Expanding Our Perceived Space Through Design

Sasaki

Sasaki

Trained as an ecologist and landscape architect, Tao Zhang, Sasaki Principal, ASLA, PLA, is active in the arena of ecological design, striving to bridge the gap between practice and science. Tao is an integral part of Sasaki’s strong international presence and has led and contributed to a number of award winning projects.

The article originally appeared in an interview between Tao Zhang and designverse.

“We strategically expanded the perceived waterfront space along Suzhou Creek into its urban fabric so that people would realize that the waterfront is a concept larger than its linear physical appearance. Here, design became a tool to help shape the public perception of the shared tangible environment,” begins Zhang.

Tao took a deep dive into landscape and urban design through some Sasaki projects, including Shanghai Suzhou Creek, Chengdu Panda Reserve, Denver International Airport Strategic Development, Zhangjiabang Park, Chicago Riverwalk, and Greenacre Park.

Tao Zhang shared his interest in “the juxtaposition and balance between urban fabric, architecture, and landscapes.” For instance, Central Park in New York is one of the most iconic landmarks in the world, surrounded by dense skyscrapers. Without Central Park, the skyscrapers probably wouldn’t outshine the skylines of some emerging metropolitan areas; by the same token, without the densely enclosed skyscrapers, Central Park is no more than a large man-made urban park. It is the juxtaposition, at once complementing and contradicting each other, that makes an iconic Manhattan scene, and a textbook case for numerous urban studies and design inspirations.

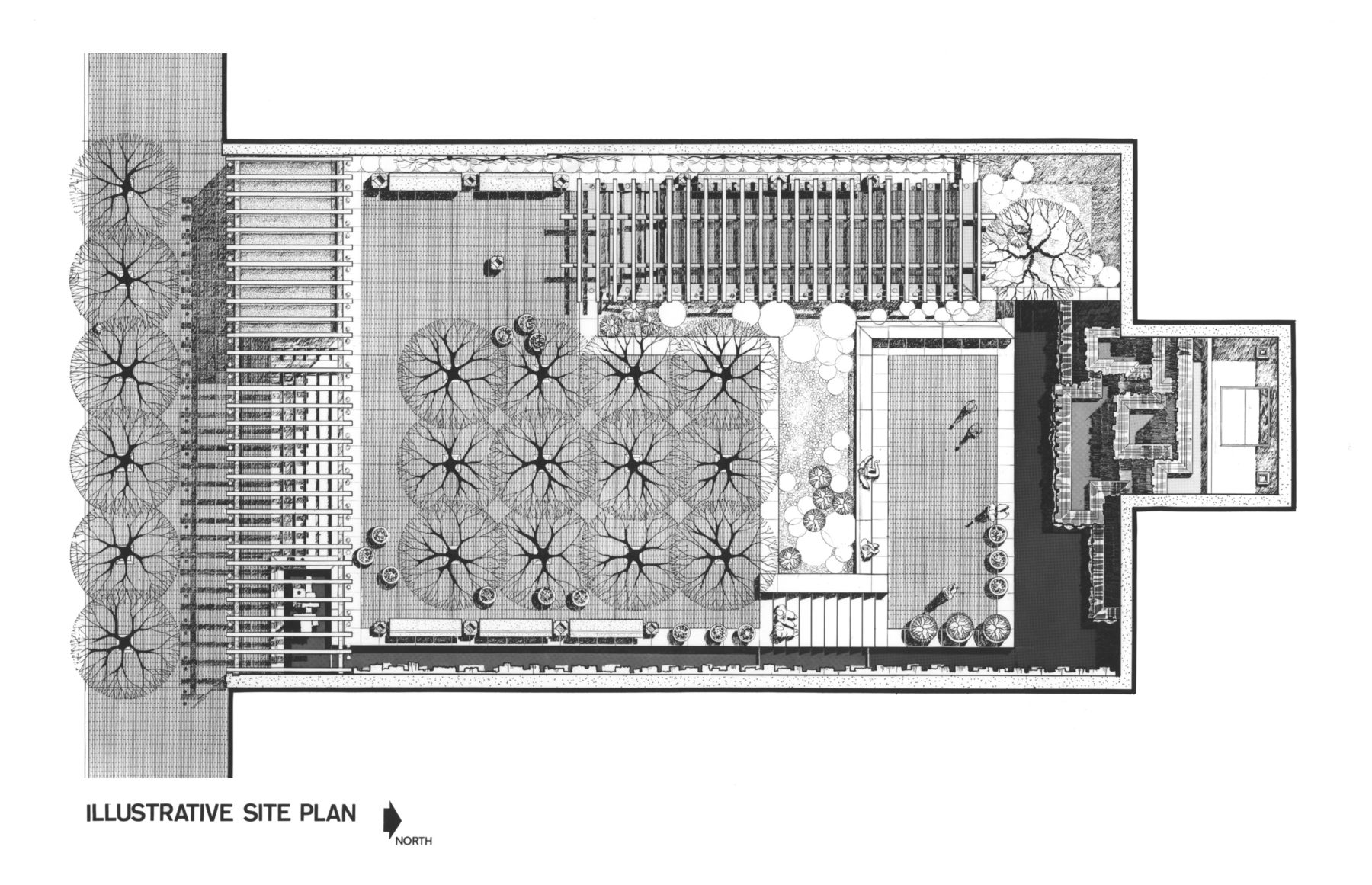

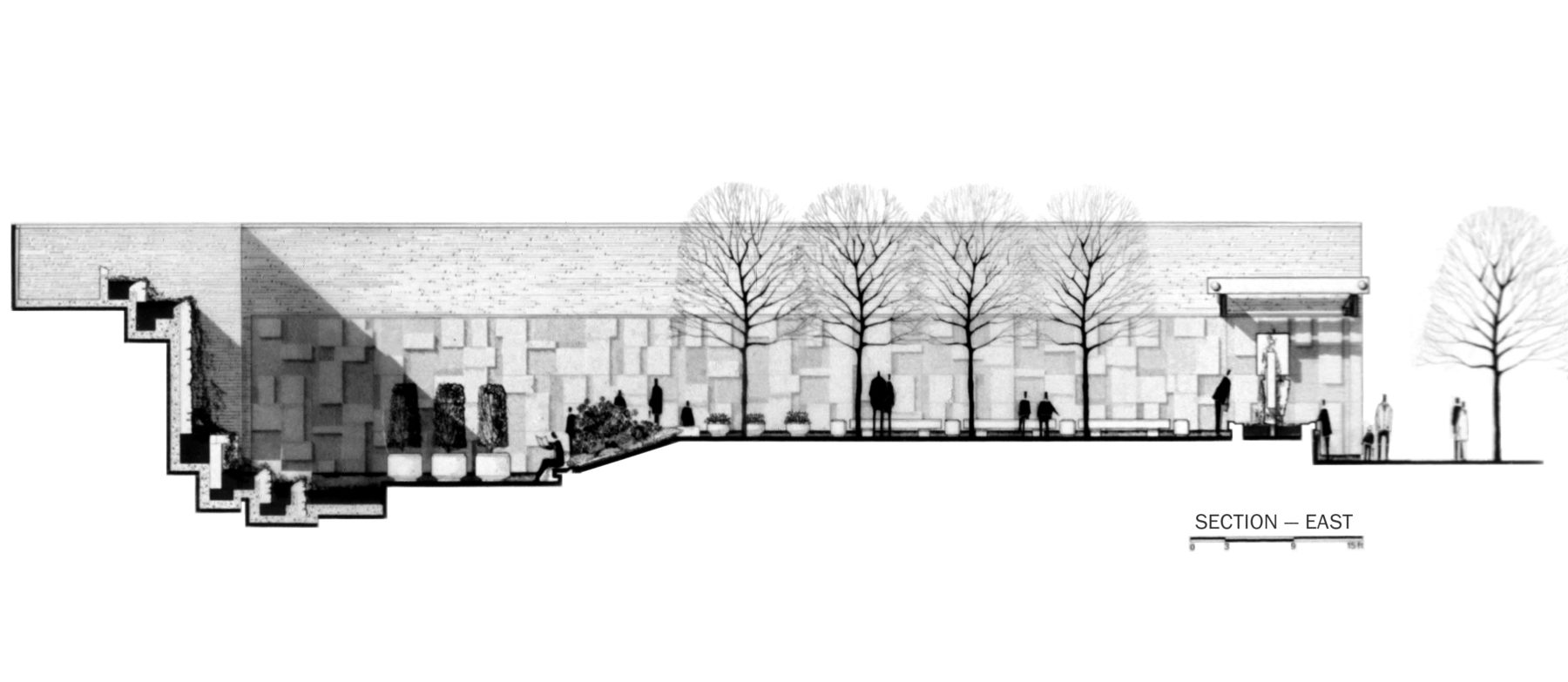

Tao further elaborated his understanding of the contrast and balance in this relationship: the principle is equally applicable at smaller and intimate scales, such as the nuanced relationship between a tiny piece of nature and the courtyard surrounding it. This inherent balance between architecture and landscape is well demonstrated in Japanese Zen gardens. A design touch as minimal as one small tree, a carefully positioned rock, even flickering light filtered through leaves can have a huge influence on the feeling of the space as a whole. Greenacre Park in New York – a Sasaki legacy project from the 1970s echoes this idea. As a pocket park in a dense neighborhood, it portrays one of the most critical juxtapositions between landscape and architecture in a contemporary urban environment. Nearly half century later, it is still a popular urban retreat, offering a nook for people to reflect, daydream, and take a break from the hustle and bustle of the city. However, cities today expand at a striking pace. Over-emphasis on FAR (Floor Area Ratio, an indicator of development density) and investment return has contributed to the neglect of beauty in this subtle balance.

verse editorial: Among the many award-winning projects you’ve led at Sasaki, which ones are your favorites? Or which project impressed you the most?

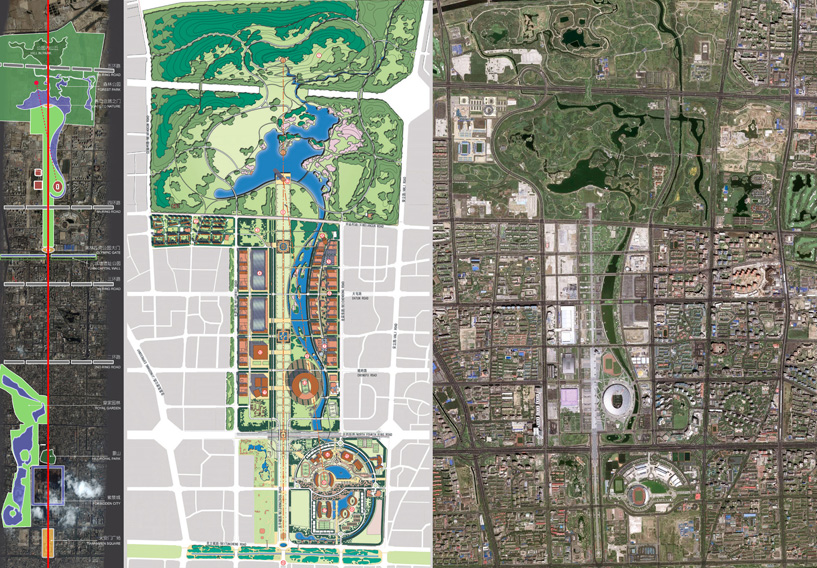

Tao Zhang: Every year, our projects are recognized by various national and international awards. So far, Sasaki has received more than 800 major awards since the beginning of the practice. One of my recent projects is the master plan for Chengdu Panda Reserve. It was a great opportunity to explore the balance between sustainable urban development and ecological protection. The giant panda is not only a symbol of international wildlife protection, but, as an ancient and endangered species, relies heavily on the help of scientific breeding and preservation to survive. After winning the international design competition, we also received the Honor Award in Analysis and Planning from the American Society of Landscape Architects’ Boston Chapter (BSLA), The Plan Award in Italy, and the MIPIM Asia award.

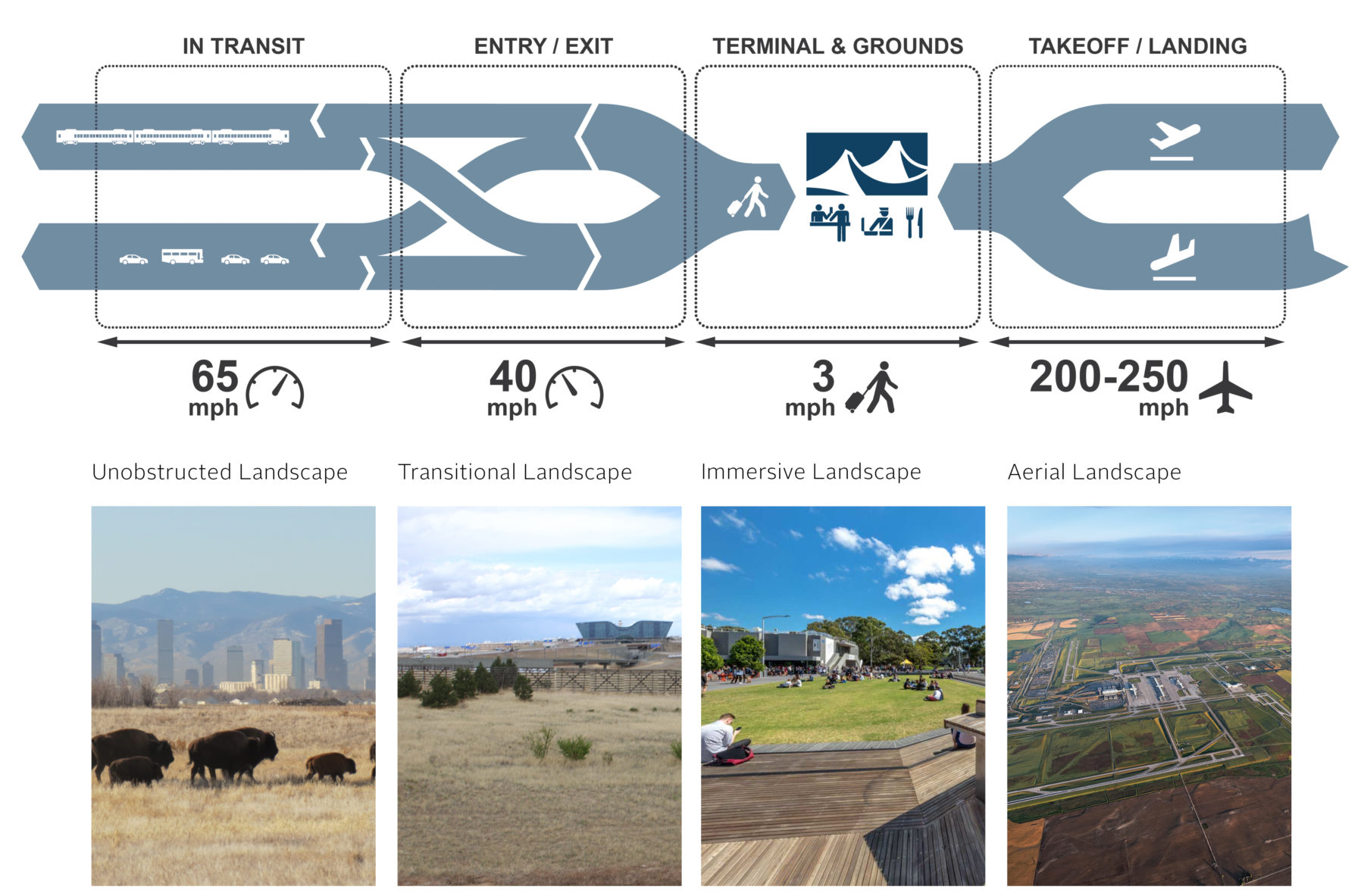

Another project I recently worked on is Denver International Airport (DEN)’s Strategic Development Plan. The 137-square-kilometer airport is the largest airport by land in the United States. The Plan transforms DEN into a multi-functional aerotropolis by enhancing its business, scientific research, and education functions as well as the overall landscape experience. The adjacent Arsenal Wildlife Refuge a former brownfields host a large number of wildlife species such as buffaloes, mule deer, and wolves. When you get off the plane and head for downtown, you’ll see buffaloes roaming freely in the prairie, which is a very unique experience. This project was also honored by BSLA in 2018.

And there’s Suzhou Creek—we were selected as the winning team for the international competition to redesign Suzhou Creek in Jing’an District, Shanghai. The project site spans more than 10 kilometers, along the Suzhou Creek throughout Jing’an district. We studied the history of both the Creek as well as the city of Shanghai to understand and mitigate the stigma it has in Shanghai residents’ memory. The project is a good example of how design not only changes physical environment, but also influences people’s mental maps. Suzhou Creek had been a black and stagnant body of water for decades, and its surrounding areas were once synonymous with shantytowns and the poor, until the environmental improvement led by the government in 2000s. The project involves copious issues beyond the given design scope, such as the public perception of the river. The significance of this project is to reposition the broader areas on both sides of the creek. Although it has been completed for nearly three years, it still left a deep impression on me.

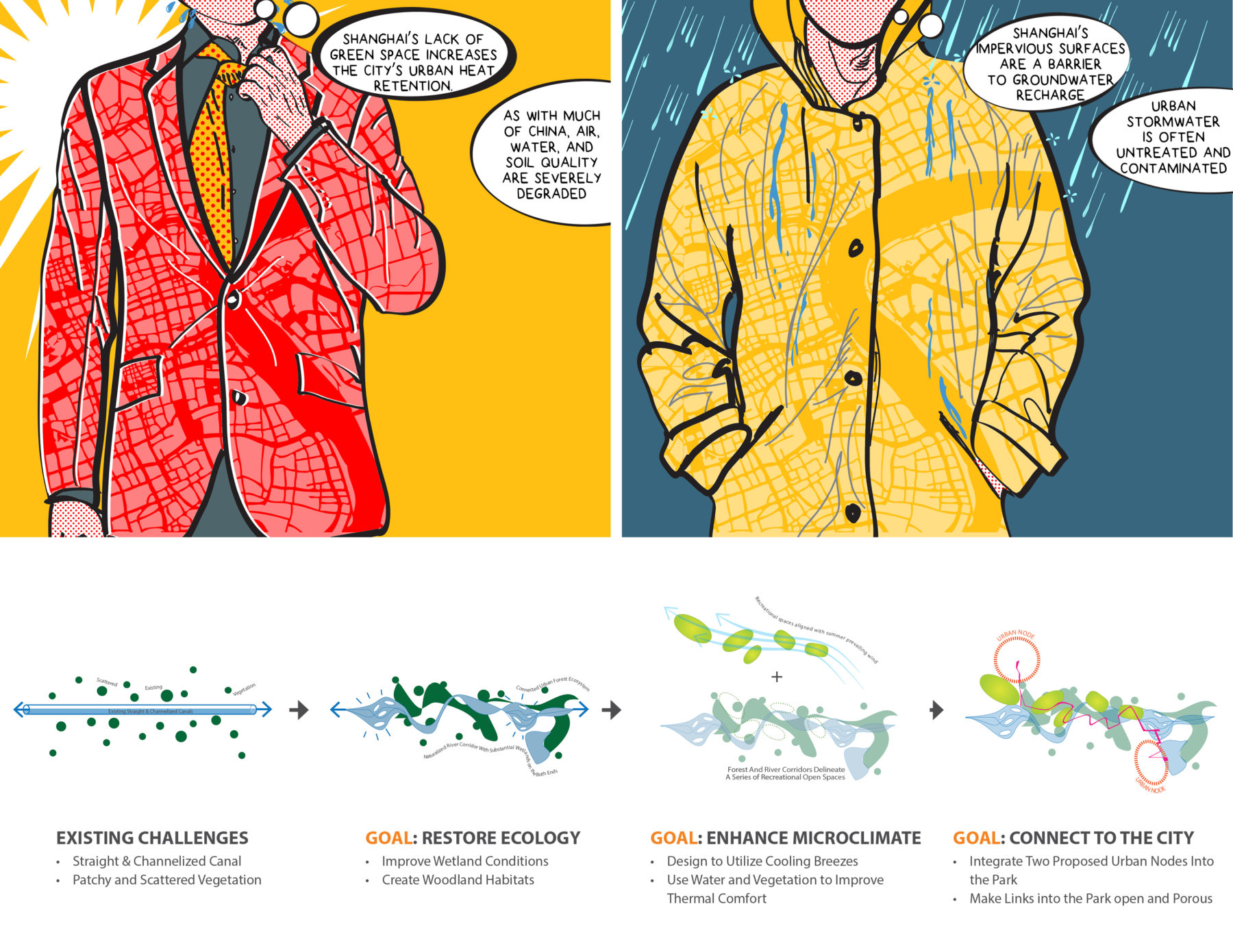

Zhangjiabang is the first of Shanghai’s eight planned “green wedges.” We were also selected as the winning team in the international competition. It is currently being implemented and will be further developed by local planning and design institutes. Soon, it will also become Shanghai SIPG Football Club’s new home field.

verse editorial: You emphasize the importance of aesthetics and creative expression in design, but at the same time seek design inspiration from scientific research and evidence. Can you elaborate on how you balance aesthetics and functionality in design?

Tao Zhang: Personality-wise, I think I’m more right-brained, so I eventually jumped into the art-related design industry after so many years of training in science. Today’s urban issues and design challenges cannot be solved by a single person or discipline anymore. We need multi-disciplinary collaboration and evidence-based practice. In the past, master designers could succeed with a strong single concept, from start to finish. But now, this doesn’t work, as our society is becoming more complex, with more urban, environmental and social problems. In addition, the internet has made infinite information increasingly accessible to all levels of social hierarchy. As landscape architects and urban designers, we create public space for the public, the ultimate end users. Therefore, our designs must be supported by rational facts and data. It doesn’t contradict how imaginative and creative you are. You have to be rooted in both.

Architects and related design fields used to make decisions subjectively and could ignore some challenges or uncertainty. On the one hand, this was a reflection of each designer’s personality or ego. On the other hand, the subjectivity could be due to a lack of information or technology to understand the complexity at the time. Today, the internet makes things different. Just because someone is a talented designer doesn’t mean they can ignore common sense. We need to be well-versed in science and be cognizant about the environment, ecology, wildlife habitat, air quality, and more. In addition, we also need to be informed by social science and better understand the needs of diverse populations, especially under-represented communities. These are all responsibilities that we have to undertake as designers.

At Sasaki we primarily work on the public realm. Its dynamic and ever-changing nature requires rational and logical analysis. But at the same time, design is a creative pursuit that should make life more interesting and people more engaging. It is important to integrate an evidence based approach with innovative and bold ideas.

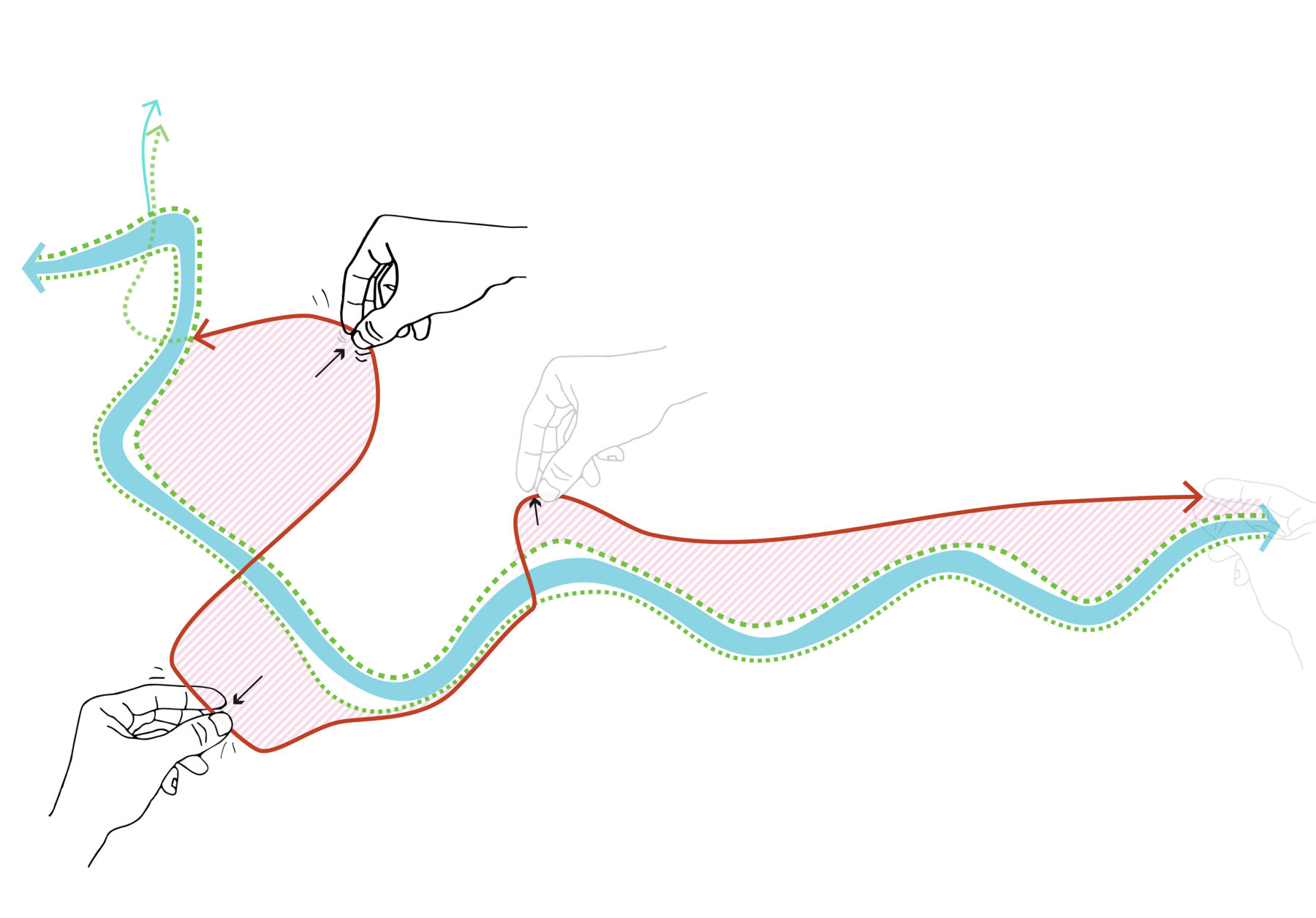

The design for Suzhou Creek is a good example of this aspiration. I tried to explain the complex design concept in a very simple diagram of hand pulling, modeled after my own hands when I sketched it. The diagram was instrumental in explaining the multifaceted design proposal to government officials and various stakeholders in a very compressed time frame. Our proposal for Suzhou Creek was not limited to the narrow physical scope along the water, which was the given premise of the competition. To us, the stigma of Suzhou Creek in local residents’ memory after so many years of neglect was the first challenge to overcome. The ultimate goal of the project was to reestablish Suzhou Creek as a waterfront asset to the city and its residents.

We also connected the Creek with other major urban nodes, such as Shanghai Railway Station. No one had realized before that the Railway Station was actually only a few minutes’ walk from Suzhou Creek until we started site analysis and inventory. So we took the liberty of expanding the design boundary to incorporate the railway station, an outdated infrastructure in the heart of the city waiting to be renovated. I believe our thinking outside the box and site boundaries was one of the factors that helped us win the project.

verse editorial: What is your favorite waterfront project?

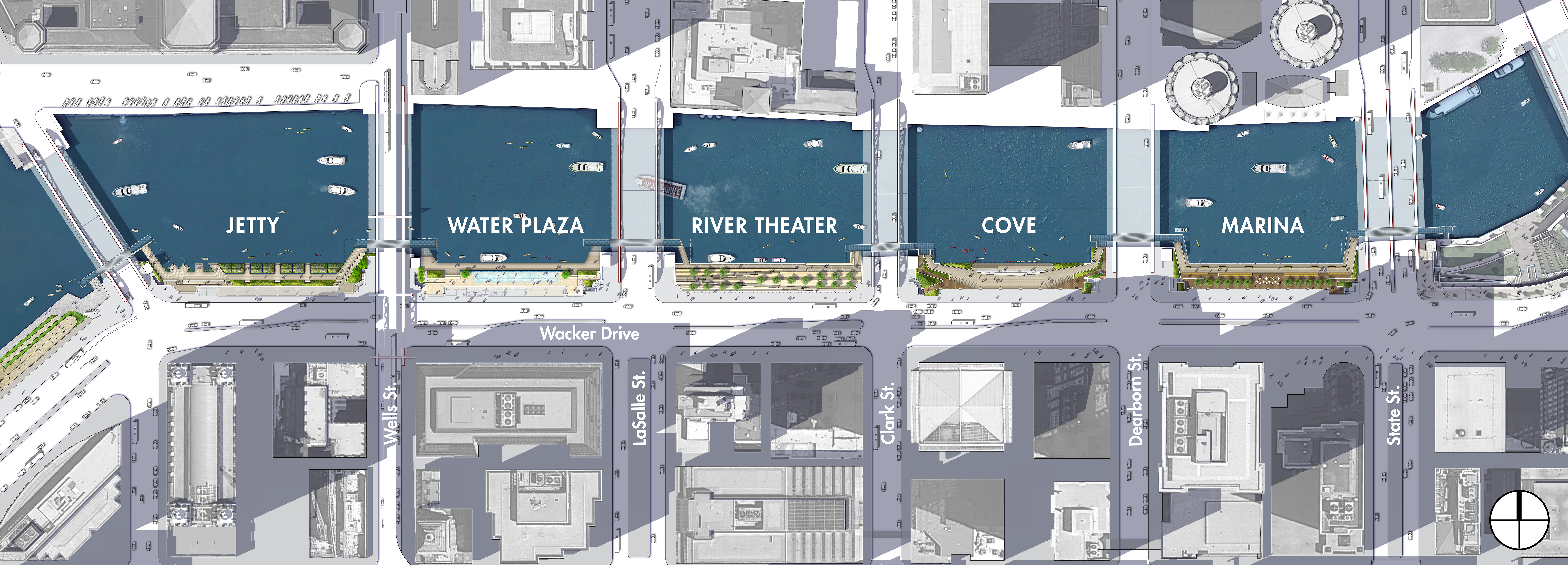

Tao Zhang: There are quite a few great waterfront projects that I like. To name one of our own, the newly completed Chicago Riverwalk won ASLA’s national design award last year. The previous waterfront embodied Chicago’s rich history of architecture and industry, but the space was stark and unfriendly. The challenge is relevant and similar to what many waterfronts in China are facing today. The embankment had an abrupt grade change of up to 8 meters. Our design transformed one of the coldest and least inviting spaces in the city into a popular destination for the public, especially in the summer. The project also successfully helped activate the adjacent high-density neighborhoods.

verse editorial: What is your favorite project that showcases the integration of landscape and architecture? Could you tell us more about it?

Tao Zhang: A great project that showcases the interplay of architecture, urban fabric and landscape space is Central Park in New York City. Central Park sits in sharp contrast to the densely-packed surrounding buildings. The juxtaposition creates tremendous value to the surrounding neighborhoods and all of Manhattan. Without Central Park, the surrounding skyscrapers are no more iconic than those in some emerging cities; by the same token, Central Park is no more than a picturesque large man-made park without its surrounding skyscrapers. It is the juxtaposition, at once complementing and contradicting each other, that makes an iconic Manhattan scene, and a textbook case for numerous urban studies and design inspirations.

Central Park, Photo from designverse

Golden Gate Park in San Francisco also reflects this strong contrast at a large scale. Outside its immediate border sits the dense city grid. The principle is equally applicable at smaller and intimate scales. For example, many contemporary Japanese gardens are very small and unassuming. But only the landscape or even a subtle stroke of nature completes the space.

Greenacre Park was designed by Sasaki in the 1970s, and is located in a prestigious neighborhood in Manhattan, New York. The client wanted to build a pocket park in a high-density city. Even though the park is private owned and managed, it’s open to the public. The park may not seem very novel today, but it’s still a popular destination and oasis amidst busy city life in New York.

verse editorial: In your opinion, what makes a good landscape design?

Tao Zhang: A good landscape design must stand the test of time, professional review, and the public acceptance. Such a space can balance the relationship between individuals’ needs, societal concerns, and the natural environment. Nowadays, there’s no shortage of high-quality spaces that are well-constructed using good materials and cutting edge technologies, but some of them do not take into account diverse social groups and communities. From a social perspective, a designed space should be mindful of all groups, including marginalized ones. From an environmental point of view, a landscape design should serve multi purposes, not just showcase a city’s economic power and wealth.

Personally, my favorite landscape designs are self-evolving and not too rigid. No matter the social status and physical condition, everyone should feel welcomed and empowered to enter and engage with the space. In terms of environmental challenges, I hope that landscape can play an educational role, even if the design doesn’t have significant direct impact on issues such as air quality or habitat degradation. For example, when kids come to play, a landscape that collects and repurposes stormwater can educate them about the natural water cycle. These small elements indicate how genuine and mindful of the environment a designer is.

verse editorial: Showcasing great projects is always beneficial. From a brand perspective, how do past projects help build Sasaki’s international reputation?

Tao Zhang: We are very proud of Sasaki’s strong reputation in the industry, and I am very grateful that I have spent my full career here. In China, we became well-known after winning the first prize in both the Beijing Olympics Urban Design Competition and Landscape Design Competition in the early 2000s. Beijing Olympics was one of the few first projects we did in China that helped establish our brand in China.

verse editorial:In your opinion, what opportunities should the design industry pursue in the future?

Tao Zhang: The quality of architecture and interior design in China cannot be underestimated. Emerging Chinese architects are winning numerous awards across the world. The ideas, design, and construction quality are consistently great. China’s infrastructure investment and development is an envy of many countries around the world. However, China is relatively late to start paying attention to public spaces and landscapes in cities. People are gradually realizing that architecture is not the only factor that dictates the image of a city. The neglected public spaces between buildings are some of the most potent places in the city where landscape design can play a very critical role, even if it’s as minimal as the paving pattern or a few trees. These undefined spaces hold huge potential for improvement of living quality of the cities.

verse editorial:How will technology change the industry in an increasingly diverse society?

Tao Zhang: technological advancement (in communication) has always been related to the problem of human loneliness. For example, more people prefer to read short articles and fragmented information on their phones, rather than take time to digest a full book. I see this as a reflection of anxiety and loneliness in modern life. Technology makes communication between people quicker and easier, yet ironically, makes people feel increasingly isolated. It shows how important human interaction and relationships are.

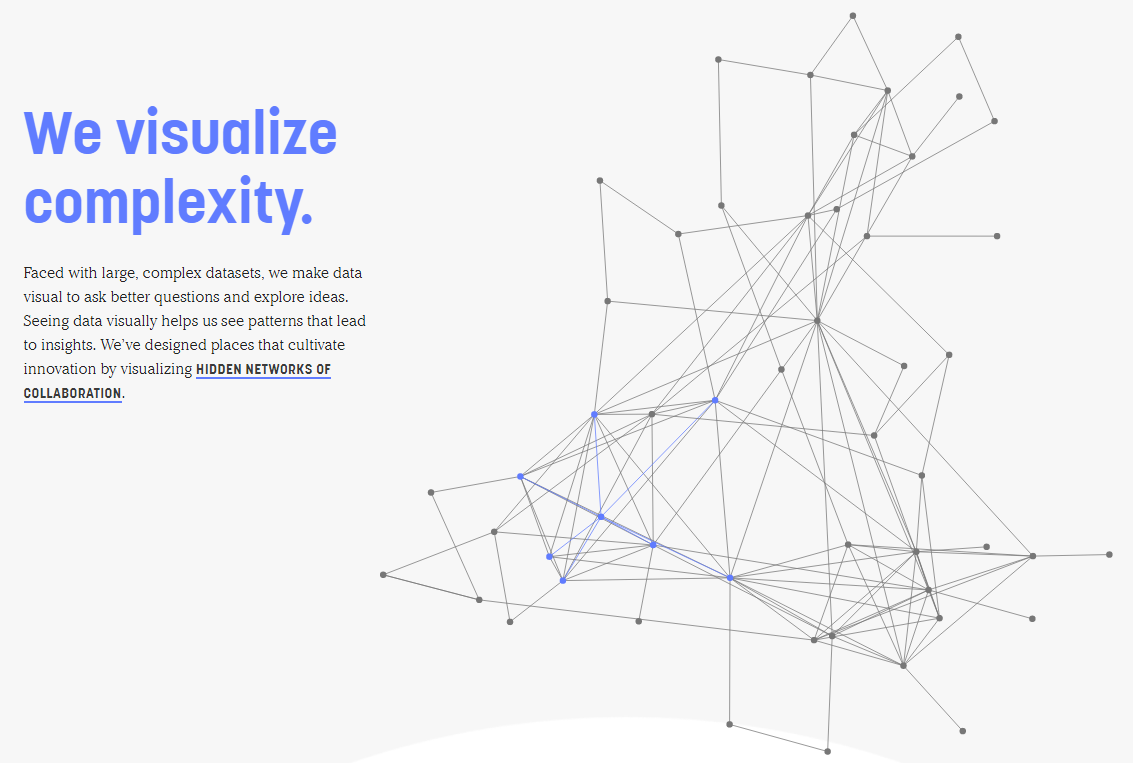

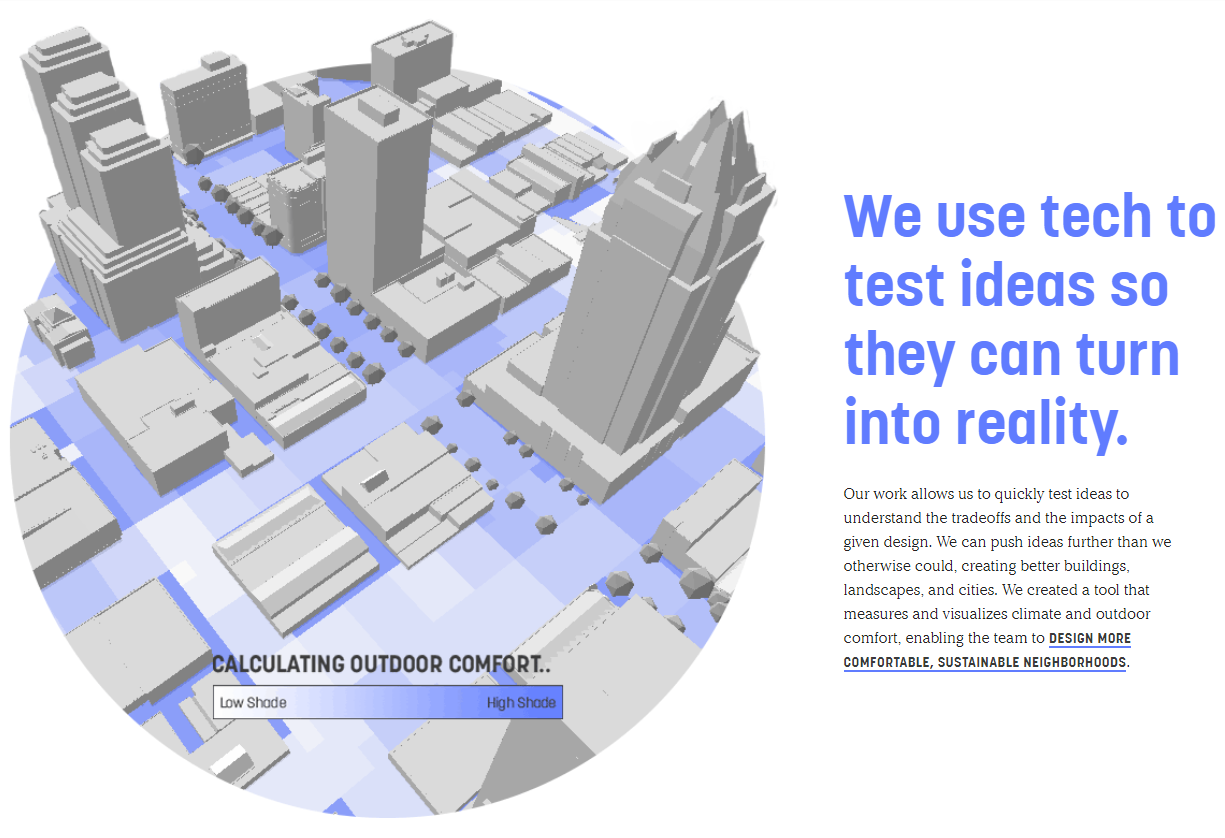

In terms of its application in our industry, technology can help people detect and reveal phenomena and patterns that are otherwise difficult for the human brain to process due to overwhelming amount of data. For example, Sasaki Strategies, a unique team in our company comprised of designers, software engineers, and even mathematicians, utilizes big data and new technology to precisely identify problems and create solutions to facilitate design. When we do urban design or campus planning there are tens of thousands of students at each university, presenting a complex web of dynamic interactions and relationships at the spatial and temporal scales, such as students’ activities, their curriculum and the occupancy of academic buildings. This intricate complexity can amplify by the thousands across the campus. They can’t be captured on paper in the traditional planning exercise. But thanks to big data and digital technology, we can quickly and accurately visualize the pattern in the complexity and offer insights to guide our design. “Smart cities” is not an empty term. A campus with thousands of people needs good technology to facilitate design and management. I believe that AI will help us continually improve our ability to create solutions in the future.

Sasaki Strategies also enriches design expression through VR, AR, and other visualization technologies. Technology can’t replace design, but it can elevate it, making it more accountable, accurate, and effective.