Designer Spotlight: Surbhi Agrawal Explores How Planning and Data Shape Digital Equity

Sasaki

Sasaki

Digital equity defines how communities change and grow over time.

While data-science is not new to planning and urban design, it has increasingly become a way to shape more accessible and equitable plans. For Sasaki Data Analyst & Planner Surbhi Agrawal, it is the intersection of technology, data, and planning that gives way to more impactful design. Today, Surbhi continues to build on her passion for creating connections as an urban technologist looking to the future of access and what it means to empower cities today.

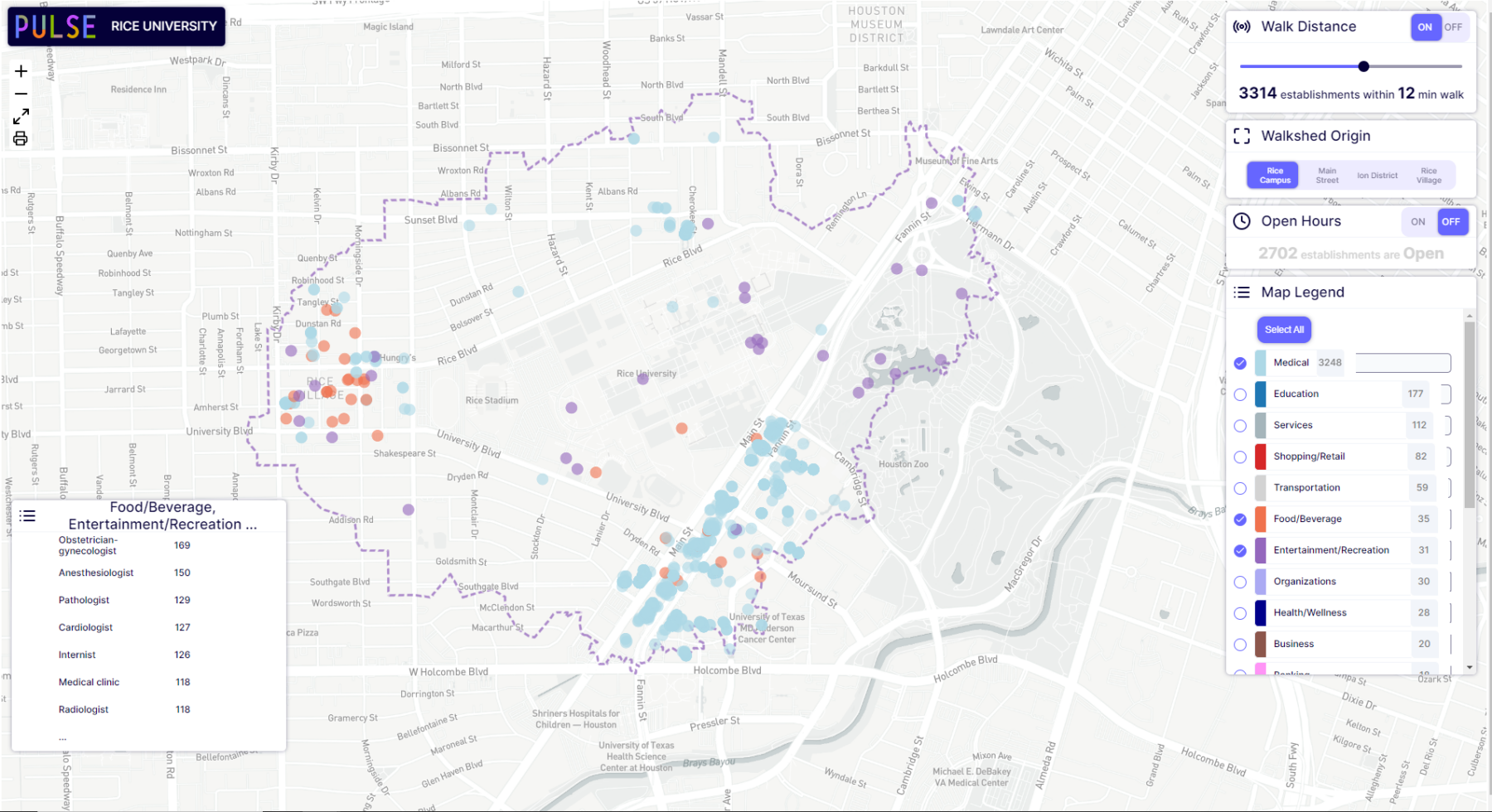

I think of myself as an urban technologist and data scientist, as well as an urban planner. Those are the main hats I wear. My work often involves UI and UX design and GIS mapping, but at its core, it revolves around applying thoughtful technology and data analytics to urban development.

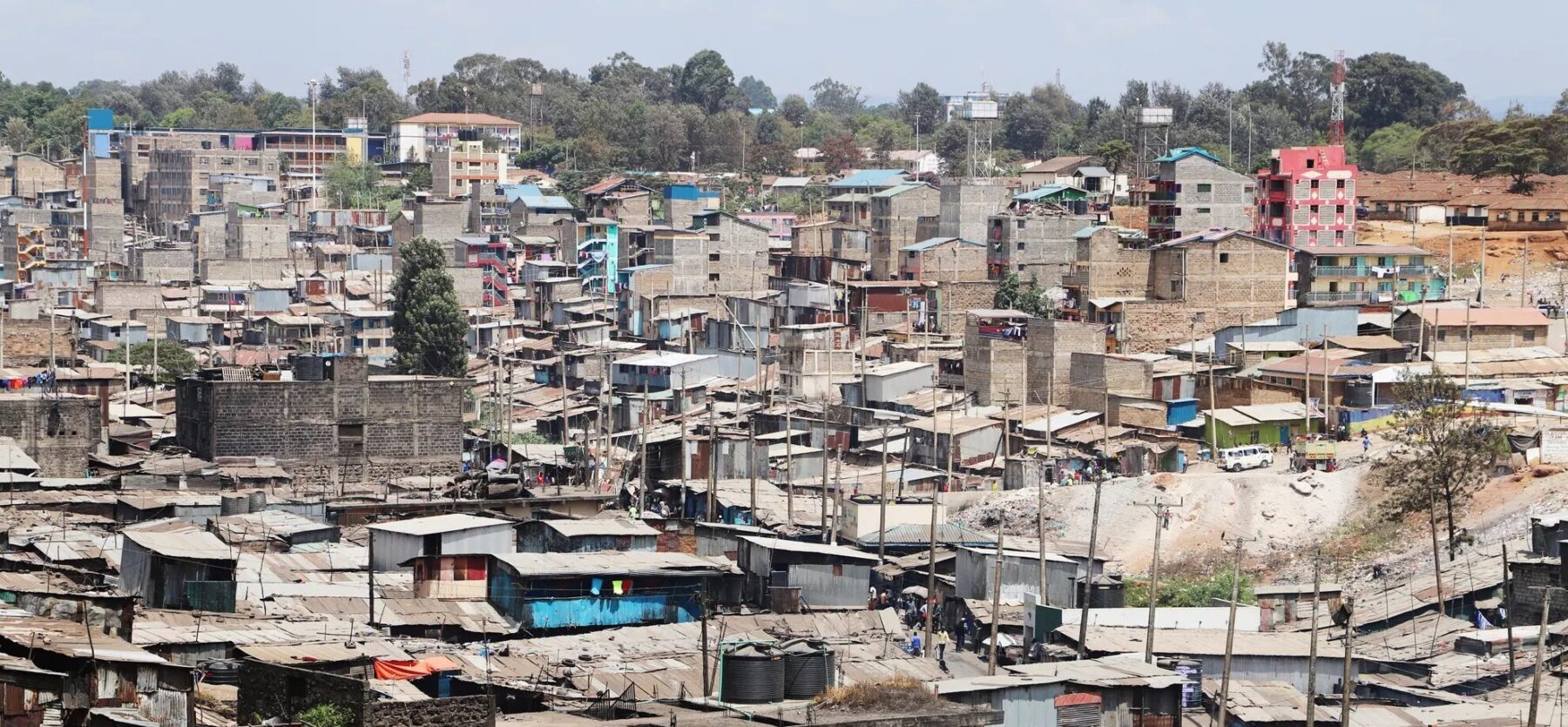

Surbhi’s work on Living Data Hubs aimed to address the critical infrastructure and data gaps found in informal urban communities in Nairobi, Kenya.

At Sasaki, Surbhi has been using data science methods to develop innovative methods to study the context of Urban Design projects.

Even though I studied architecture, I was always interested in the larger context of how architecture operated in the city. Then when I went through urban design school, I realized I was more interested in the even larger ecosystems of that. So that’s what landed me in planning: questions of policy, socioeconomic pushes and pulls, trying to understand design as a piece of the puzzle, then how it is all connected. That was the shift.

It was a time when the emergence and uptake of technology products like Google Maps Uber were changing the urban navigation experience globally. I was traveling a lot through different cities and strongly felt that while this was a push that was coming from technology. Urbanists and city governments weren’t equipping themselves to handle these questions, so I wanted to bridge those worlds.

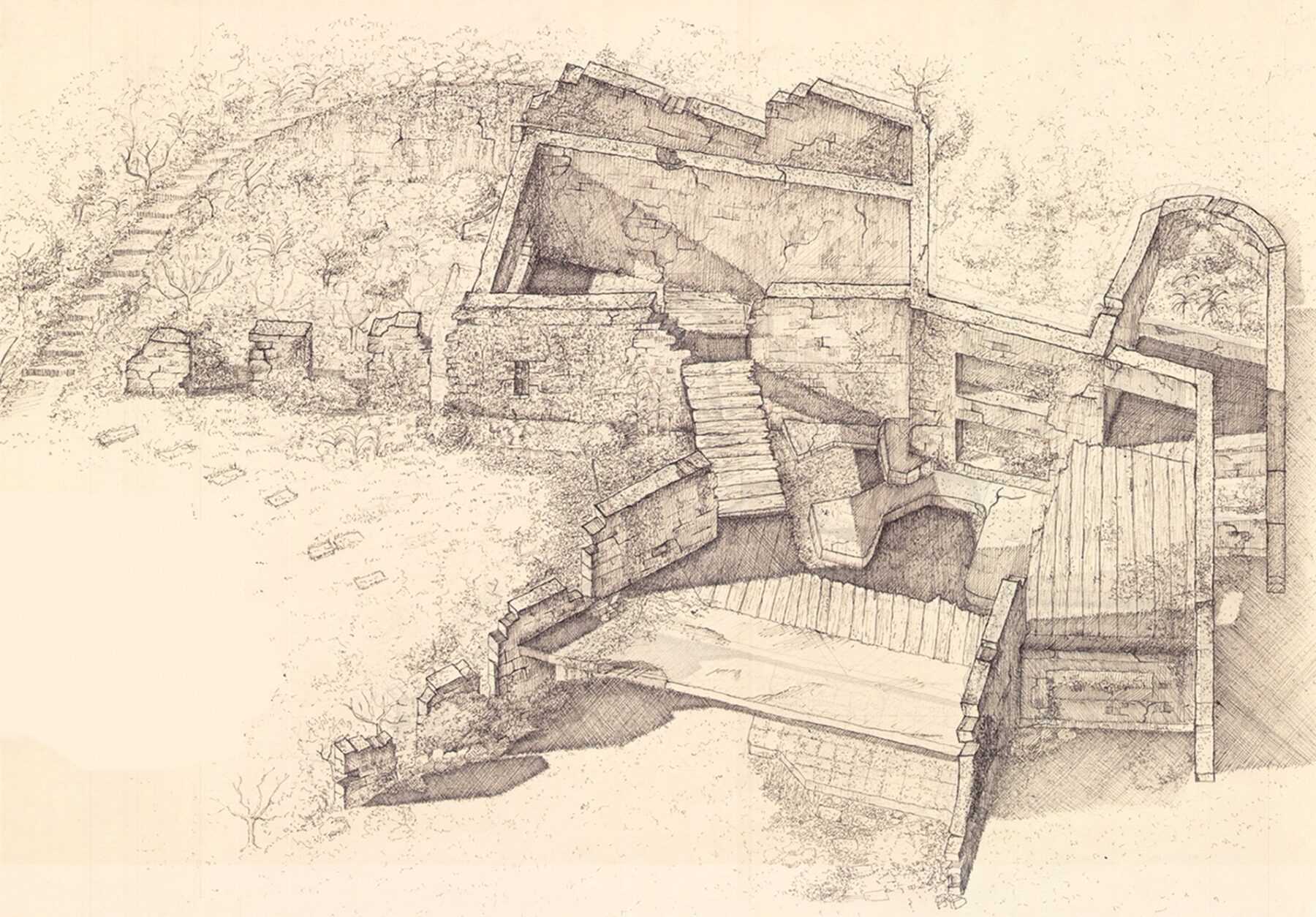

I grew up in India and there’s a rich culture of built heritage there. I think that was always in the back of my mind, and then also at a very fundamental level in school. I was always interested in both science and creative pursuits. I found architecture to be just the right mix of thinking about creativity, but in a very pragmatic and practical way. Everything has to function eventually. So that’s where the entry point to architecture happened.

Surbhi’s study and documentation of Nilai Lake House in Maharashtra, India.

"On its own, you can manipulate data to say whatever you want. But it becomes meaningful when you combine data with stories, lived experiences, and people."

It’s humbling and exciting to help Sasaki set up its urban technology practice. We’re exploring how cities can use technology to enhance urban planning and decision-making. For instance, we recently won a project to design the urban technology plan for the St. Louis Greenway and it’s really open-ended. We are helping the city figure out what answers they can get using technology. Can they get information about utilization of the Greenway, environmental factors, advance digital equity, can they implement wireless infrastructure on the Greenway so they have access to the internet for visitors, those kinds of questions. It’s exciting to explore this field of work as we set up this practice with many projects underway.

My work is diverse, ranging from advancing digital equity in housing projects in New York to analyzing geospatial data for flood preparedness. I get to look at large data sets or even small data sets for different projects and help teams make sense of additional information that traditionally you wouldn’t use. For instance, we are working with the Denver Parks department to help them develop a scoring method to evaluate the design quality and asset conditions of parks across the city to support their capital planning efforts.

Sasaki is quite good at understanding information from data and quickly making design decisions. There are a lot of very interesting pilot projects, and it’s wonderful to be a part of that.

Surbhi curated an exhibition on sensors used in Amsterdam under the Responsible Sensing Lab at AMS Institute.

I think data is always only a part of the story. Which is why I think it’s interesting to be in a planning practice, not an entirely technology practice, to answer these questions. Because the thing with data is you can manipulate it and wrangle it to say whatever you might want to say. It becomes really meaningful and interesting when you start combining data with ongoing stories, lived experiences, and people. I believe in engagement on both ends of the spectrum. You can host an online survey, but then you also go and talk to people, talk to all of the stakeholders, and then when you combine the two things, you start seeing meaningful information.

The data might say a certain demographic feels a certain way about a place, but then when you go and talk to that set of people is when you will understand exactly what makes that place meaningful. Numbers only really mean something when combined with people’s voices. We work with both those quantitative and qualitative understandings.

"At the heart of my work is digital equity, ensuring that technology upholds democratic values and serves the community effectively."

One thing I came to understand and appreciate is that there’s a lot of context to urban technology projects: work around responsible design, transparency, data minimization, and digital equity rights. How do you establish trust in public space around digital technology? At the heart of my work is digital equity and how it shapes urban planning and technology deployment, ensuring that technology upholds democratic values and serves the community effectively.

There are a lot of questions to this work: how do you understand and communicate about technology? How do you challenge how things currently work? How do you access data? True transparency is when citizens have access to data, when they can advocate for their rights,and when they have a say in what they want their city to be.

Kibera’s informal settlements.

Surbhi working in Nairobi.

Certainly, our work is very ecosystem driven. We need to talk to all the stakeholders to understand their needs. Then you need to have a very clear understanding of what the community wants to make sure it’s the right thing to do for the community. Whether we’re implementing new technologies or designs, it’s crucial that all stakeholders are involved and benefit from the process.

For instance, one of the new projects we’re starting is a resiliency planning toolkit. This is about disaster resiliency, but also introducing new tools to engage with diverse stakeholders. We’re working with Miami Valley Regional Planning Commission to support their current resiliency efforts. That includes establishing a toolkit to support community resiliency decision-making related to the region’s experience from the 2019 Memorial Day tornadoes.

As part of this toolkit, we are helping them map the most vulnerable populations, to think about mitigation strategies both for stakeholders and for the communities, and use a digital platform to increase outreach in a way that’s accessible. We are directly helping the community and anyone who might not understand all the technicalities. For instance, many of the most highly vulnerable populations in the region are remote rural communities. We need to communicate complex information in a way that makes it comprehensible for all the different stakeholders., Using digital media and data tools, we are able to provide solutions to a very traditional planning problem.

As a part of her Digital Equity Work in India, Surbhi engaged with NGOs, children and teachers in a digital literacy center in an informal settlement in Delhi.

Across everything I’ve spoken about urban technology, I’m deeply interested in the question of digital equity. How can we create equitable access to digital technologies and information? I think that really is a starting point to any of these topics and ideas about digital rights.

Across the nation, states are starting to draft digital equity plans. All the major cities are beginning to create, or already have, a digital equity plan. New York has one, Philadelphia has one, Boston has a digital equity officer as well. If underserved communities don’t have meaningful access, then we are only answering urban questions for privileged populations. I’m interested in how we use urban technology and planning for socioeconomic development opportunities and how we increase access for everyone. For me, the central question is digital equity.