Think Big: Public Engagement

Digging into scenario planning and exploring questions about how to field community input

Sasaki

Sasaki

Today, the United States is investing the most it ever has in infrastructure and capital improvement projects at any time since the Marshall Plan, when America fueled the reconstruction of European economies in the aftermath of World War II. But unless this historic investment occurs efficiently and effectively, it will not only fall short of our expectations, but in fact lead to bigger, more expensive problems over time.

Many hoped that the massive infrastructure spending over the past several years would do more than create short-lived construction jobs by stimulating activity in the private sector to improve the nation’s economic health. But taxpayer expectations—which were uniformed to begin with—are largely unsatisfied. In the frantic rush to solve big problems, our nation has neglected the most critical component of any successful solution: a plan. The economic gain created by federal stimulus dollars has had little long-term value because little or no planning has been done to think strategically about how and where these investments should occur.

This is evidenced by the fact that at a time when the rest of the world is experiencing rapid urbanization, our nation continues to struggle with a trend in the opposite direction: shrinking cities. This phenomenon finds its roots in the 1956 Interstate Highway Act, which has proved to be the single largest force in shaping the development of urban centers in the US. The highway program, which was intended to improve access to our great cities, also made it easier to sprawl outside of our urban confines. Once-thriving industrial cities like Detroit and St. Louis have seen more than 60% of their populations leave since 1950. The list of 36 US cities that have seen a population decrease of 20% or more over that same time period also includes places like Boston and Washington, DC.

Neglecting planning today is hugely egregious because, at the forefront of the discipline, there are innovations that have rendered the process more efficient and effective than ever before. Gone are the days of garden cities and urban renewal which assumed good planning can only occur on virgin or cleared land. Today, good planning is defined by strategies that integrate a complex spectrum of social, economic, and environmental sustainability goals, united in a common vision shared by an equally complex spectrum of stakeholders. Planning must be transformational in order to be effective—and, today, it can be with the introduction of new technologies that are making the profession of planning more relevant than ever before.

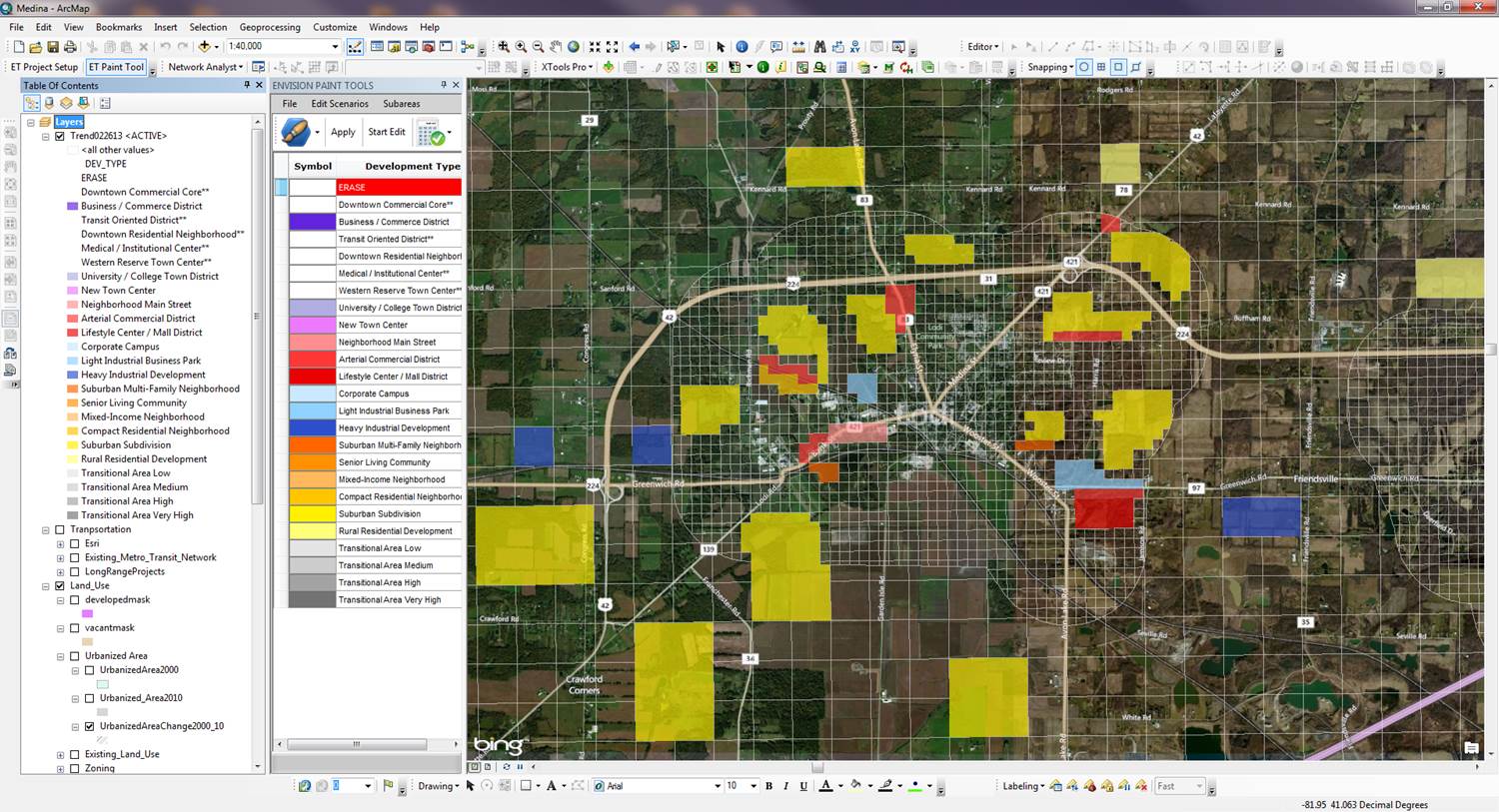

The power of these technologies lies in their ability to provide immediate feedback with simultaneous measurement of any quantifiable impact metric, including traffic generation, fiscal impact, water/sewer demand, and design and zoning considerations. This enables the planning process to dynamically test a range of scenarios, taking into account the impacts of identified variables. By providing this rapid feedback on the consequences of decisions, the modeling allows communities to be directly engaged in an innovative, dynamic planning process. Social media is also playing an increasing role in the planning world, engaging a wider audience in facilitating a productive discussion about their collective future.

Modeling Interface

With this in mind, the federal government introduced the HUD Sustainable Community Challenge Grant program in 2010. For the first time in history, this program created a collaboration between the HUD, DOT, and EPA offices by placing emphasis on planning as a tool to link infrastructure spending decisions to key outcomes such as economic development, social equity, and environmental sustainability.

Compared with roughly $800 billion included in the federal stimulus package, the $150 million allocated for the HUD program seems rather modest. However, the value of this investment in planning cannot be understated and the timing has been critical. Case in point: in Somerville, Massachusetts, a $1 billion transit investment is underway—the first major transit extension project in Boston in over 25 years—in a city that has never completed a comprehensive plan. Fortunately, Somerville sought a HUD grant to consider long-term sustainable growth issues related to the transit project: job creation, transit-oriented development, and affordable housing. This is a prime example of how good planning can instill a sense of values and priorities to manage expectations and make smart investments in our collective future.

Regional planning is also experiencing a revival as a result of the HUD program. By partnering with the DOT, HUD regional planning grants have made it possible to explore the true impacts of major transportation projects on local communities. In Central Iowa, a robust highway network makes it possible for anyone living in the 542-square-mile Greater Des Moines region to get anywhere by car in 20 minutes or less. While this is perceived as a key characteristic of quality of life in Greater Des Moines, the decades of planning focused on where the next major interchange will go has led to a declining urban population, diminished agricultural resources, and a development pattern that has significant impacts on flooding and water quality in the region. Central Iowa is about to change all that, having just adopted the Sasaki-led regional planning effort called The Tomorrow Plan, one of 42 HUD-funded regional planning efforts currently underway or recently completed across the country.

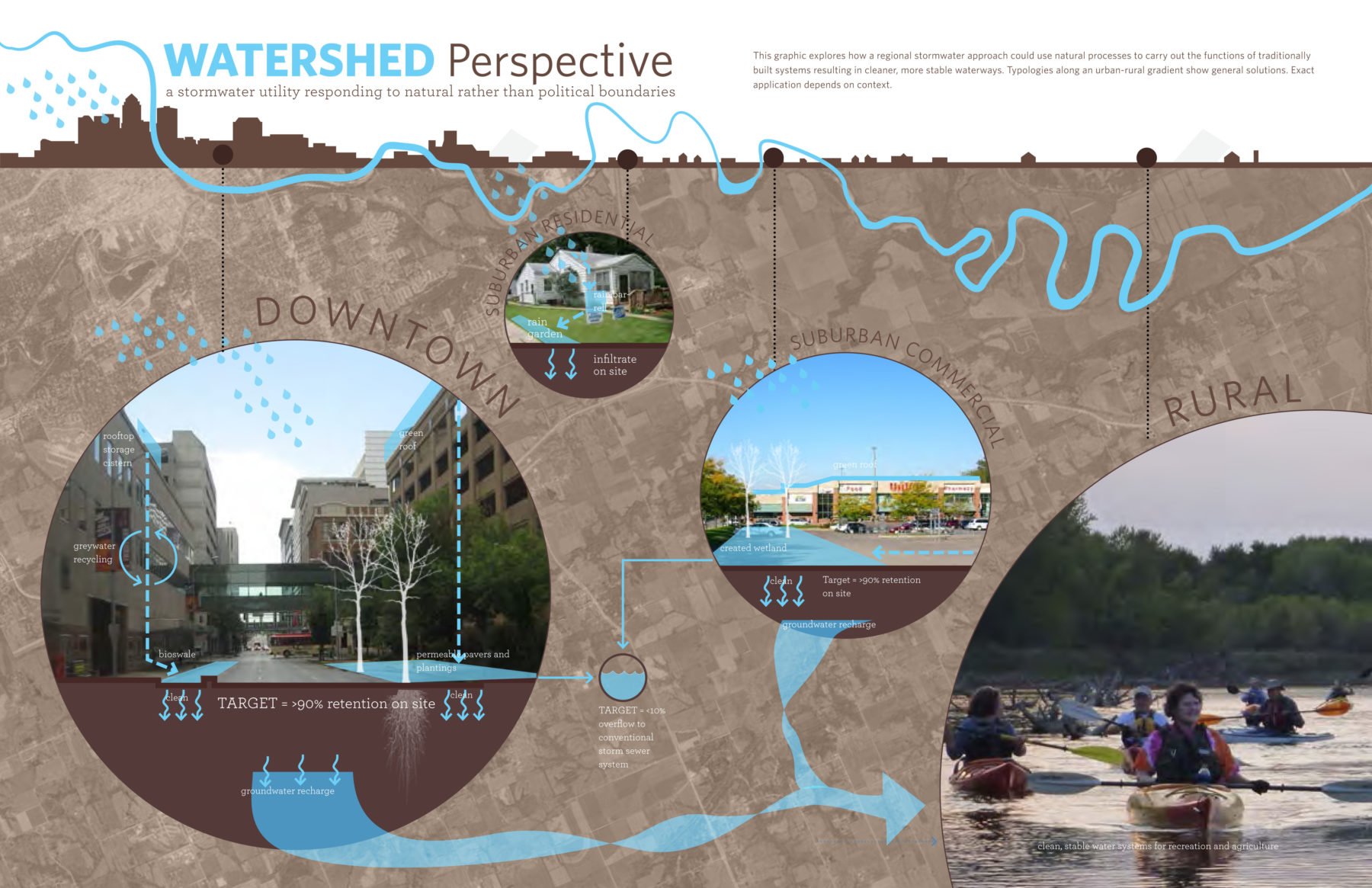

Click thumbnail for an explanation of how a regional stormwater approach could use natural processes to carry out the functions of traditionally built systems, resulting in cleaner, more stable watersheds

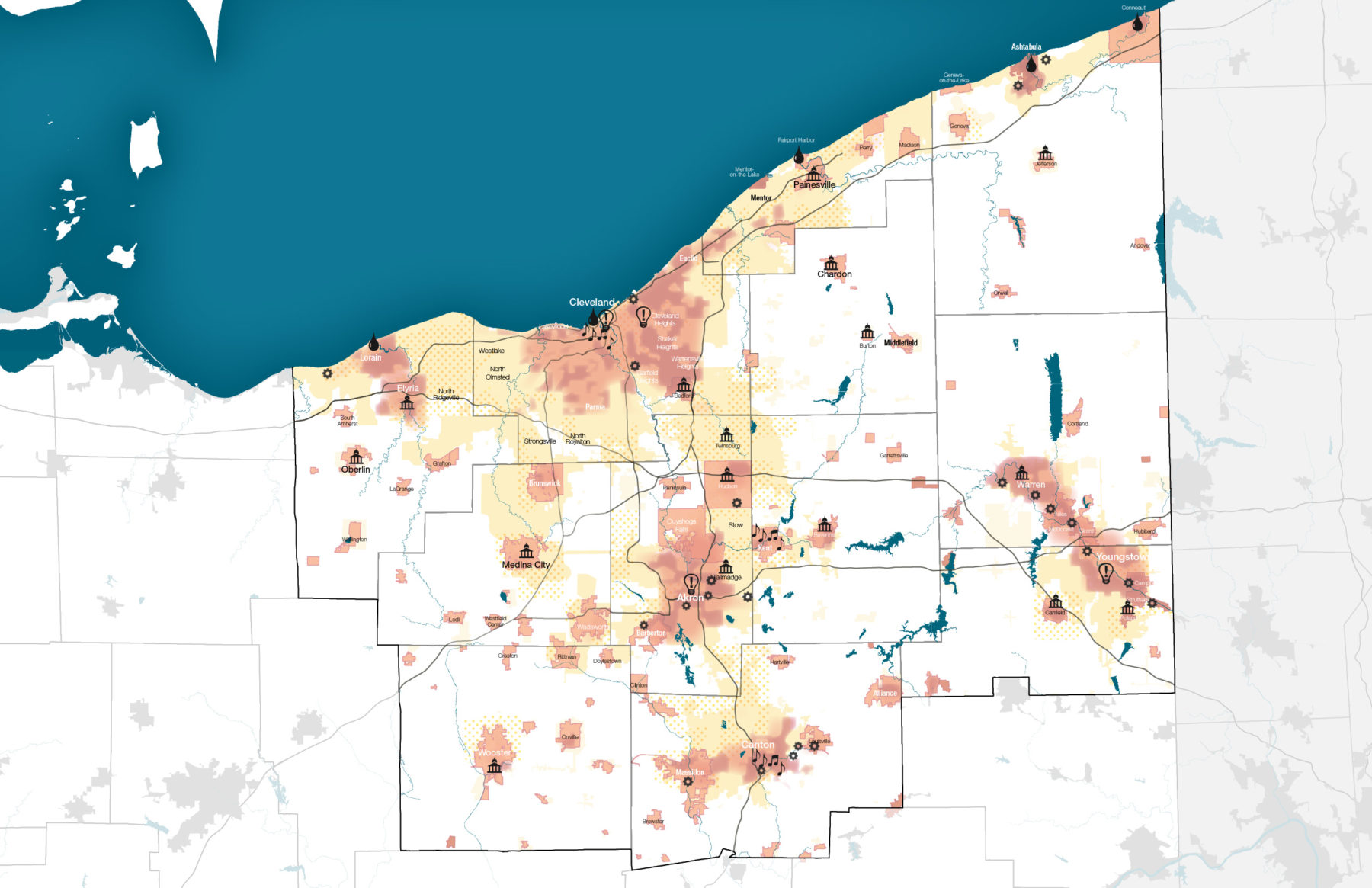

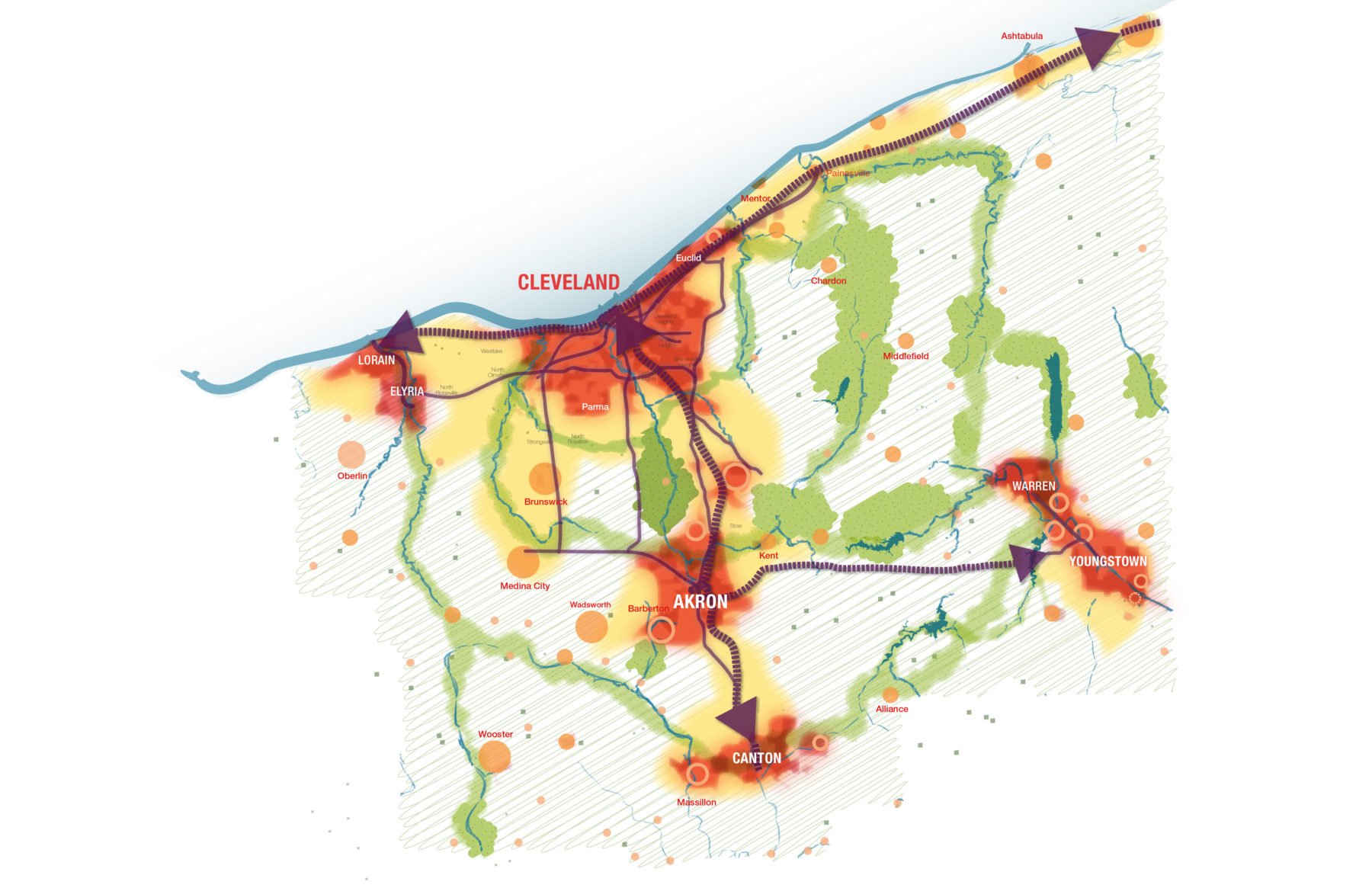

In Northeast Ohio, Sasaki has been leading another regional planning effort with a different set of challenges. As with many post-industrial legacy cities in the rust belt, population decline and “no-growth” sprawl have created a future that is not fiscally sustainable. The region is on a collision course with reality driven by three primary factors: 1) the increasing cost of building new infrastructure as people move into more rural areas; 2) the increasing cost of maintaining aging infrastructure in the urban areas that are being left behind; and 3) a decrease in the number of jobs and new commercial development, which continues to increase the residential tax burden in the region. To demonstrate the gravity of this situation, Sasaki developed a methodology for predicting the rate of abandonment across the region, painting a long-term future that has helped rally support for regional collaboration and policies that will improve the outlook for Northeast Ohio and serve as a model for other regions across the country dealing with similar issues.

Regional Vision for Northeast Ohio

This is the first in a series of articles that will begin to tell the story of Northeast Ohio through the lens of modern planning in America. It is a story that we believe has application beyond the rust belt—one that illustrates an important point in the history of planning where technology, engagement, and strategic thinking are coming together in new and exciting ways that will transform the profession. It is not enough for pockets of our nation to plan for the future. It must be a comprehensive effort that engages everyone—from the president to the pedestrians on Main Streets across America. We have built a heavy, expensive ship that is sailing in the wrong direction. Together, we can still right its course.