Expressing a Regional Identity through China’s Sponge City Initiative

Sasaki

Sasaki

Nicknamed the “City of Springs” and with a modern-day name meaning south of the Ji River (a historic river now part of the Yellow River), Jinan’s identity is closely tied to its water resources. However, Jinan has expanded significantly beyond its historic moat and walls over the past century, complicating its relationship with its namesake waters both above and below the surface.

This post was co-written by landscape architect Yi-Ting Chou and former Sasaki employee Anthony Fettes

Following a wave of rapid urban expansion and significant land use changes in recent decades, water-related issues in the region have increased. These issues are intensified by the highly variable monsoonal precipitation regime, with nearly 90% of the annual precipitation occurring from May to October. As a consequence, many of the city’s signature springs have decreased in flow or dried up in recent decades. Yet while the flow of water from the ground has become increasingly intermittent, some areas of the city have seen a dramatic rise in flash flooding from more frequently intense rainfall events compounded by the city’s outdated stormwater infrastructure.

Recognizing that many of these water-related issues were associated with urbanization, in September 2015 the Chinese central government initiated its “sponge city” campaign starting with 16 cities—including Jinan—and expanding to over 20 provinces and 1000 projects in 2016. With the primary goal of restoring local hydrology using a systems-based approach, the “Sponge City” initiative also holds the potential to help increasingly generic cities express their regional identity.

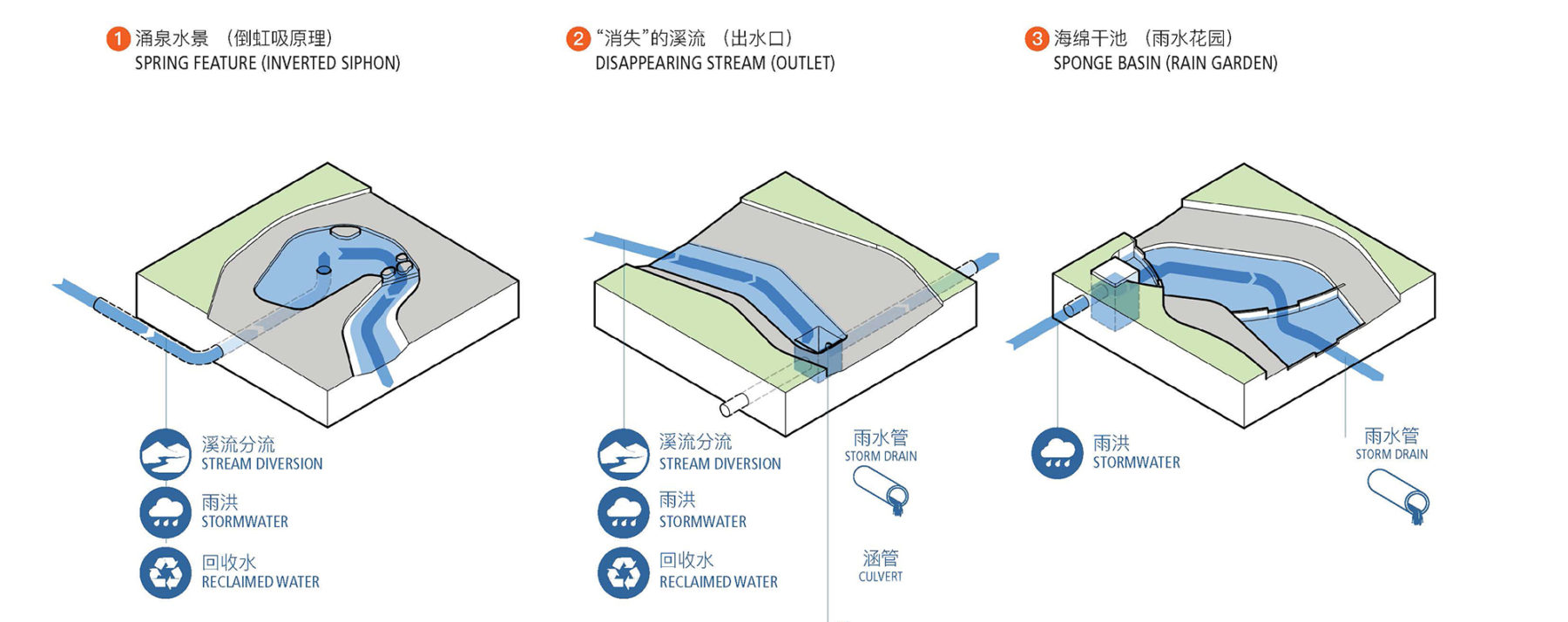

Pictured above, the landscape master plan for the new 3.2 km2 (1.2 mi2) Central Business District (CBD) of Jinan explores this potential through integrated landscape design as the city moves forward to transform this historic and culturally significant city into a regional hub for finance, logistics, and technological innovation. Located approximately 7 km east of the historic city center and the iconic springs, the new CBD area is situated slightly higher in elevation on the foothill dotted piedmont of the Taishan Mountains. With an estimated future population of 31,000 and gross floor area of nearly 10 million square meters, the proposed Master Plan for the new district presented a complex web of infrastructure in which existing waterways were destined to be rerouted, capped, and utilized as part of the new district’s stormwater infrastructure.

One waterway slated for covering was Dingjiazhuang Ditch. Early in the design process, efforts were made to maintain this existing 2 km (1.25 mi) drainage corridor, referencing successful stream daylighting and restoration projects from around the world. However, faced with multiple layers of underground infrastructure (soon to be constructed) including utility tunnels, underground streets, parking structures, retail, and subway lines, the density of this infrastructure made fully restoring the waterway a significant engineering challenge. Given the advanced phase of the CBD’s Master Plan, this approach was not considered a viable option despite the tremendous value for placemaking and proven ecological and water quality benefits.

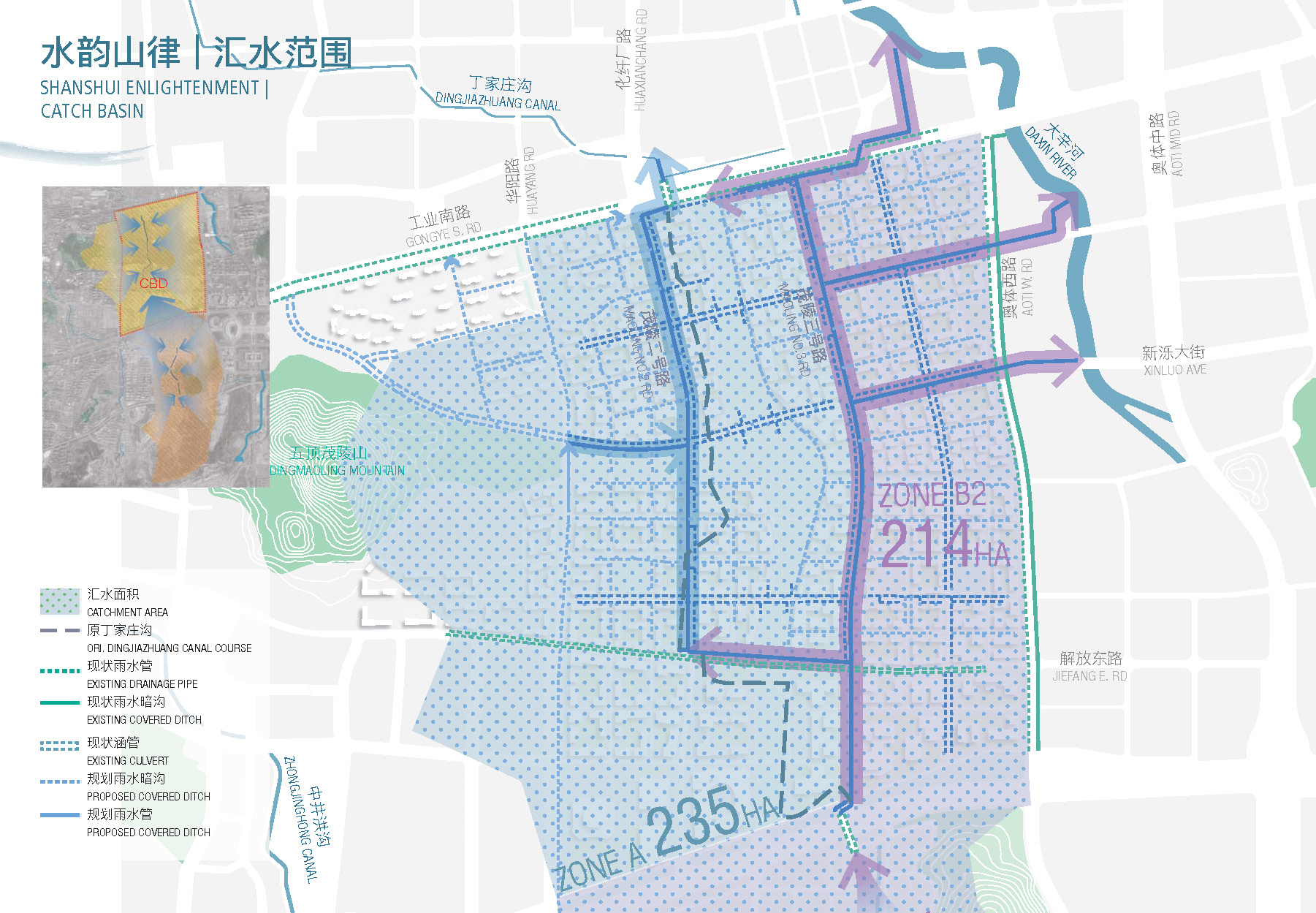

Determined to find a solution, our interdisciplinary design team estimated that the peak flow entering the site and increased surface runoff would far exceed the limited space beneath the seven proposed street crossings. Above all, safe and usable park space would need to be maintained in order for the concept to move forward. To resolve these challenges, a low-flow diversion was determined to be the only practical way of restoring a manageable base flow to the waterway. With this strategy, the team was able to establish several options early in the design process, ensuring that water would be a central and lasting feature of the design.

Inspired by the local geomorphology, the boldest design approach diverts a manageable portion of the seasonal base flow from Dingjiazhuang Ditch into the ribbon park, mimicking the form and function of ephemeral streams found throughout the area. With a similar source of inspiration, the most conservative option integrates a series of rain gardens that imply the form of the ephemeral streams. In this option a series of basins would intercept runoff from the surrounding development, promoting infiltration and groundwater recharge throughout the CBD.

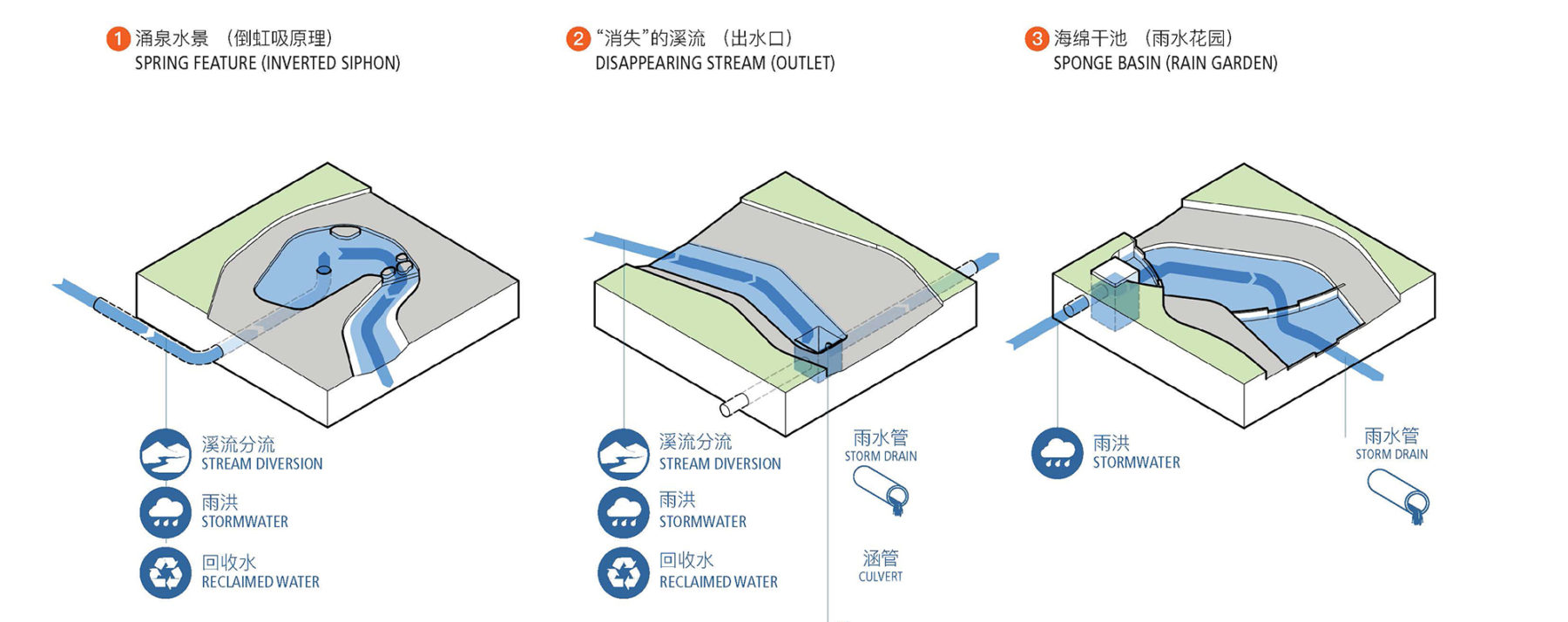

In the end, a hybrid option [pictured above] was chosen for its flexibility and overall expression of regional identity. Inspired by the karst geology of the Taishan Mountains to the south—the source of the city’s famed springs—the hybrid option integrates features resembling springs, disappearing streams, and ephemeral channels (rain gardens), as part of a comprehensive “Sponge City” approach to the site.

As the challenges of both seasonal drought and flash flooding increase in Jinan and throughout China, Sasaki’s integrated systems-based approach to “Sponge City” principles elevates the importance and relevance of interdisciplinary design solutions. Bringing together a team of landscape architects, ecologists, and engineers, the team was able to draw inspiration from the region’s climate, landscape, and vernacular design to propose scale and location appropriate solutions that are multi-functional—reducing flooding, improving water quality, and providing a recreational amenity to the new district.