Evolving the Role of Community in Planning

Sasaki

Sasaki

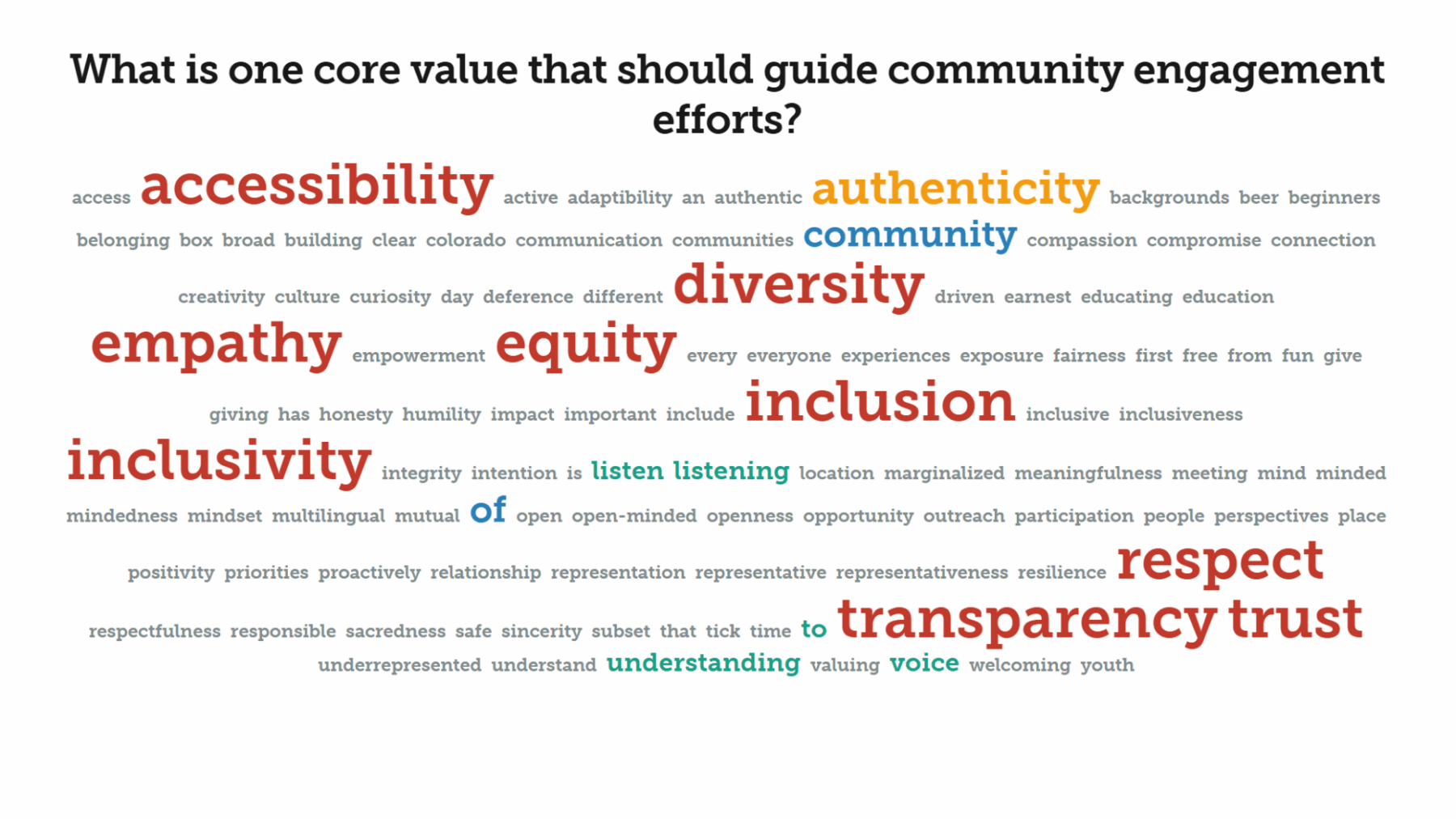

At this year’s National Planning Conference in April, we asked a room of planners “What is one core value that should guide community engagement efforts?” The responses revealed that engagement is not a technical exercise, but a fundamentally human one. Common shared values included accessibility, inclusivity, authenticity, empathy, transparency, and trust. These are all values that we aim to uphold in our practice of community engagement at Sasaki, as we actively seek ways to foster stronger relationships with the communities we work with, create a shared sense of ownership, and build trust within the planning process.

As the nature of planning becomes more community-driven, planners are recognizing the need for more inclusive, equitable, and empowering engagement strategies. Our conference session, “Reimagining Public Participation for more Inclusive Planning Processes” aimed to explore those strategies through an interactive discussion that challenged participants to consider how they would reimagine the community engagement process.

Responses to the poll question posed to audience members.

The session was structured as “fishbowl discussion,” seeking to foster dialogue and break down the usual presenter-audience dynamic. The fishbowl discussion has an inner and outer circle—while the inner circle discusses a topic, the outer circle practices active listening. Participants can move from one circle to another as they choose. In its ideal form, this technique allows for a genuine exchange of ideas, where participants can build on each other’s insights and challenge each other’s assumptions.

The session brought together a diverse range of voices within the planning and design field, including public sector planners, community activists, students, and private-sector professionals. Through a lively discussion, participants surfaced shared perspectives, differing viewpoints, and innovative ideas, offering valuable lessons for strengthening and evolving our approach to community engagement today.

“Contribution is the only value…for it brings the advantage of giving more than one person’s slant to a problem, and shows how differences may be harmonized by active discussion.”

Hideo Sasaki, 1957

The conversation was framed around the IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation, a guiding tool to help organizations determine and implement the appropriate level of public involvement in decision-making processes. The IAP2 Spectrum organizes the level of public participation within a community process on a range from ‘inform’, where the public is merely provided information, to ‘empower’, where the final decision making power is placed in the hands of the public.

Despite the diversity of professional backgrounds in the room, many agreed that collaboration is a valuable and attainable goal across a wide range of planning contexts and project types. There was a shared recognition that bringing the community along on each step of the planning process and incorporating their feedback and recommendations into decisions to the maximum extent possible leads to better outcomes.

At Sasaki, we strive to create planning processes where the community is an essential partner with valued expertise and opinions, and a critical role in ensuring the success of the project. Reflecting on our practice, we thought back to experiences where collaboration with the community led us to better design and planning outcomes.

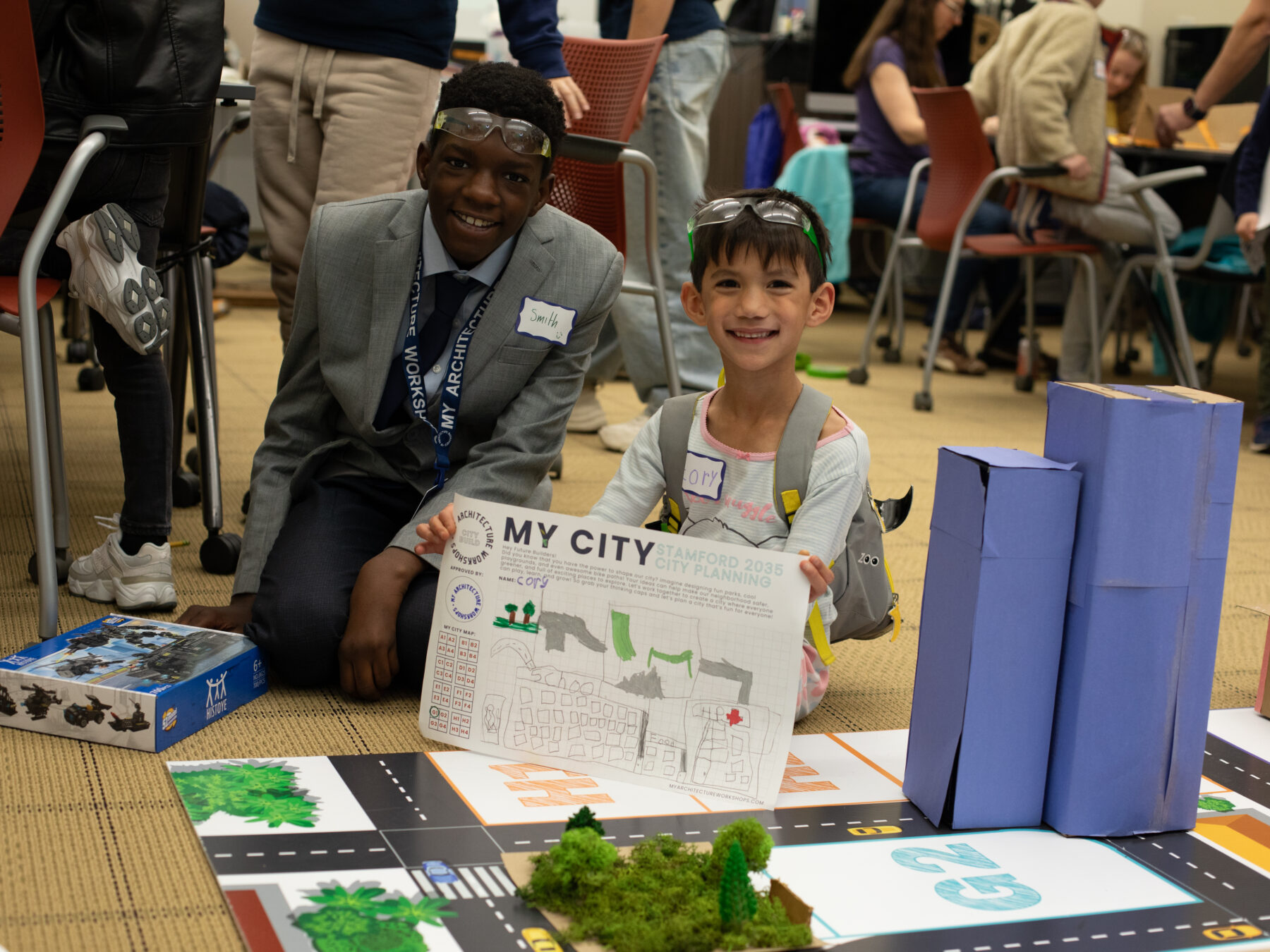

A particularly intricate dance of collaboration has been the work of weaving in diverse voices, especially those of young people. Inspiring kids to care about their city has been a powerful force, reshaping how comprehensive planning unfolds in urban environments.

My Architecture Workshops, Sasaki’s local consultant for the Stamford Comprehensive Plan 2035, championed youth engagement, giving children a voice in shaping their future city. Photo courtesy of My Architecture Workshops.

Our civic engagements bring us into contact with multiple neighborhoods, often marked by different histories of disinvestment. We are consistently moved by residents’ deep commitment to place and the ways in which they hold their local organizations accountable. Our contribution is to inspire creativity and provide the necessary tools for people to be able to create change in their own communities. By building effective platforms that ask insightful questions, we can encourage productive discussions that push the boundaries of what’s possible.

To inform the Great River Greenways Technology Masterplan, Sasaki conducted workshops throughout the neighborhoods the greenway traversed, revealing a wide spectrum of public needs regarding technology in public spaces.

Adapting engagement approaches to the needs of the specific communities we work with is essential to build trust, ensure accessibility, and empower participation. When working with historically marginalized populations such as immigrant communities, this requires overcoming past distrust and language barriers through multilingual outreach, culturally competent strategies, and partnerships with trusted community leaders.

As part of the Phillips Square design process, Sasaki hosted a charette held in multiple languages – Cantonese, Mandarin, Toisanese, and English – that invited community members to actively participate in shaping the final design of the plaza.

Empowerment—the final level on the IAP2 Spectrum, which involves placing final decision-making power in the hands of the public—is an outcome less often achieved in reality. As session participants debated the notion of empowering the public, it brought up many considerations within the nuanced challenge of finding the right balance between professional expertise and community ownership. Some participants noted that empowerment is not always the intended or necessary outcome of every participatory process, depending on a specific project’s goals and needs. Others emphasized the importance of building knowledge and capacity within the community first, enabling members to make well-informed decisions and fully understand the benefits and tradeoffs involved. The topic of compensation also arose, with many agreeing that if community members are to take on a greater role in the planning process, their time and contributions should be fairly compensated.

As the discussion shifted to the final prompt that asked participants how they would envision reinventing the planning and engagement process, one person suggested incorporating planning into the school curriculum, arguing that a more civically engaged citizenry begins with education. Another proposed making participation in planning processes a civic duty, akin to jury duty, to ensure broader representation and commitment. A third, inspired by the power of storytelling, advocated for using theater and performance art to make planning issues more accessible and engaging. These ideas, while perhaps unconventional, sparked a lively debate. They challenged us to think outside the box and to consider how we might transform public engagement from a procedural requirement into a truly transformative experience.

The journey towards participatory planning requires time, effort, patience, perseverance, and a commitment to putting the community first. Yet, if we are willing to embrace new approaches, to learn from our mistakes, and to keep the conversation going, we believe that it’s possible to build a future where planning truly reflects the needs and aspirations of all members of the community. The conversations in this session showed us that this vision is achievable, reaffirming our belief that inclusive, community-driven planning is not only necessary, but entirely within reach.