Modernist Icons: Rethinking Midcentury Architecture for the Future

Sasaki

Sasaki

Amidst the urgent environmental challenges of our time, the restoration of modernist structures emerges as a vital strategy for sustainable urban development. Sasaki is at the forefront of this movement in New England, leveraging decades of expertise to adapt and revitalize iconic buildings while preserving their historical significance and reducing their carbon footprint.

In a world where the construction industry accounts for 39% of the global carbon emissions, demolishing and building anew is not always the answer. If we want to build a more resilient and sustainable future, the best place to start is with our existing building stock. By restoring the modernist structures in our midst and adapting them to contemporary uses and environmental needs, we can help preserve their monumental character while significantly reducing their carbon footprint.

Sasaki combines decades of expertise in academic, civic, and cultural sectors with materially and environmentally sensitive approaches to renovating historic buildings for the 21st century and beyond.

Sasaki’s updates will preserve the monumental character of the LARTS Building while making changes to the building envelope that increase energy efficiency and improve comfort for its occupants.

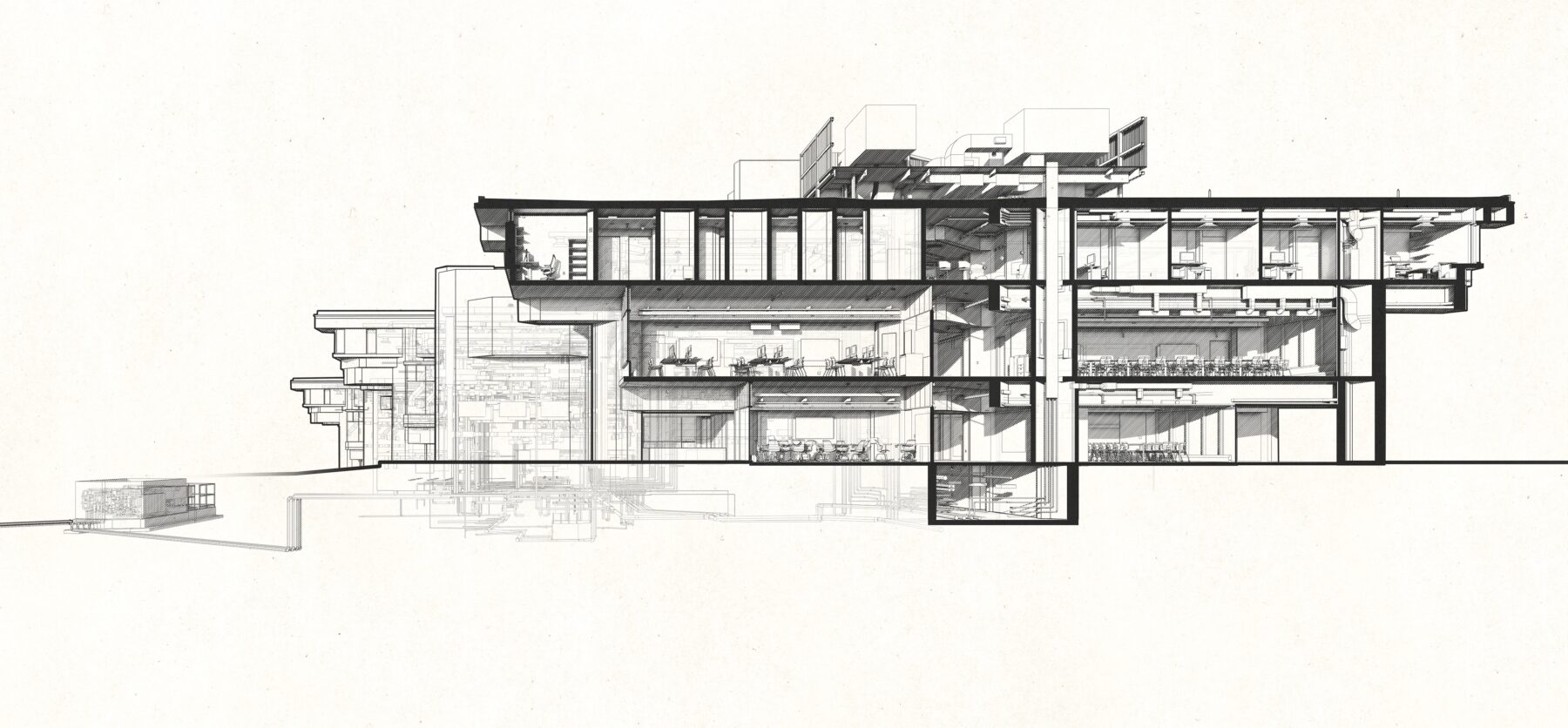

At the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth, we are undertaking a historic initiative to restore and reinvigorate the Liberal Arts and Sciences Building (LARTS), the centerpiece of Paul Rudolph’s visionary campus design initiated in the 1960s.

Rudolph emphasized the necessity of a central green space in his plan, from which a spiraling mall unfolds, creating dynamic movement and pathways along which to plot future buildings. The first structure completed under his purview, the LARTS building, functions as the spatial nexus of the campus as well as the social and academic hub of the community.

Despite its critical function and iconic presence on campus, the building urgently needs intervention. Its mechanical and envelope systems require modernization to meet contemporary standards of energy efficiency and accessibility. In collaboration with Finegold Alexander, Sasaki is tackling these challenges by replacing the roof and windows, implementing energy-efficient heating and cooling systems, and adding a new elevator—all while integrating our expertise in educational space planning.

Updates to MEP systems were made to work in harmony with the existing structure of Rudolph’s campus hub.

As we pursue clean energy goals, we are reimagining how learning spaces built in the 1960s can adapt to evolving curricula and new approaches to hybrid learning. This three-story building features a straightforward layout: the ground floor hosts all classrooms, the second floor mixes classrooms and offices, while the third floor is dedicated solely to offices. Ramps, stairs, and balconies snake across the north and south atriums, showcasing activity across floors and creating pockets for gathering, while cantilevered awnings infuse the exterior with heft and dynamism. This project will generally preserve the organization of the building while updating the spaces within to reflect current approaches to teaching and learning, student support, and student-faculty interaction. Our renovation aligns with initiatives to redesign some of Rudolph’s original classrooms, creating varied environments that accommodate flexible class sizes and diverse uses.

Some renovations involve transforming the program of the building altogether. Since its founding in 1958, the Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra (BYSO) has lacked a dedicated home base. Renting from various spaces across the city has inhibited the organization from fostering the sense of community that comes with a fixed hub for operations and gathering.

Sasaki helped the youth nonprofit find a new, permanent home in a former Sunday school building designed by I.M Pei & Partners as part of the Christian Science Plaza in downtown Boston. Our history with the site goes back to its architectural origins–Sasaki collaborated with Araldo Cossuta and I.M. Pei & Partners in the 1970s to design the 9-acre open space in the heart of Back Bay, which features an iconic 690-feet long reflecting pool that extends across the length of the plaza.

The exteriors remained consistent with I.M. Pei’s original design, with graphic treatments that indicate the BYSO’s presence.

A location downtown was key for the organization, as many of the students rely on public transportation to commute to rehearsals. While the site fulfilled this geographic requirement and brought the BYSO in close proximity to the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the building’s landmarked status and its existing program posed a different set of constraints.

In balancing the BYSO community’s unique needs with the historical and structural demands of the building, Sasaki implemented a number of creative and minimally invasive interventions to transform the former Sunday school into a space conducive to musical performance, teaching, and gathering. Though the quadrant-shaped structure posed acoustical challenges, Sasaki worked within these programmatic limitations to create varied spaces for individual, group, and orchestral rehearsals.

In the main orchestral space, updated hardwood floors and acoustical clouds enhance sound quality within the concrete walls, while ten sonically isolated practice rooms on the second floor have been designed to look out onto the plaza, enlivening and brightening spaces often known to be cramped and windowless. Newly created mid-sized rooms on the third floor accommodate chamber groups and lessons, allowing different forms of rehearsal to occur simultaneously across the building.

As all changes to the exterior of the building needed to be approved by both the church and the city, Sasaki worked to retain the exterior as true to Pei’s original design as possible, and focused on the interiors as the site for expressing the BYSO’s playful and vibrant identity. A bold red carpet runs across the ramps and corridors, infusing a pop of color into the otherwise staid concrete interiors. The addition of an elevator addressed much-needed accessibility requirements, and newly built furniture and meeting areas encourage relaxation and socialization. By blending together the urban legacy of the building with the youth orchestra’s culture of inclusiveness and fostering creative growth, the BYSO’s new home offers an imaginative, mission-driven model of adaptive reuse.

Red carpets brighten the ramps that connect the three floors of the building.

Buildings are not the only place where ecologically and historically mindful adaptations can take place.

For decades, Boston City Hall Plaza played host to large-scale civic engagement, with gatherings, protests, and celebrations unfolding beneath the towering presence of the city’s iconic Brutalist City Hall Building. Locals found the brick expanse wind-slept and desolate, with many describing it as a “red tundra”. The slopes and terraced steps created barriers to accessibility, while the emptiness of the space led to a noticeable lack of shade and amenities.

While designed to evoke the monumental character of European piazzas, the sweeping space often overwhelmed the public, making it difficult to relate to at a human scale.

Sasaki’s transformation of the plaza entwined community and environmental changes to create a healthier and more vibrant civic space for residents and visitors alike. The addition of over 250 new trees, 3,000 shrubs, and 10,000 perennials and grasses has brought shade to over 50% of the 5-acre site while minimizing heat-island effects. An array of new seating options sited throughout the plaza further encourages people to sit, relax, and gather.

“Hanover Walk,” the project’s central promenade, is a universally-accessible circulation route that spans across the site and connects people to the North Entry of City Hall – now renovated and open for the first time since September 11, 2001.

By mitigating the site’s 26-foot elevation difference with a new sloped promenade, the new plaza creates equitable access to as many locations and building entrances as possible. A colorful, geometrically eclectic playscape pays homage to the forms found in the modernist architecture while toying with their rigidity and regularity. Updated porous paving materials and plant beds are key components in a new water management system, which absorbs rainwater to replenish groundwater, irrigate the plants throughout the plaza, and connect to the city’s stormwater system.

The subway tunnels running below the plaza were carefully unearthed and reinforced in order to transform the stepped terrain into a series of smooth gradations.

The playscape embodies a “kinder brutalism,” recasting the materials and geometries of modernist architecture as opportunities for creative play.

This focus on crafting more usable and welcoming spaces extended to the interior as well. The North Entry, which served as the primary entrance in the original building scheme, had been closed since September 11, 2001. Through expanding the vestibule and adding custom light fixtures, we renovated and reopened the entry to create a more light-filled, welcoming access point that restores connections between the city and its public.

A new civic pavilion offers space for multi-use programming as well as accessible restrooms.

The North Entry, closed since September 11, 2001, underwent renovations that resulted in an expanded vestibule, new custom light fixtures, and a modern security screening station, streamlining access for visitors seeking city services.

Mid-century architecture represents a unique era, embodying the aspirations and values of its time. However, dismissing these buildings as outdated relics prevents us from recognizing the significant social and environmental benefits that adaptive reuse can offer. By implementing historically mindful and structurally sensitive interventions, we can breathe new life into modernist icons, enhancing their functionality and relevance. These thoughtful restorations create lasting improvements in the health and vibrancy of the communities that engage with these spaces, allowing them to thrive in today’s world while honoring their history and past.

For more information contact Fiske Crowell or Carla Ceruzzi.