Embracing Disruption: Mohamed on Autonomous Vehicles

Sasaki

Sasaki

As AV (autonomous vehicle) technology rapidly improves, the reality of AVs taking to city streets is making its way into public consciousness. From Audi to Volvo, almost every major auto manufacturer has begun to invest significant resources in AV research. Many are developing in-house expertise through dedicated R&D groups, such as Audi’s Urban Future Initiative and Nissan-Renault’s Future Lab.

This article originally appeared in Autonomous Vehicle Technology as an op-ed by Sasaki urban planner Alykhan Mohamed.

While the technology is starting to take clear shape, the question of just how AVs will be integrated into our cities and lifestyles is less certain. Will autonomous cars contribute to an urban dystopia of endless commutes through sprawling cities, or a sustainable future where convenient and affordable mobility contributes to the vitality of our cities? The reality is likely to be somewhere in between, but it will take a collaborative approach between municipalities, urban planners, entrepreneurs, and engineers to harness the potential benefits of AVs.

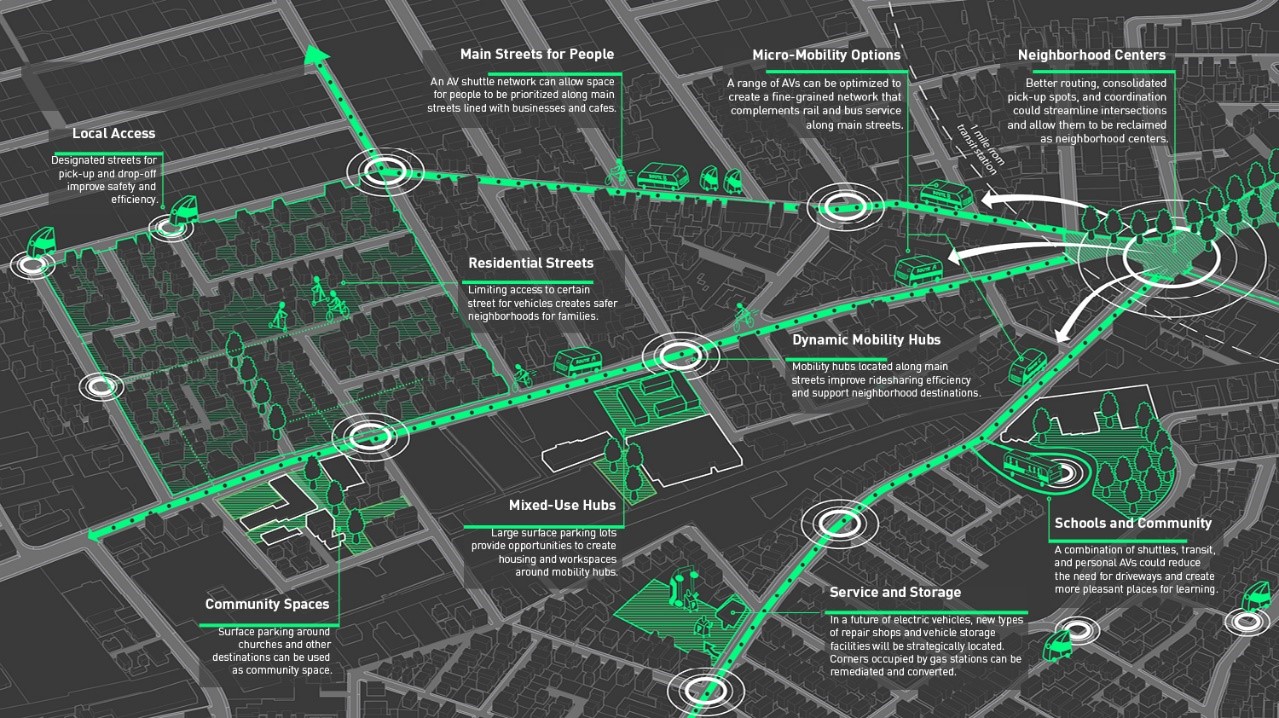

A network of mobility hubs and AV shuttles could be ideal for connecting urban neighborhoods

Urban planning grew from the need to organize the populations of large cities and a desire to provide a high quality of living. Today, the profession is grounded in a set of ethics that promote equity and sustainability. Most cities are eager to embrace innovation that clearly supports these core principles, but are reluctant to base long-term policy and investment decisions on an idea or technology that may look entirely different in just a few years. Looking back at the initial years of groundbreaking startups like Uber and AirBnB, the disruptive approach that these companies took may have enabled quick and early growth, but the lack of early engagement between cities and startups certainly left potential on the table. Many cities, such as Austin, TX, and Boston, MA, have hired chief innovation officers and are enthusiastic about partnering with innovators and disruptors.

In the short term, innovators may question the advantage of partnering with cities, rather than moving fast and breaking things. In the long term, however,

constructive public-private partnerships can lead to regulations that do more to support AVs than restrict them; integrated infrastructure that works with the vehicles rather than pose obstacles; and a smoother transition to SAE Level 5 autonomy.

So, what are the key conversations that entrepreneurs and engineers should have with urban planners? What are the issues that urban planners and city leaders are most excited and concerned about when it comes to autonomous vehicles? What are the big design and policy decisions that need to be thought through to realize the highest potential of AV technology and the places where we live?

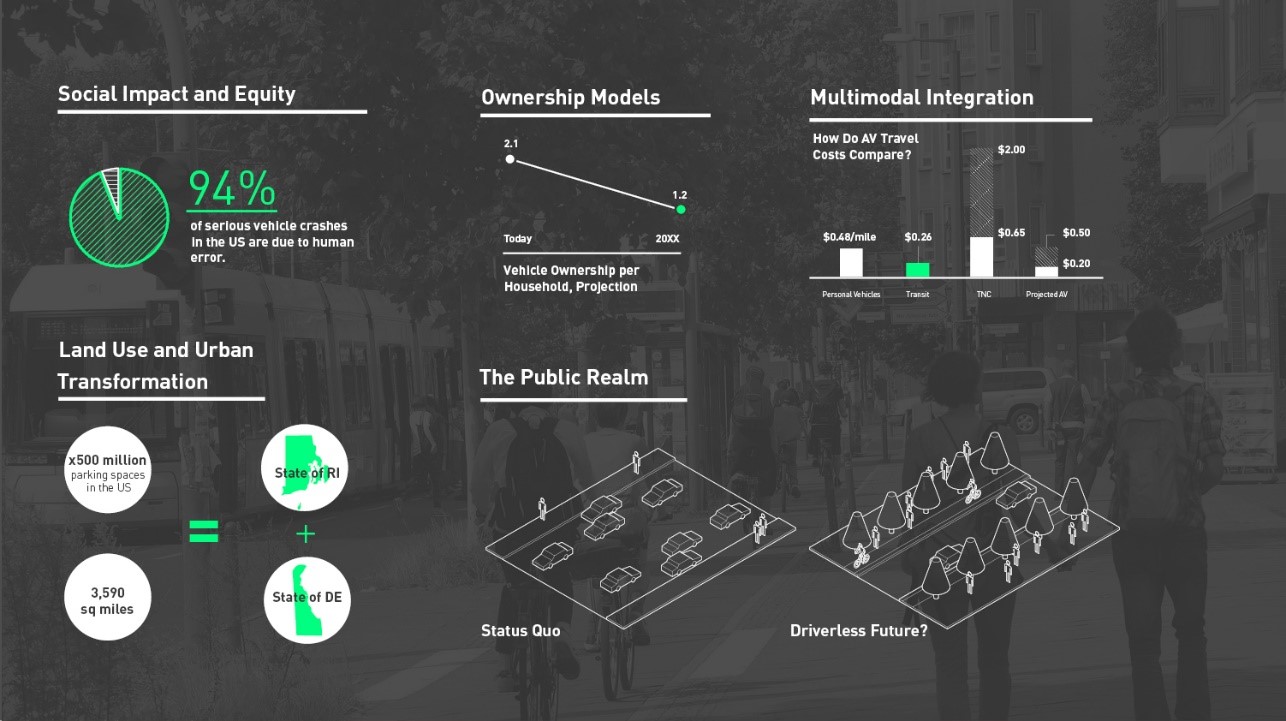

Creating a safe environment for pedestrians and cyclists is a growing priority at all levels of government. Cities across the country are embracing programs like Vision Zero and investing in roadway and intersection redesigns that calm traffic and create safer, more comfortable streetscapes. Almost 95% of serious automobile accidents in the U.S. are caused by human error. This fact alone has generated significant enthusiam for AVs and their potential to create safer streets. Mapping, sensors, and intelligent algorithms will, of course, play a key role in realizing the safety benefits of AVs. But what about the geometry of roadways, and the integration of intelligent infrastructure that facilitates communication between AVs, pedestrians, and cyclists? A new generation of roadways designed specifically for AVs could help realize the saftey goals of city leaders while faciliating a smoother transition to full automation.

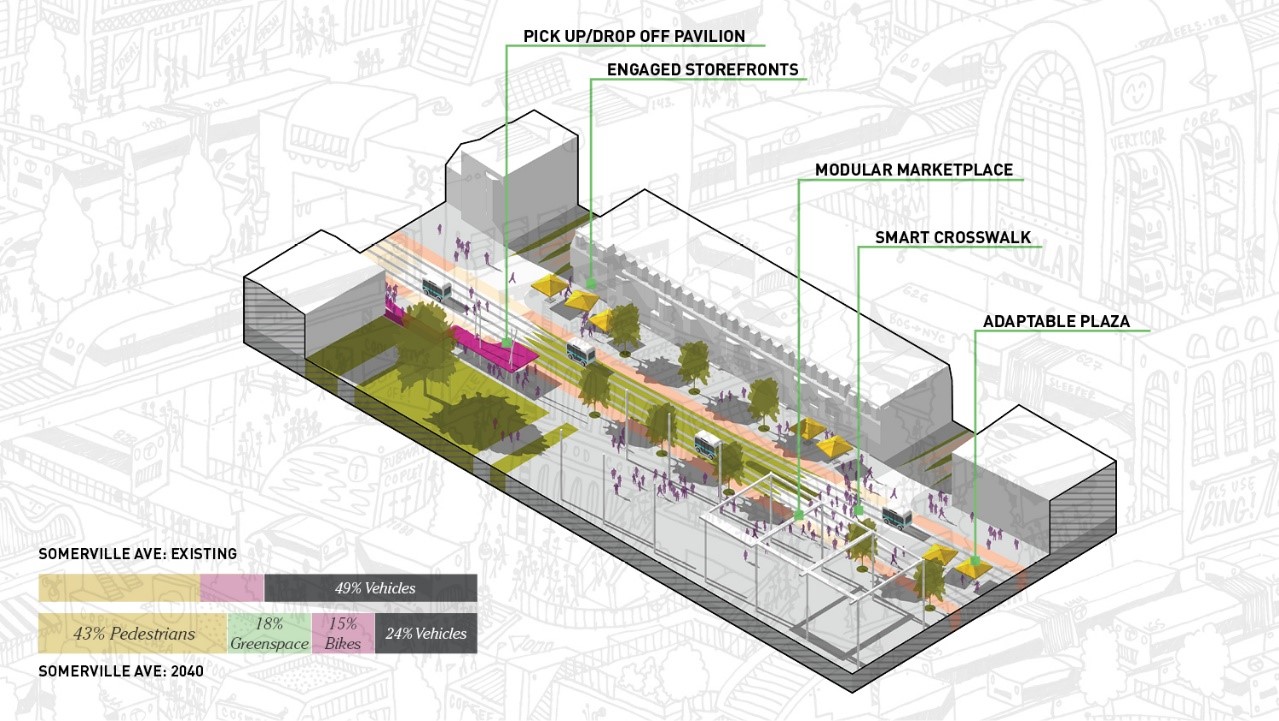

A main street typology where autonomous vehicles interact safely with pedestrians around mobility hubs, allowing roadway to blend into plazas and green spaces

Whether in Singapore or San Diego, there is a growing global aspiration to build “cities for all” by providing equitable access to jobs, housing, education, and transportation. Discussions about equity frequently revolve around ensuring access to transit for lowincome households, as well as older and younger residents who are unable to drive. While this strategy works well in the densest urban neighborhoods, most American cities lack the population density to support subways, light rail, or frequent bus service. As poverty in rural and suburban areas outpaces urban poverty, planners are seeking viable mobility solutions for these communities, like Houston’s on-demand transit program. By including low-income and elderly residents as part of a core target demographic, AV providers could expand their market while supporting the efforts of municipalities to provide equitable access to transit in the urban core.

In dense urban areas, mass transit will almost always be the most efficient and affordable means to connect people with destinations. As transit expert Jarret Waker states, this is simply a matter of geometry. Transit lines in these contexts are often the ones that break even financially, allowing cities to provide service to less central, lower density, and lower income areas that depend on public transit. The fear that AVs may undercut service on profitable downtown lines is one reason why many urban planners and city leaders are reluctant to embrace AVs. However, lower density areas that are less suited to mass transit are ripe for innovative and disruptive ideas. Many transit planners would be happy to embrace AV shuttle providers that might bridge “last mile” connections to commuter rail stops to increase overall ridership and allow underperforming bus lines to be replaced by affordable and equitable AV shuttle services.

Several metrics illustrate how Autonomous Vehicles could support the goals of urban planners and city leaders

Underperforming bus lines are often in neighborhoods that are urban enough that many residents might be happy to go car-free or perhaps give up their second car given a viable alternative. These are the neighborhoods where Uber and Lyft are often the most convenient ways to get around but remain too expensive as a daily commute option for individuals, and they have led to increasing traffic congestion—think East Austin or Outer Sunset in San Francisco. These neighborhoods might be ideal for the type of minibus service often seen in Asia and Latin America, but has not penciled out in Europe and North America because of high labor costs. With a strong consensus that shared-ridership and -ownership models are a natural fit for AV technology, AV shuttles could be an ideal addition to existing transit systems, helping to reduce car congestion in areas that are neither squarely downtown nor totally suburban.

A vision for how AVs could allow cities to transform car-spaces into people-spaces

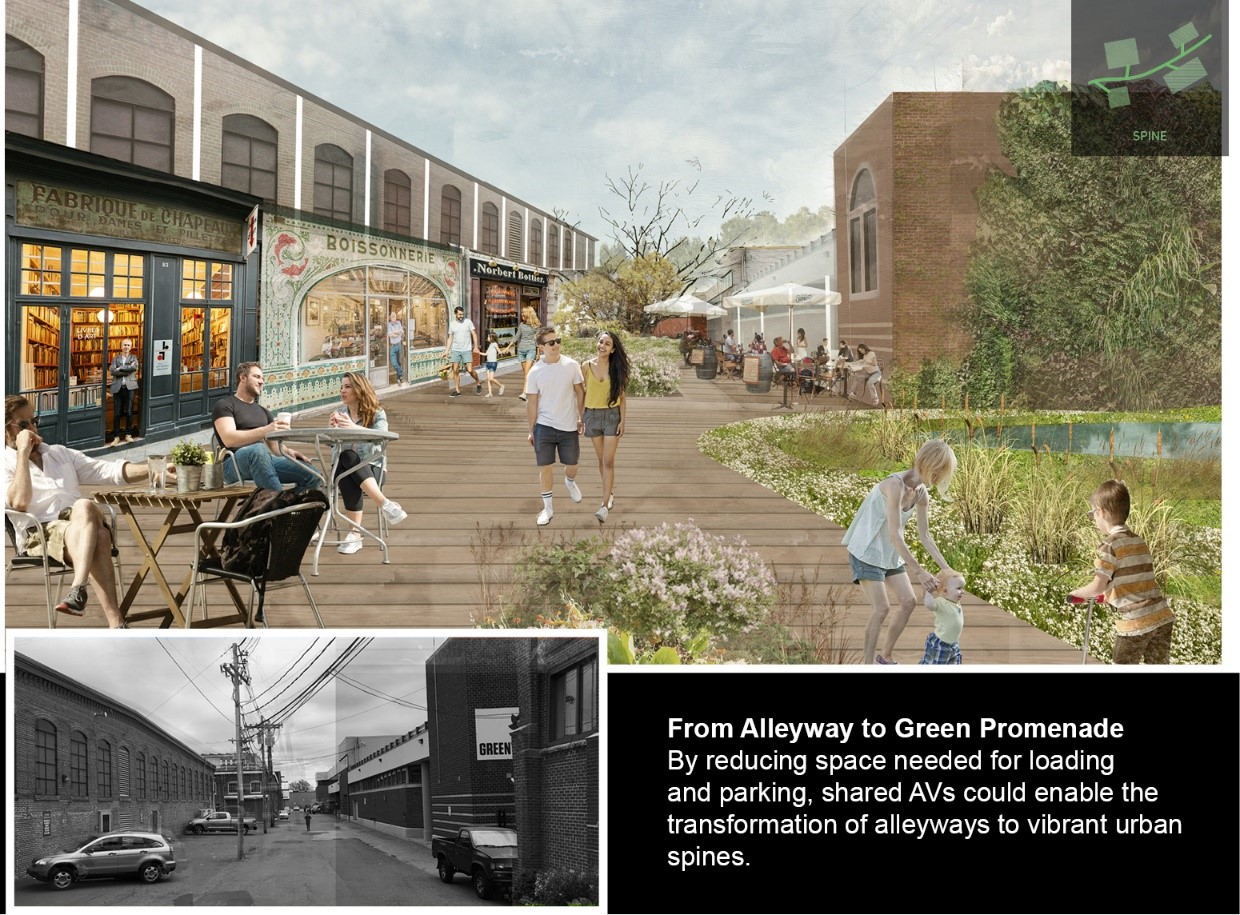

Commuting to downtown while living in a roomy suburban house with a backyard is definitely a lifestyle preference for many, but it is objectively inefficient from an environmental, fiscal, and transportation standpoint. Municipalities often struggle to break even when providing services to low-density suburban neighborhoods. The lower densities of these areas can’t support convenient mass transit, necessitating each family to own two or even three cars; this leads only to increased traffic and congestion, no matter how many lanes of highway are built. Almost half of the land area in most cities today is devoted to roadways and surface parking lots. If shared AV shuttles become widely adopted, the space we now use for driveways could instead be used for backyards and larger houses, allowing suburban comforts with urban convenience and efficiency. Rather than tentatively wait to find out whether AVs lead to a dystopia of sprawl and endless commutes, urban planners and AV researchers can proactively collaborate on more compact, sustainable, urbanism.

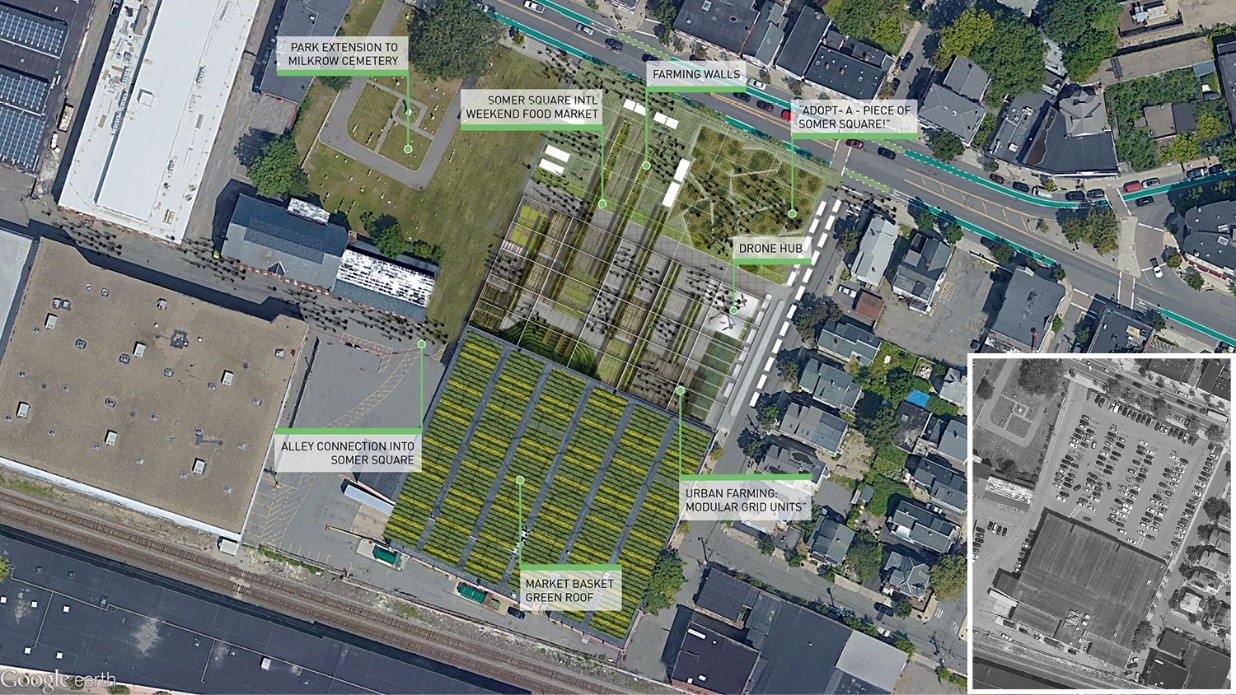

Integrated AV hubs could transform the vast parking lots of regional supermarkets into a variety of amenities, creating vibrant community anchors and helping these stores adapt to the uncertain future of retail

Perhaps what excites urban planners and designers the most about AVs is the potential to transform car spaces into people spaces, by reducing traffic, increasing safety, and encouraging more compact development. If door-to-door transportation were replaced with a network of carefully spaced designated pick-up and drop-off spots, we could see a more efficient overall transit network, activated neighborhoods, and healthy local business communities benefitting from increased foot traffic. The reduction in traffic would mean that, rather than designing every street around cars, cities could include wider sidewalks, green alleys, and pedestrian streets.

To sum it up, AV technology is quickly approaching maturity, with increasing investment in both hardware and software development. However, the success of AV adoption at scale depends as much on the ability of planners, designers, and policymakers at the federal, state, and city levels as getting the technology right.

Realizing the highest potential of AVs will require significant legislative changes and coordinated investment in infrastructure. The innovators and entrepreneurs developing AV technology are at a critical moment to capture unprecedented change, but their ability to seize the moment depends on engaging in conversations with these groups to define shared goals and build partnerships with cities from the outset of integration. It is these collaborations that will unlock the full potential of AVs to transform the future of mobility and lead to more vibrant, equitable, and sustainable cities.

For a deeper dive into Alykhan’s perspective, delve into his research here.