Suburban Sprawl Increases the Risk of Future Pandemics

Sasaki

Sasaki

This article was originally publshed in ASLA’s The Dirt.

The export of American culture is one of the most influential forces in our interconnected world. From Dakar to Delhi, American pop music, movies, and artery-clogging cuisine is ubiquitous. However, one of the most damaging exports is the American suburb. When the 20th century model for housing the swelling populations of Long Island and Los Angeles translates to 21st century Kinshasa and Kuala Lumpur, the American way of life may very well be our downfall.

In our pre-pandemic ignorance, most urbanists pointed to climate change as the most dangerous impact of our cherished suburban lifestyle. To be sure, the higher greenhouse gas emissions and rise in chronic health problems associated with living in subdivisions aren’t going away, but COVID-19 has exposed another threat we’ve chosen to ignore. The next pandemic may very well result from our addiction to—and exportation of—sprawl.

The increasing traction of the anti-density movement in the wake of the current outbreak is alarming. Headlines proclaiming how sprawl may save us and that living in cities puts citizens at higher risk for contracting the novel coronavirus are deceptive.

Recent studies have debunked these myths, finding little correlation between population density in cities and rates of COVID-19, instead attributing the spread of the virus to overcrowding due to inequity and delays in governmental responsiveness.

Mounting evidence suggests that COVID-19 is primarily transmitted through close contact in enclosed spaces. Internal population density within buildings and, more specifically, within shared rooms inside buildings is what drives this, not the compact urban form of the city. In New York, for example, COVID-19 cases are concentrated in the outer boroughs, and suburban Westchester and Rockland counties have reported nearly triple the rate per capita than those of Manhattan.

The real issue is the systemic economic inequity that forces lower income people to live in overcrowded conditions, regardless of location. Innovative approaches to urban planning, equitable housing policies, and a reversal of over a century of environmental discrimination in our cities are absolutely necessary. Vilifying the city is counterproductive.

Moving out of dense cities into the open space and social distancing afforded by the suburbs is exactly the type of knee-jerk reaction that we must avoid. Cities are not at fault.

In fact, cities are the answer if we plan them carefully. Among the many human activities that cause habitat loss, urban development produces some of the greatest local extinction rates and has a more permanent impact. For example, habitat lost due to farming and logging can be restored, whereas urbanized areas not only persist but continue to expand.

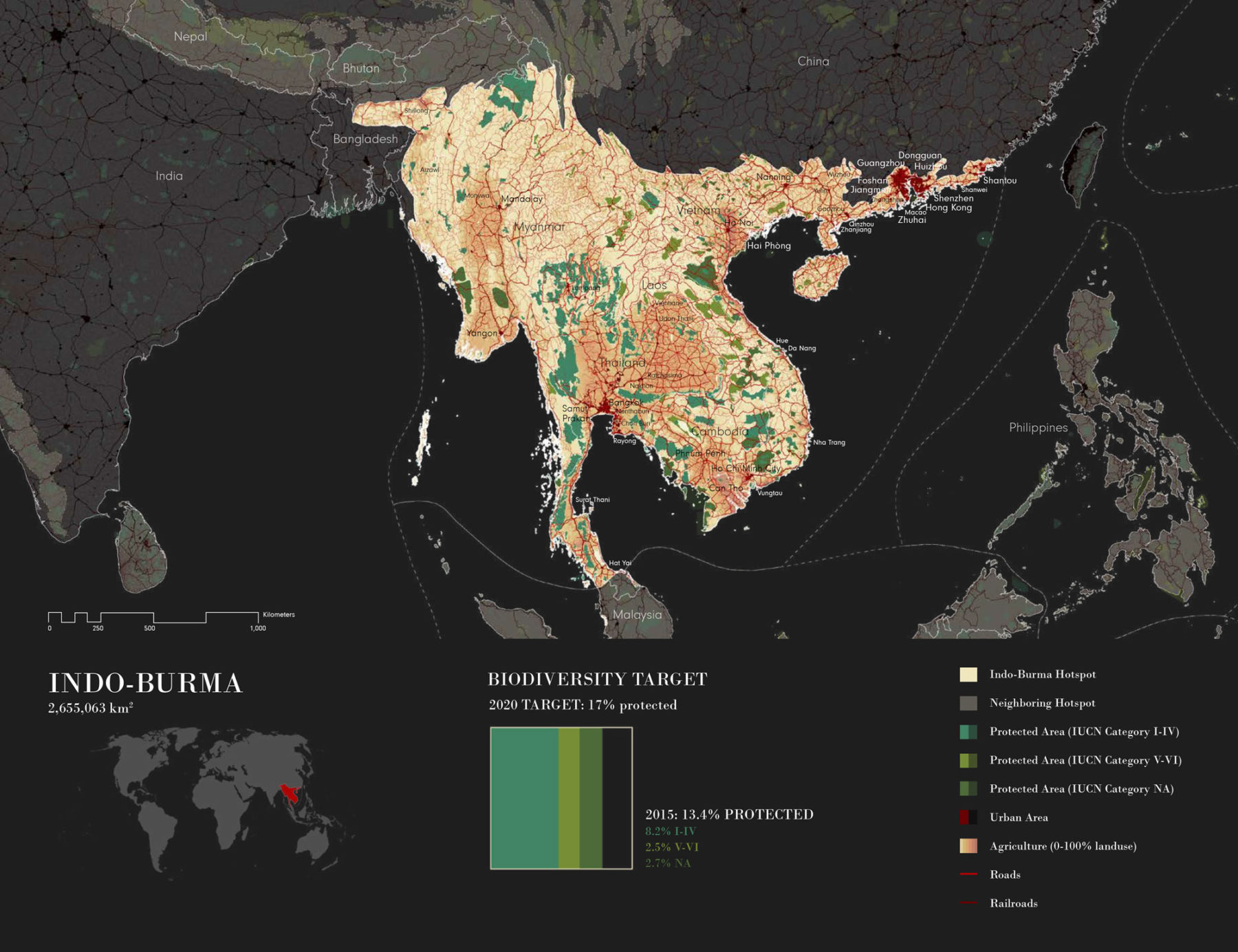

The Atlas for the End of the World, conceived by Richard Weller, ASLA, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, is one of the best sources for documenting our collective risk. Mapping 391 of the planet’s terrestrial eco-regions, this research identified 423 cities with a population of over 300,000 inhabitants situated within 36 biodiversity hotspots. Using data modelling from the Seto Lab at Yale University, the Atlas predicts that 383 of these cities—about 90 percent —will likely continue to expand into previously undisturbed habitats.

Biodiversity hotspot map of the Indo-Burma ecoregion / Atlas for the End of the World

When we assault the wild places that harbor so much biodiversity in the pursuit of development, we disregard a significant aspect of this biodiversity—the unseen domain of undocumented viruses and pathogens.

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 75 percent of emerging infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, meaning that they are transmitted to us through contact with animals. The initial emergence of many of these zoonotic diseases have been tracked to the parts of the world with the greatest biodiversity, both in the traditional and man-made sense. Traditional locations include tropical rainforests where biodiversity naturally occurs. Human-influenced conditions include places like bushmeat markets in Africa or the wet markets of Asia, where we are mixing trapped exotic animals with humans, often in astonishingly unsanitary conditions.

However, degraded habitats of any kind can create conditions for viruses to cross over, whether in Accra or Austin. The disruption of habitat to support our suburban lifestyle is bringing us closer to species with which we have rarely had contact. By infringing on these ecosystems, we reduce the natural barriers between humans and host species, creating ideal conditions for diseases to spread. These microbes are not naturally human pathogens. They become human pathogens because we offer them that opportunity.

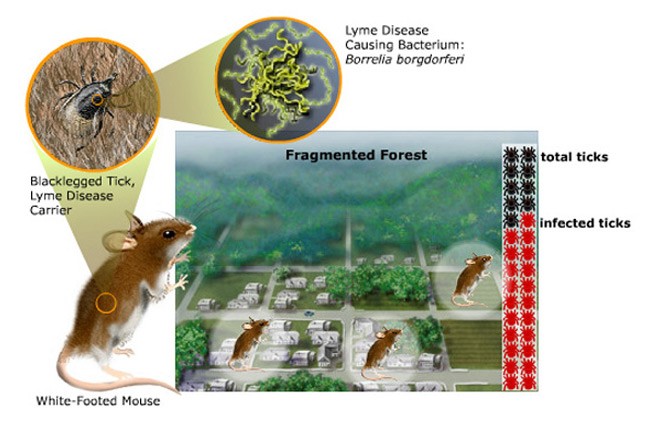

This is already evident in the fragmented forests of many American suburbs where development patterns have altered the natural cycle of the pathogen that causes Lyme disease. When humans live in close proximity to these disrupted ecosystems, they are more likely to get bitten by a tick carrying the Lyme bacteria. When biodiversity is reduced, these diluted systems allow for species like rodents and bats—some of the most likely to promote the transmission of pathogens—to thrive.

This essentially means that the more habitats we disturb, the more danger we are in by tapping into various virus reservoirs. COVID-19 is not the first disease to cross over from animal to human populations, but it is likely a harbinger of more mass pandemics and further disruptions to the global economy. The more densely we build, the more land we can conserve for nature to thrive, potentially reducing our risk of another pandemic from a novel virus.

Increase of infected tick populations in fragmented forests / National Science Foundation, Nicolle Rager Fuller

In the United States, over 50 percent of the population lives in suburbs, covering more land than the combined total of national and state parks. Our urbanization is ubiquitous and endangers more species than any other human activity.

In 1979, Portland, Oregon offered a pioneering solution with the creation of an Urban Growth Boundary (UGB). Devised by a 3-county, 24-city regional planning authority, the intent was to protect agricultural lands, encourage urban density, and limit unchecked sprawl.

Forty years into this experiment, Portland’s experience is a mixed bag of successes and missed opportunities. Investment in public transit and urban parks has certainly bolstered the city’s reputation as a leader in urban innovation, sustainability, and livability, with statistics to support its efforts.

On the other hand, two of Oregon’s fastest growing cities are situated just beyond the boundary’s jurisdiction, underscoring the limitations of the strategy. Again, inequity rears its ugly head, with higher prices within the UGB caused, in part, by an inability to deregulate Portland’s low density neighborhoods. This has driven much of the regional population further afield to find affordable housing in the form of suburban sprawl beyond the UGB’s dominion and into even more remote areas.

Another consideration that was overlooked when the original plan was established was the adequate protection of remnant habitat within the UGB. This lack of a regional plan for biodiversity protection has underscored the need for a more ecologically-focused, science-based approach to inform planning decisions.

Suburban development approaching agricultural land and remnant forest in Portland, Oregon / Google Earth

Unfortunately, anticipating outcomes of urbanization on species diversity is not as pervasive in urban planning agencies around the world as it should be. A lack of detailed modeling specific to individual regions and cities with clear recommendations for how to minimize ecological devastation is absent from planning policy around the world.

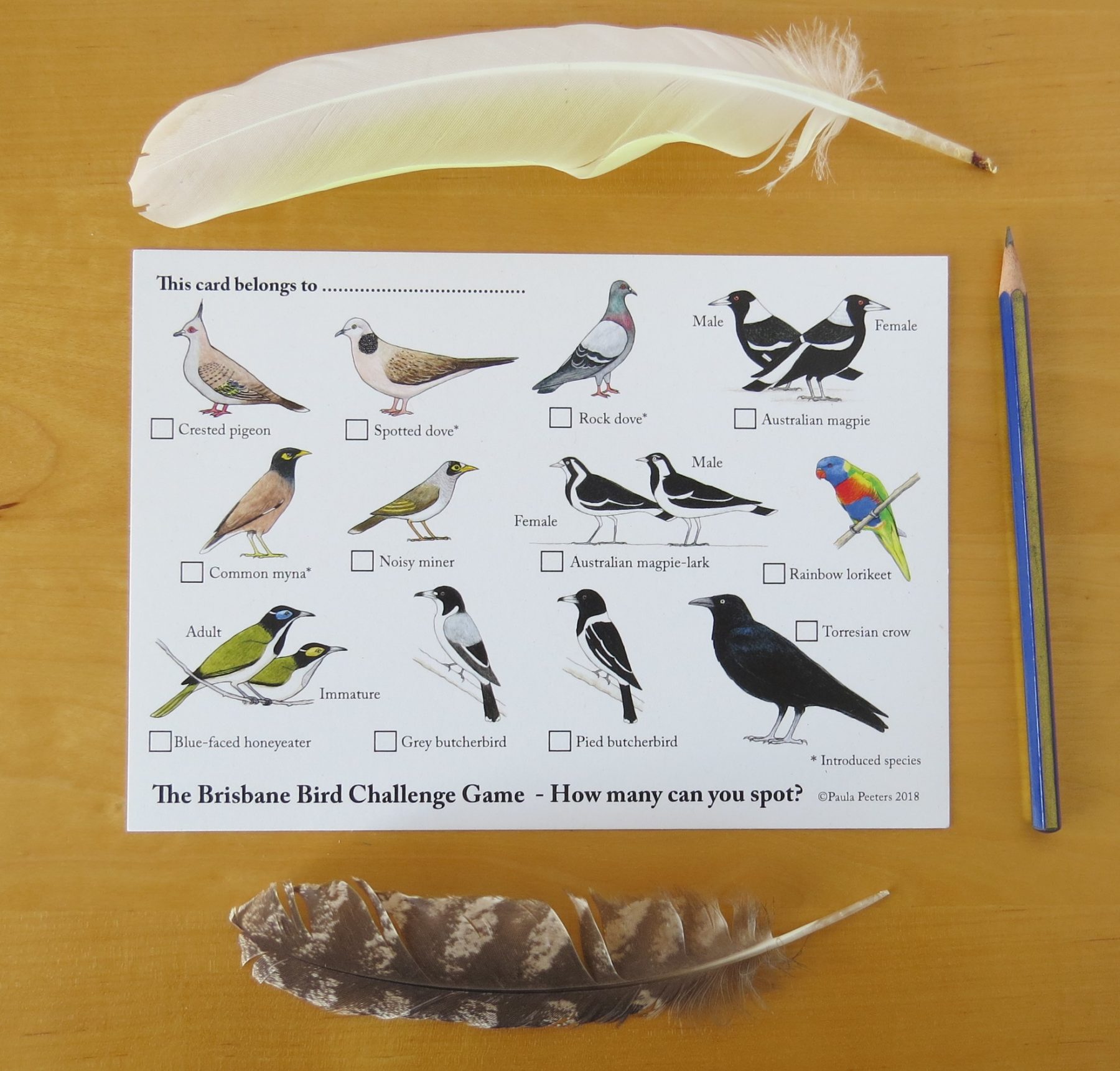

However, researchers in Brisbane, Australia have attempted to quantify which development style—concentrated urban intensity or suburban sprawl—has a greater ecological consequences. By measuring species distribution, the study predicted the effect on bird populations when adding nearly 85,000 new dwelling units in the city. Their results demonstrated that urban growth of any type reduces bird distributions overall, but compact development substantially slows these reductions.

Sensitive species particularly benefited from compact development because remnant habitats remained intact, with predominantly non-native species thriving in sprawling development conditions. These results suggest that cities with denser footprints—even if their suburbs offer abundant open space—would experience a steep decline in biodiversity.

This is a common outcome found in similar studies around the world that exhibit a comparable decline in the species richness of multiple taxa along the rural-urban gradient. Although biodiversity is lowest within the urban core, the trade-off of preserving as much remnant natural habitat as possible almost always results in greater regional biodiversity.

Common bird species in urban and suburban Brisbane, Australia / Paula Peeters

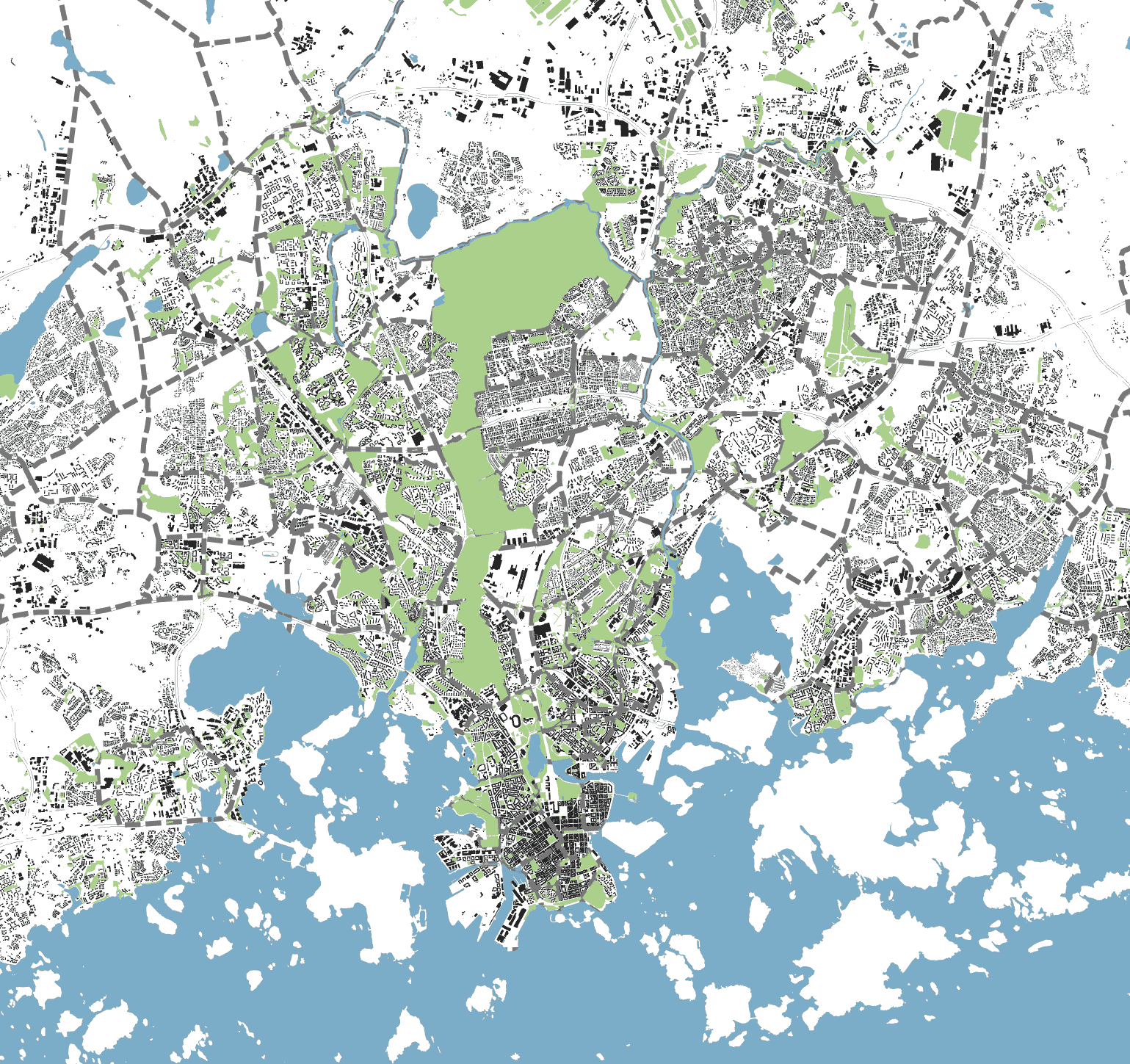

One of Europe’s fasted growing cities, Helsinki faces similar pressures for new housing and traffic connections as many other major metropolises. However, in Helsinki, geotechnical and topographic constraints, coupled with its 20th century expansion along two railway lines rather than a web of highways, created the base for its finger-like urban and landscape structure. Today, one-third of Helsinki’s land area is open space, 63 percent of which is contiguous urban forest.

In 2001, Finland established an open source National Biodiversity Database that compiles multiple data sets ranging from detailed environmental studies to observations of citizen scientists. This extraordinary access to information has allowed the city to measure numerous data points within various conservation area boundaries, including statistics related to the protection of individual sites and species.

Measured by several taxonomies, including vascular plants, birds, fungi, and pollinators, Helsinki has an unusually high biodiversity when compared to neighboring municipalities or to other temperate European cities and towns. Vascular plant species, for example, average over 350 species per square kilometer, as compared to Berlin and Vienna’s average of about 200 species. By embracing biodiversity within the structure of the city, not only is the importance of regional biodiversity codified into the general master plan, it is also embedded into the civic discourse of its citizens.

Figure-ground diagram of Helsinki’s green fingers / Schwarz Plan

When it comes to where the next virus might emerge, Wuhan isn’t really that different from Washington, D.C. If the American model of over-indulgent suburban sprawl is the benchmark for individual success, we all lose.

Now is the moment to put the health of the planet before American values of heaven on a half-acre. Land use policies in the United States have just as profound an impact on the rest of the world as any movie out of Hollywood.

If we shift American values toward embracing denser, cleaner, and more efficient cities that drive ecological conservation—instead of promoting sprawl as a panacea for our current predicament—that may very well be our greatest export to humanity.