Enabling Synergies: Integrating Ecology with Landscape Architecture in Design Practice

How do Sasaki’s ecologists use their blend of landscape architecture and ecology schooling and expertise to influence design decision-making?

Sasaki

Sasaki

As climate change increasingly impacts communities, landscape architects are envisioning and implementing places that are adaptive and resilient in current conditions and anticipated extremes. To convey climate-related challenges and solutions in the built environment, a dry list of figures won’t suffice: designers must be effective visual communicators. Landscape architects employ creative graphical techniques to explain complex information and propose ideas.

A new book, Representing Landscapes: Visualizing Climate Action, edited by Nadia Amoroso, illustrates ways that landscape architects visually present climate adaptation and resilience concepts. The chapter by Allyson Mendenhall, “Communicating Landscapes of Complexity with Chunks and Comics,” presents two visual techniques—the chunk and the comic—employed by Sasaki’s landscape architects across a wide range of projects.

Read on for an excerpt of the chapter.

It’s a long-held belief among designers that they must draw to think. Designers embark on drawing forays to discover alternatives and make incremental decisions to advance a design. At Sasaki, the multidisciplinary design firm founded by Hideo Sasaki in 1953, we develop graphics to elucidate an idea or draw attention to a conflict that must be resolved. As designers, we serve as distillers and translators of complexity. We put ourselves in the shoes of the people evaluating a design proposal and determining its viability–whether subject matter experts or community members with deep knowledge of the places they live and work. We use many methods to depict adaptive and resilient landscapes in response to climate change, including Chunks and Comics, for which explanations and examples are provided below.

Many of Sasaki’s projects have a significant below-ground engineering component or jurisdictional knottiness that adds complexity to the design process and solution. To understand the intricacies of a site and to explain them in a way decision-makers and the public can understand, designers must unpack the systems and pieces of the landscape and determine how to represent them with graphic clarity. One device for depicting complex landscapes that is well represented in Sasaki’s work is the use of small axonometric sections, which staff refer to as landscape “chunks.” These little diagrams serve as abstract vignettes to depict—with added dimension suggesting surface and below-ground layers—existing conditions or proposed systems on a site. Landscape chunks help the design team to break past “the two dimensionality of the endless flatlands of paper and video screen,”v which Edward R. Tufte believes is an “essential task of envisioning information.”vi This kit-of-parts approach is effective in examining a single component to sharpen understanding of the challenges and possibilities of a landscape’s systems.

Uniform in shape and size, and often arrayed in a series for easy comparison, chunks are effective to show a sweep of landscape conditions and design options. Akin to the “small multiples” approach advocated by Tufte in Envisioning Information, landscape chunks are “information slices [that] are positioned within the eyespan, so that viewers make comparisons at a glance–uninterrupted visual reasoning. Constancy of design puts the emphasis on changes in data, not changes in data frames.”vii Summarized by Tufte, “small multiples reveal, all at once, a scope of alternatives, a range of options.”viii

Below are several examples of Sasaki’s use of landscape chunks to communicate strategies and drive decisions for remediating landscapes and building environmental and community resiliency in response to climate change.

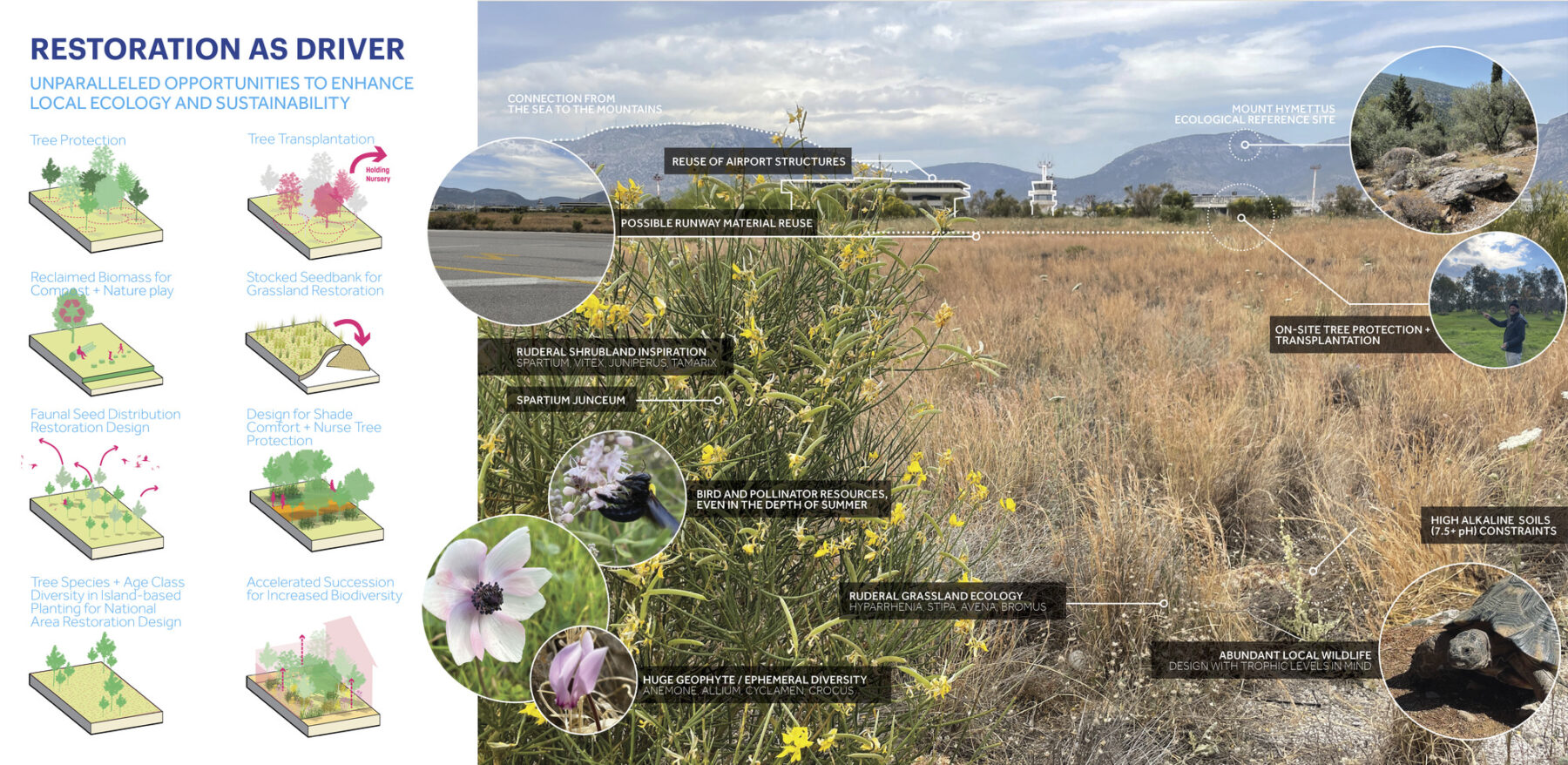

The 2001 decommissioning of Athens International Airport provides an opportunity to transform obsolete infrastructure into a restorative and resilient landscape that will become a climate adaptive park prioritizing carbon-first design. In Figure 1, Sasaki uses the chunk method to illustrate opportunities to enhance local ecology and sustainability. In addition to images of the existing site overlaid with labels indicating proposed resilient design strategies, a series of eight simple vignettes breaks down the landscape restoration plan into chunks to explain tree protection, transplantation, and succession; seed stocking and distribution; and use of trees for shade comfort, composting and nature play. The display of options uses the same axonometric frame enabling the viewer to comprehend and compare dynamic landscape systems.

Fig 1. To illustrate opportunities to enhance local ecology and sustainability on the 600-acre Ellinikon Park site in Athens, Greece, Sasaki employed landscape chunks, postage-stamp-size diagrams that break down the landscape restoration strategy, including tree protection, transplantation, and succession; seed stocking and distribution; and use of trees for shade comfort, composting and nature play. The uniform size and shape of the axonometric sections aids comprehension and comparison of dynamic landscape systems.

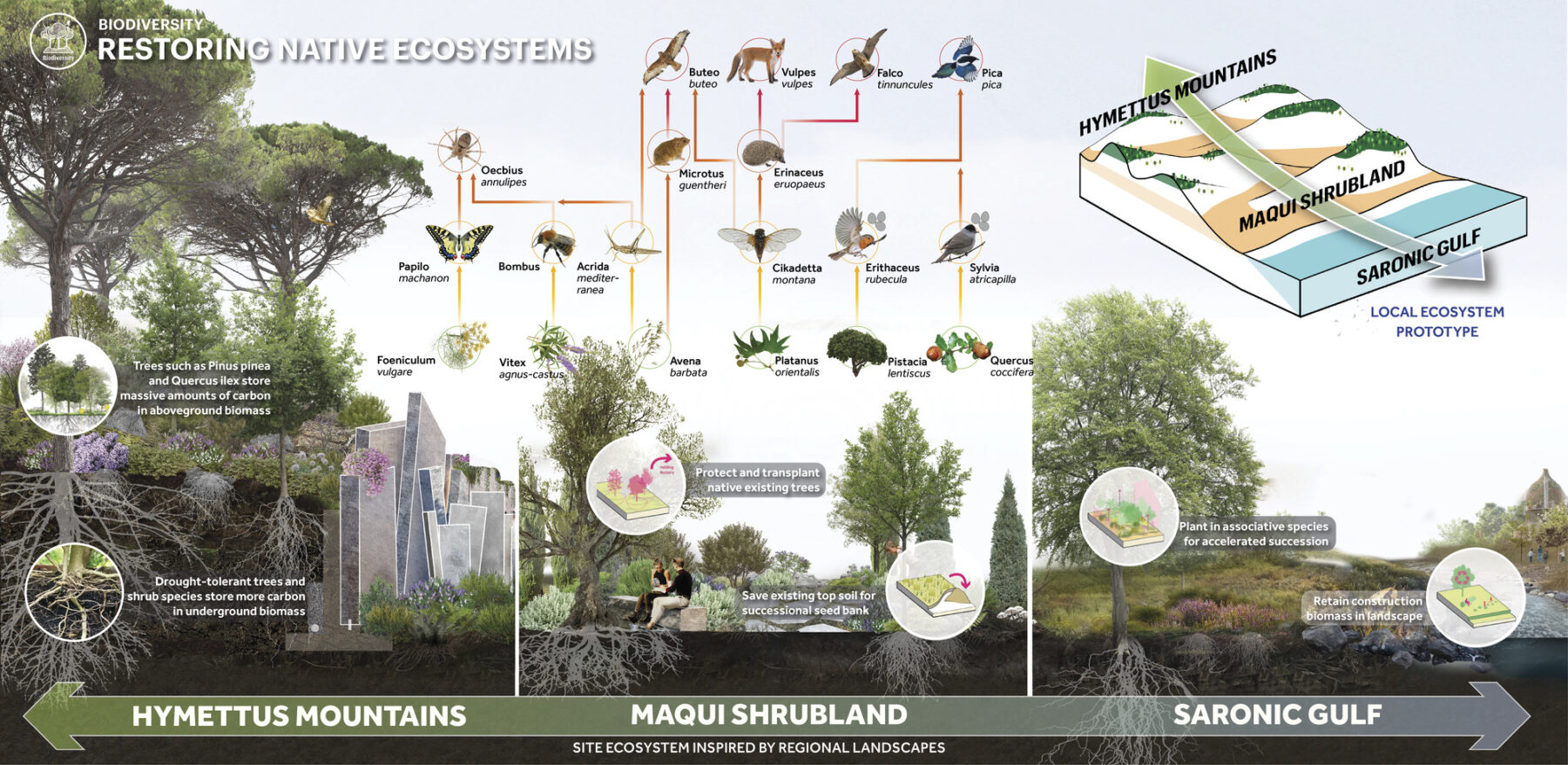

Select chunks from the Figure 1 series are then used in Figure 2 to explain how the strategies— including protecting and transplanting existing native trees, saving existing topsoil for successional seed banking, planting associative species for accelerated succession, and retaining construction biomass in the landscape—are aligned with native ecosystem prototypes which are illustratively rendered.

Fig 2. Over 3.3 million locally sourced plants were selected for their habitat value, ecosystem services, and adaptability to the site’s alkaline soils. Small landscape chunks in white circles are three-dimensional abstractions of the native ecosystem restoration goals that are overlaid on more photorealistic landscape renderings. A single chunk in the upper right corner serves as a prototype of the local ecosystem from Greece’s Hymettus Mountains to the Maqui Shrubland to the Saronic Gulf.

v Edward R. Tufte, Envisioning Information (Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press, 1990), 12.

vi Tufte, Envisioning Information, 12.

vii Tufte, Envisioning Information, 67.

viii Tufte, Envisioning Information, 68.

How do Sasaki’s ecologists use their blend of landscape architecture and ecology schooling and expertise to influence design decision-making?

Sasaki’s Allyson Mendenhall moderates roundtable discussion on fostering gender equity in landscape architecture