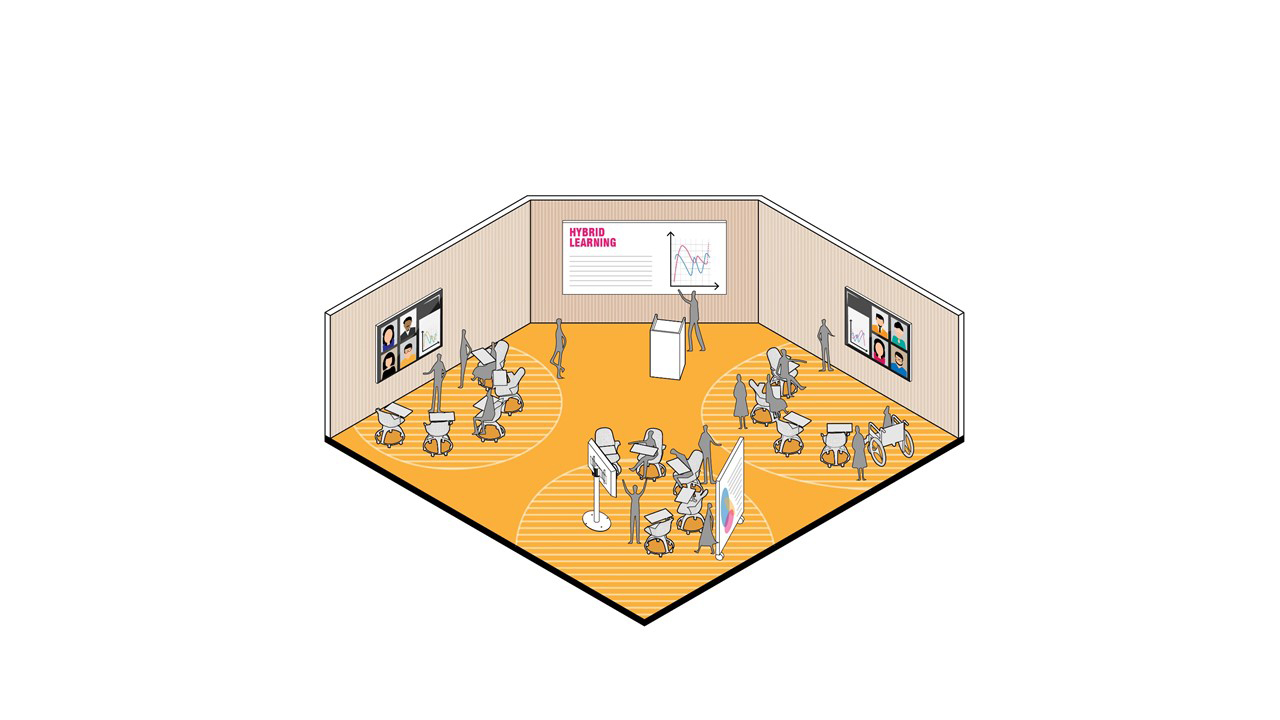

Perhaps one of the more positive outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic could be a new blended world in higher education. It would be a world that includes flexible learning environments that give students the choice of either participating in face-to-face classroom activities or virtually through online engagement techniques, including proxy robots and other emerging technologies. The idea would be to provide choice and flexibility from week-to-week, according to the needs of the student. For those who find travel to campus difficult, the hybrid environment could offer a way to meaningfully participate in the social aspects of learning.

Hybrid learning environments could offer more accessible options by allowing classroom and on-line participants to engage in meaningful collaboration.

The demographics on campuses have changed, expectations for accessibility have increased, and the current COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need to provide maximum access in flexible ways.

From a standpoint of demographics, planners should be mindful that the number of students with disabilities is increasing on campuses, reflecting a more inclusive approach to enrollment. According to a study by the National Center for Education Statistics (National Center for Education Statistics 2018), 11 percent of American undergraduates reported having a disability in the 2007–2008 and 2011–2012 academic years. Undergraduates with prior military service reported disabilities at a higher level than those without: 15 percent in the 2007–2008 academic year and 21 percent in the 2011–2012 academic year. The increases also include students with “hidden disabilities” (e.g., learning disabilities, mental health disabilities, and chronic medical problems).

Thirty years into the ADA, we have made our college and university campuses more accessible but not necessarily inclusive. As we look to the future, now is the time to adopt a new mindset to ensure that our campuses and learning environments become more accessible and inclusive. Imagine how a hybrid model for educational delivery could provide choices for individuals who previously found it challenging to participate in traditional classroom settings due to a host of reasons (e.g., physical limitations to mobility; economic realities that necessitate flexible work and school schedules; child care responsibilities that may create interruptions throughout the day and night; and financial limitations that preclude the expense of travel, moving, and room and board that is traditionally expected for students to participate fully in undergraduate programs).

An intensified focus on the principles of UD and UDL will be a game changer for those who have championed a more thoughtful, inclusive design of physical places and pedagogical delivery as well as those who face personal, economic, and transportation challenges. Applied broadly, UD requires planning and design responses that go beyond site and building considerations to include new types of learning, research, social, and other environments. It also requires new services, educational delivery methods, and communication strategies. Now is the time to imagine the campus environments we would like to see and adjust our mindset to deliver master plans that will guide us toward more inclusive experiences and choices for all, whether they be delivered on campus, online, or in hybrid environments.

Connell, Bettye Rose, Mike Jones, Ron Mace, Jim Mueller, Abir Mullick, Elaine Ostroff, Jon Sanford, Ed Steinfeld, Molly

Story, and Gregg Vanderheiden. The Center for Universal

Design, “The Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0.,” 1997, https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_ud/ udprinciples.htm.

National Disability Authority. n.d. “10 Things to Know about UD.” Accessed May 26, 2020, http://universaldesign.ie/ What-is-Universal-Design/The-10-things-to-know-aboutUD/.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, “Digest of Education Statistics: 2017, Chapter 3: Postsecondary Education,” 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/ programs/digest/d17/ch_3.asp.