China’s Urban Revival: Lessons Learned

Urban renewal in China has been interwoven with its unprecedentedly swift urbanization over the past forty years. Sasaki's Dou Zhang and Ming-Jen Hsueh reflect on the rapid pace of change and lessons learned.

Sasaki

Sasaki

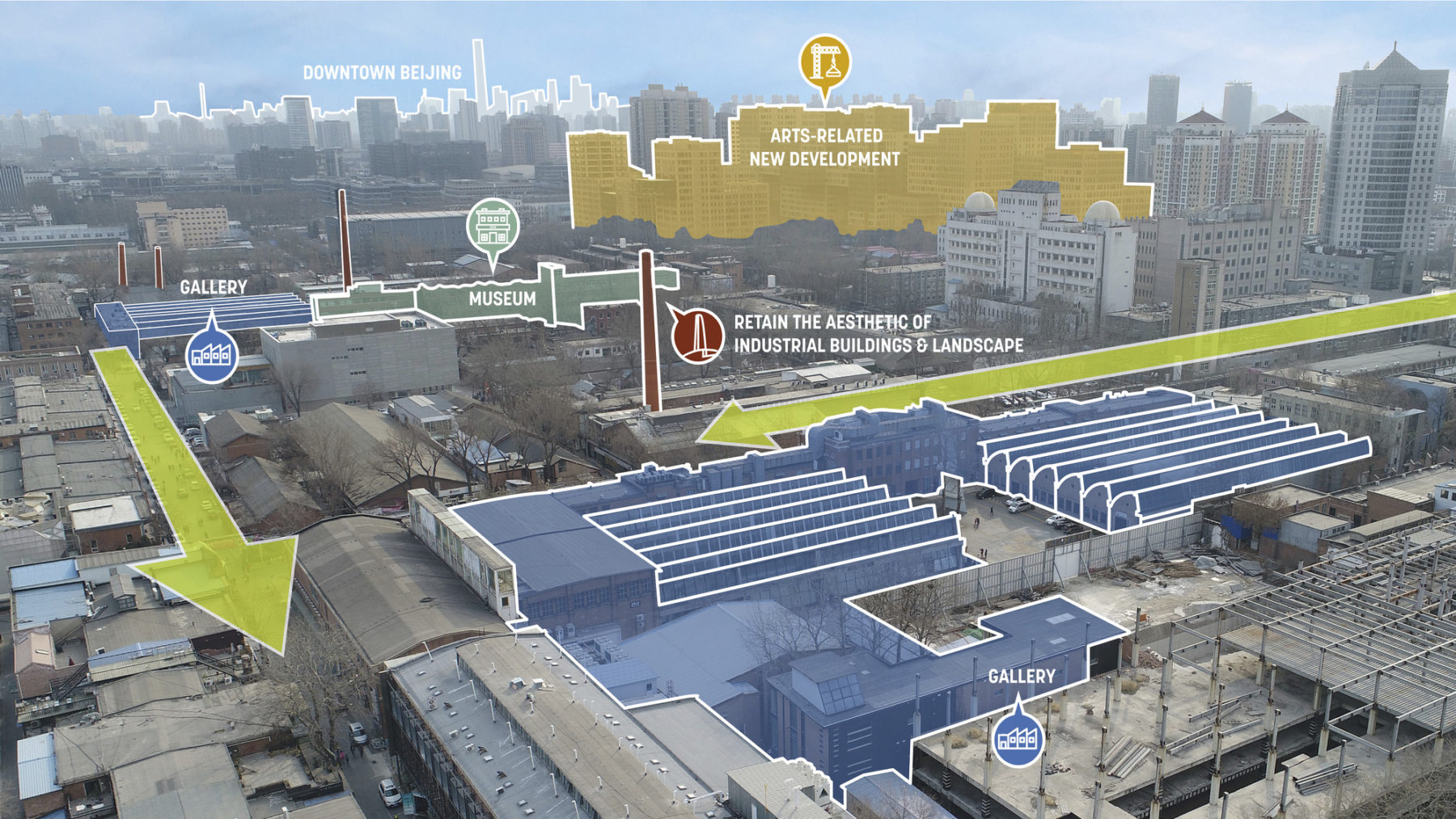

The 798 Arts Zone is wedged into 148 acres on the northeast corner of Beijing, where artists and creative tenants began to gravitate in the late 1990s

Before its evolution into a more open economy, China’s state-owned factories were identified by number. In Beijing, factory 798 and others around it once made weapons components. Today, they are the epicenter of China’s emerging modern art community. Working with a Belgian philanthropist who owns one of the world’s largest collections of contemporary Chinese art, Sasaki created a vision plan for the 798 Arts District that sought to solidify its role as a major force in China’s arts scene.

Abandoned factory buildings have been transformed to new museums, galleries, and cafes. Fallow fields and hidden courtyards are re-emerging as settings for outdoor sculpture, fashion shows, and other events. What began as a small collection of studio and other work spaces has now evolved into the third most visited destination in Beijing, after the Forbidden City and the Great Wall.

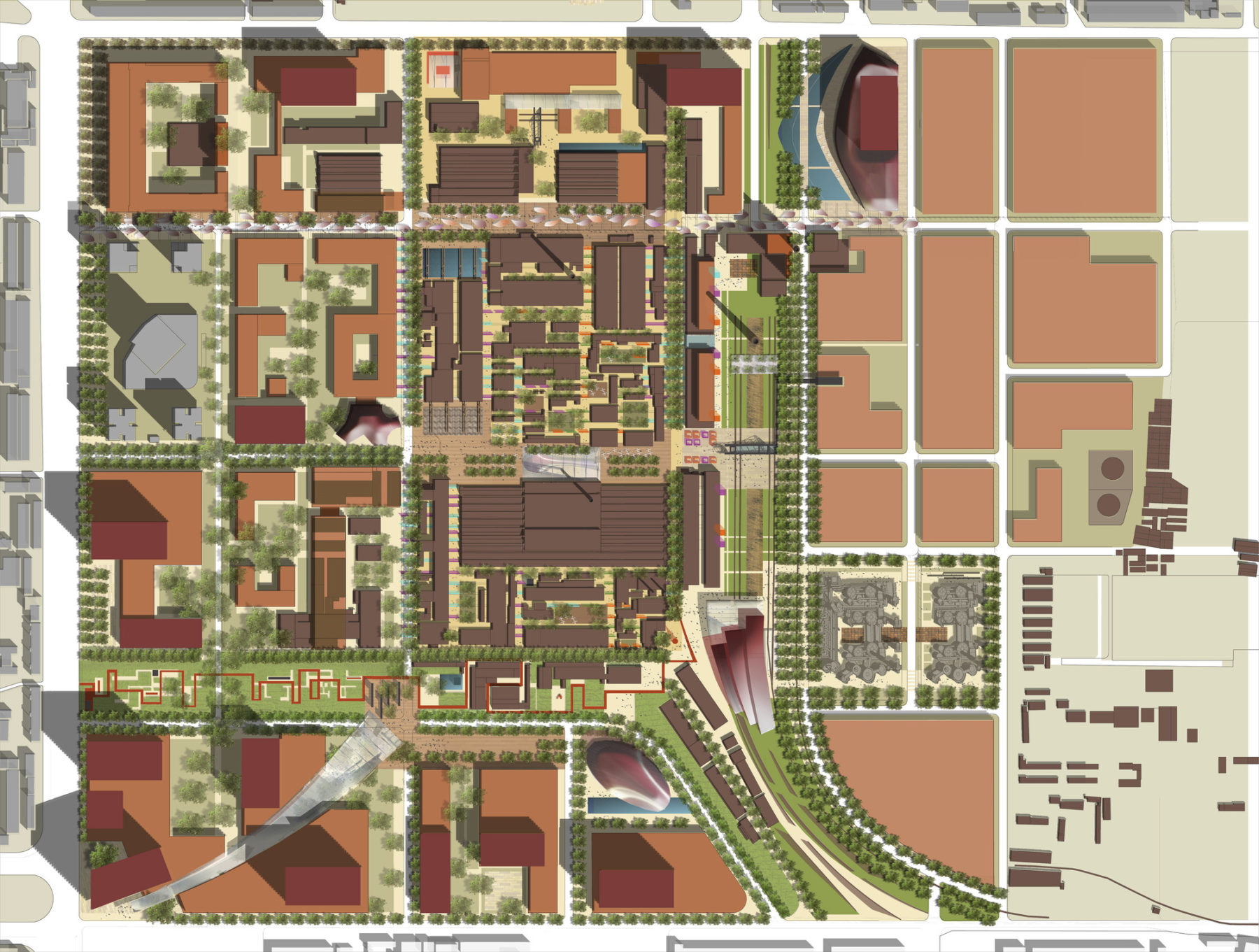

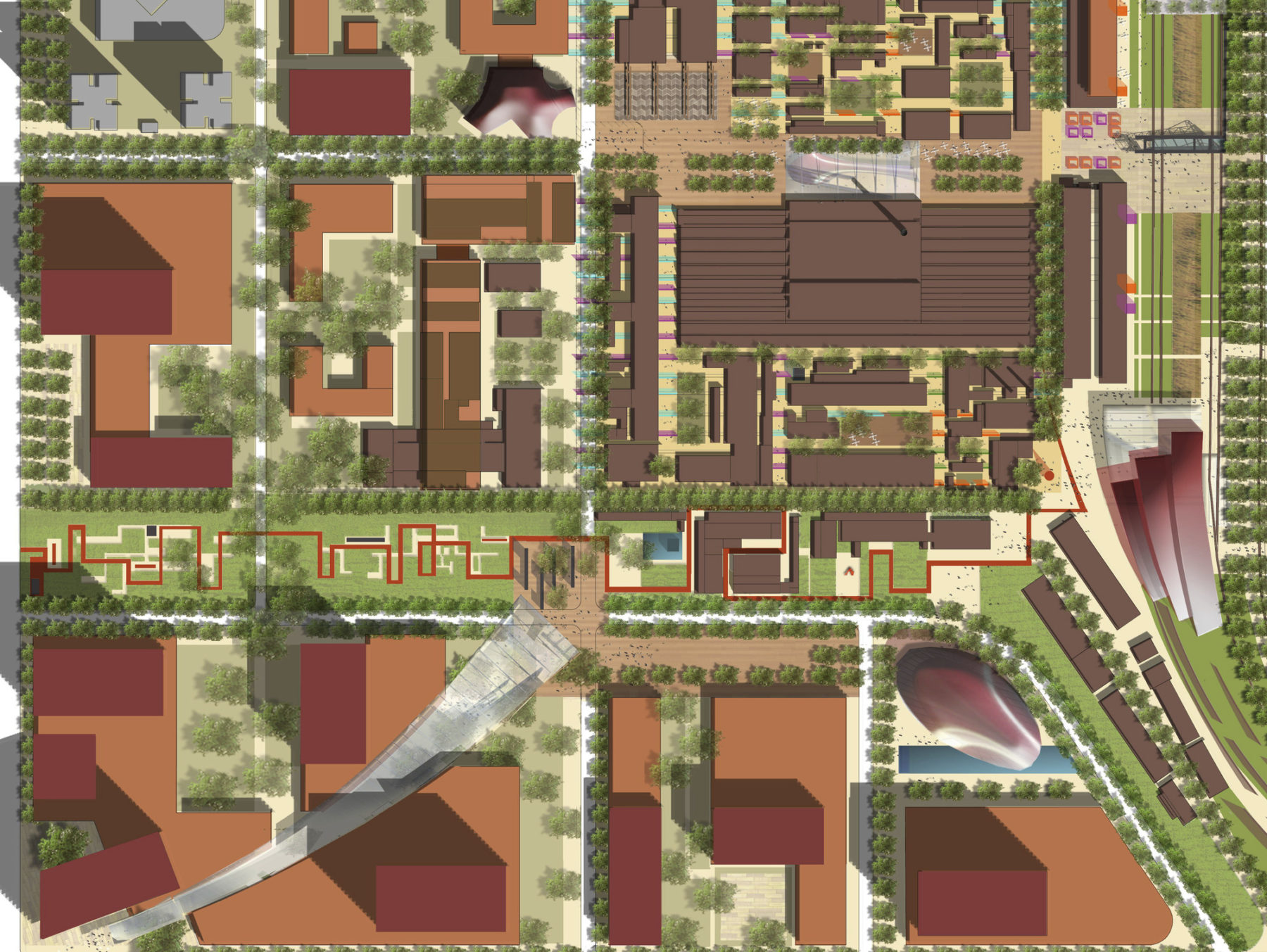

In the district’s core, the focus was on adaptive reuse of historic factories

On the periphery of the site, empty lots were an opportunity for new development

South Arts Square, a pedestrian core

Empty buildings are transformed into art galleries

In 2004, the district, already a haven for budding artists, faced destruction in the name of progress. The government considered the 50-year-old East German designed factory buildings as a low density waste of space in a city that needed to build vertically. Although these factory buildings are what give the district its unique architectural aesthetic, Beijing is a metropolis that values its blend of rich ancient history and contemporary architecture, but tends to ignore its mid-century industrialism. Seeing the potential long-term value of the district, Sasaki and client Urbis Development worked together to create a vision plan that would emphasize the district’s modern bohemian style and integrate its unique architecture and industrial elements, transforming 798 into one of Beijing’s most distinctive neighborhoods.

Industrail remnants act as dynamic structural features

An art installation adds color to the remains of a 1950s-era weapons factory, now home to museums, galleries, and other event spaces

In 2015, the Goethe Institut China opened an event space used for cultural exchanges, strengthening cultural ties between China and Germany

Pace Gallery Beijing hosts Yin Xiuzhen’s exhibition “Back to the end”

Theater complex

Industrail remnants act as dynamic structural features

An art installation adds color to the remains of a 1950s-era weapons factory, now home to museums, galleries, and other event spaces

In 2015, the Goethe Institut China opened an event space used for cultural exchanges, strengthening cultural ties between China and Germany

Pace Gallery Beijing hosts Yin Xiuzhen’s exhibition “Back to the end”

Theater complex

Outdoor plazas and streets are often used for fashion shows and large-art installations

The district is home to several festivals and events which activate the renewed spaces

A proposed arts school intends to infuse the district with fresh talent and ideas

As 798 continues to face pressure from the fast-paced growth of adjacent development, preserving the character and spirit of the district while infusing it with additional revenue-generating programs was a key component of the vision plan. Sasaki’s work emphasizes the arts as a central theme for the district; retains the essential qualities of the historic industrial aesthetic; develops strategies to make the district more visible and connected to the city; and encourages a wide variety of arts-related and contemporary uses to ensure a vibrant and dynamic district. To achieve this, the plan looks beyond simply preserving the existing factory buildings as static museums and galleries. Creative industries such as media, advertising, architecture, fashion design, animation, and software design ensure that the district will sustainably regenerate itself with new ideas. Additional new uses included a major museum at the center of the district—the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art—and a mix of additional exhibition space, galleries, theatres, retail, restaurants, entertainment venues, hotels, conference facilities, and parks and plazas for outdoor performances and sculptural displays. Other relics on the site, including a gasworks, railroad, and overhead cranes, were preserved to contribute to the district’s industrial aesthetic. Narrow streets alleyways become pedestrian-centric courtyards, corridors, and passageways that protect the district from the traffic congestion that is characteristic of Beijing. The result is a framework for 798 to continue to evolve, and transforming it into one of the world’s most important cultural districts.

798 Arts District draws millions of visitors each year

The district’s core focuses on adaptively reusing historic factories

Outdoor installations add interest to pedestrian walkways

For more information contact Michael Grove.