Aeshna Prasad: Connecting Ecology, Policy, and Place

Sasaki

Sasaki

Driven by a deep interest in the overlapping systems of cities, urban designer Aeshna Prasad has worked on large-scale projects across India, the Middle East, and the United States. Growing up in Mumbai, Aeshna learned first hand how the built environment influences how people live.

As an urban designer, Aeshna is drawn to the complexity of urban life and the challenges of long-term planning. Her approach—shaped through work across regions, sectors, and scales—is grounded in context and attuned to both the goals of the client and the aspirations of the communities involved. At Sasaki, she plays an integral role on projects focused on long-range visioning efforts and those in geographically complex contexts. She does this by leveraging her interdisciplinary background, merging ecological thinking, data analysis, participatory frameworks, and design principles to help deliver innovative and inclusive solutions to complex urban challenges.

It wasn’t a straightforward route, but I’ve always been curious about how cities feel and how they shape the lives of the people within them. Growing up in Mumbai, I became attuned early on to the way infrastructure like the train system served as a lifeline, and how density, informality, and spatial inequality defined the rhythms of daily life. That curiosity led me to study architecture, but I soon realized I was less interested in individual buildings and more drawn to the systems they were part of.

Even during my undergraduate studies, I gravitated toward broader urban questions.. My thesis focused on revitalizing a historic district in Mumbai, tackling themes of heritage, urban memory, and spatial justice. After graduating, I practiced architecture in India for several years and led hospitality projects through construction. But over time, I recognized that my sphere of concern had expanded beyond the building scale. I was drawn to the scale, complexity, and long-term influence of urban design.

That realization set me on a path toward urban design. I enrolled in the Master of Urban Design program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and midway through, added a second degree in Design Studies with a specialization in Ecologies and International Development. I wanted to understand not just how to design systems, but how to implement them, how governance, land, and regulatory frameworks shape what becomes possible. That dual-degree experience has deeply informed how I think and work today.

Aerial rendering of Salalah New Smart City

The shift was significant, but deeply energizing. Early in my career in India, I worked on hospitality and public realm projects where we could move from concept to construction in just 90 to 120 days. These projects offered immediacy, creative authorship, and rapid iteration.

In contrast, the city-scale and regional plans I work on now—such as the Greater Salalah Structure Plan or the Jubail Island Master Plan—unfold over decades and involve a much more layered set of actors and systems. As urban designers and lead consultants, we’re tasked with synthesizing inputs from engineers, ecologists, policymakers, and stakeholders into integrated, actionable spatial frameworks that can be delivered on the ground.

What excites me most is the strategic complexity: designing a framework today that is resilient, adaptive, and still relevant 30 years from now. It requires constant shifts in scale, zooming out to articulate long-term visions, and zooming in to ensure feasibility at the plot or infrastructure level. That ability to think across time, systems, and detail is what makes this work both challenging and incredibly rewarding.

Aerial of the New City Salalah Master Plan, part of the Greater Salalah Structural Plan

It deeply shapes how I think about urban design, not just as a spatial discipline, but as a negotiation between systems, policy, and lived experience. My academic work focused on incremental housing and land-as-infrastructure, particularly in contexts where the state plays a central role in shaping access to space. That foundation continues to inform the way I approach projects today.

For the Greater Salalah Structure Plan, for instance, I drew from India’s Gujarat Town Planning Scheme to propose land pooling strategies suited to Oman’s development framework. Across different geographies, I’ve found that land is framed differently—sometimes as a collective resource, sometimes as a commodity. My role is often to bridge that gap: to position equity and ecological resilience not as trade-offs, but as part of the value proposition.

On campus projects like the Utah Tech University Innovation District, we’ve had the freedom to experiment because of unified land ownership. In contrast, developer-led projects require a more metric-driven approach. In both cases, I use my background in land policy to shape frameworks that are grounded, adaptable, and implementation-ready. It’s about translating big-picture values into strategies that work on the ground.

Rendering for Utah Tech Master Plan

Two come to mind. The first is the Jubail Island Master Plan in Abu Dhabi. It was my first project at Sasaki and brought together many of my core interests. The site sits within the only mangrove national park in the region, and we proposed a carbon-neutral, mixed-use development that placed the mangrove ecosystem at the heart of the plan. It was a bold vision, but we gained client buy-in by framing ecological preservation as a strategy for wellness, identity, and long-term value.

I contributed across the full arc of the project—from early narrative framing and ecological overlays to development phasing, land use metrics, and implementation strategy. One of the most exciting aspects was envisioning new forms of amphibious living, where water-based mobility and everyday life are fully integrated.

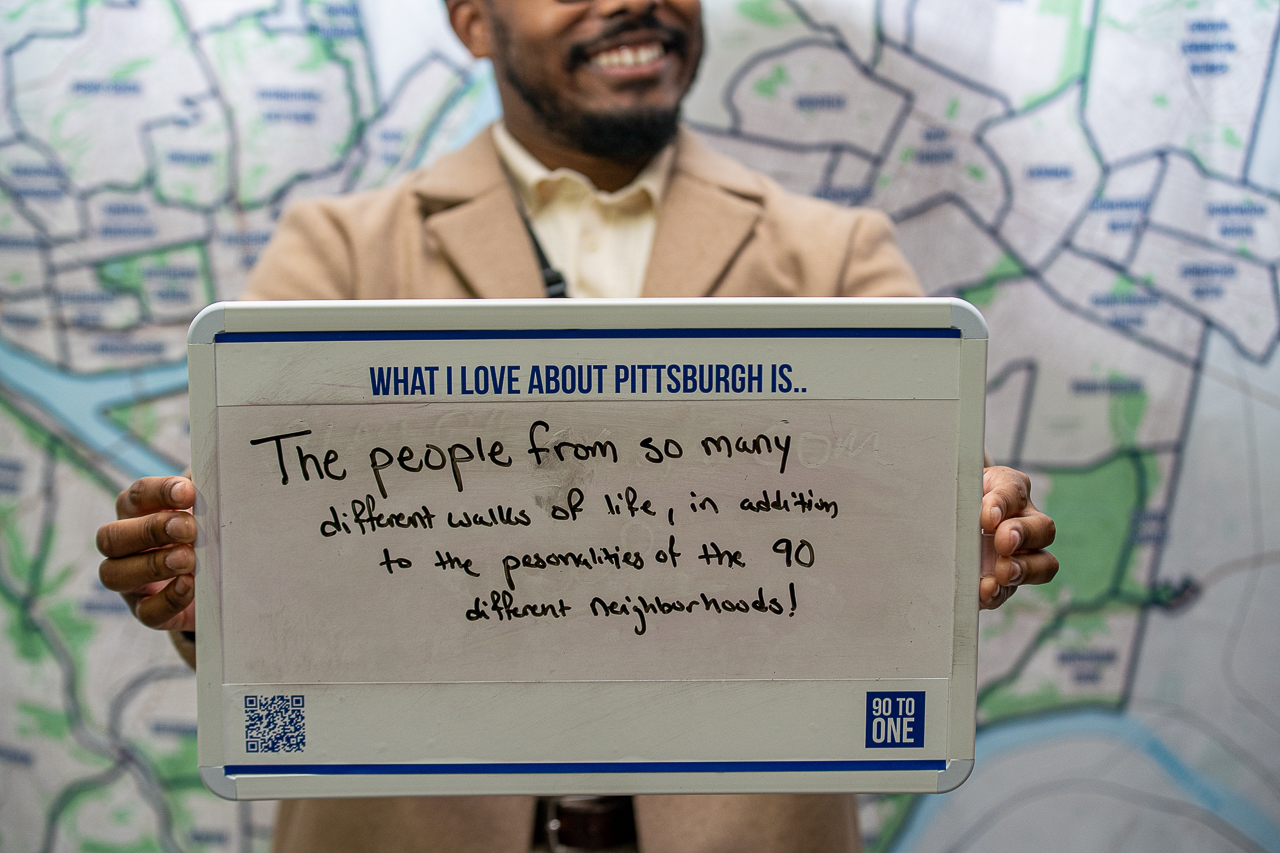

At the other end of the spectrum is the Pittsburgh 2050 Comprehensive Plan, rooted in public participation and civic engagement. I led the design of the visual identity for the “90 to 1” exhibition, which highlighted stories from each of Pittsburgh’s 90 neighborhoods. I created a suite of interactive tools, including large-format maps, color-in worksheets for children, and street-level photo installations that brought local voices into the citywide visioning process.

Aeshna worked on the 90 to One campaign for the Pittsburgh Comprehensive Plan, which gathered community input on the project.

Seeing children place pins on maps and adults leave reflections in booths and sketch notes at the public launch was deeply fulfilling. Having spent years on projects with long implementation timelines, this one felt immediate and personal. It reminded me that urban design is as much about enabling civic authorship as it is about shaping physical form.

Aeshna and colleagues in work sessions.

I think of myself as a specialized generalist, someone who connects ideas across scales, disciplines, and systems. My role often begins with driving the urban design conceptualization: developing the narrative, establishing the spatial framework, and articulating the core principles that guide a project from vision to implementation. But I also carry that thinking forward—translating big ideas into spatial strategies, design moves, and development logic.

What I enjoy most is acting as a bridge between consultants, between disciplines, and between vision and execution. That might mean integrating ecological overlays into land use frameworks, aligning demographic data with phasing plans, or shaping the way we communicate the work to civic or ministerial leadership. I’ve contributed to everything from co-authoring planning guidelines to shaping internal workflow, managing teams, and making presentations to leadership.

What makes this work especially meaningful is the ability to bring coherence to complexity. Across the many geographies I’ve worked in, from Oman to the U.S., I’ve learned that the most impactful contributions often come from synthesizing disparate voices into a shared design language, one that’s grounded, actionable, and future-ready.

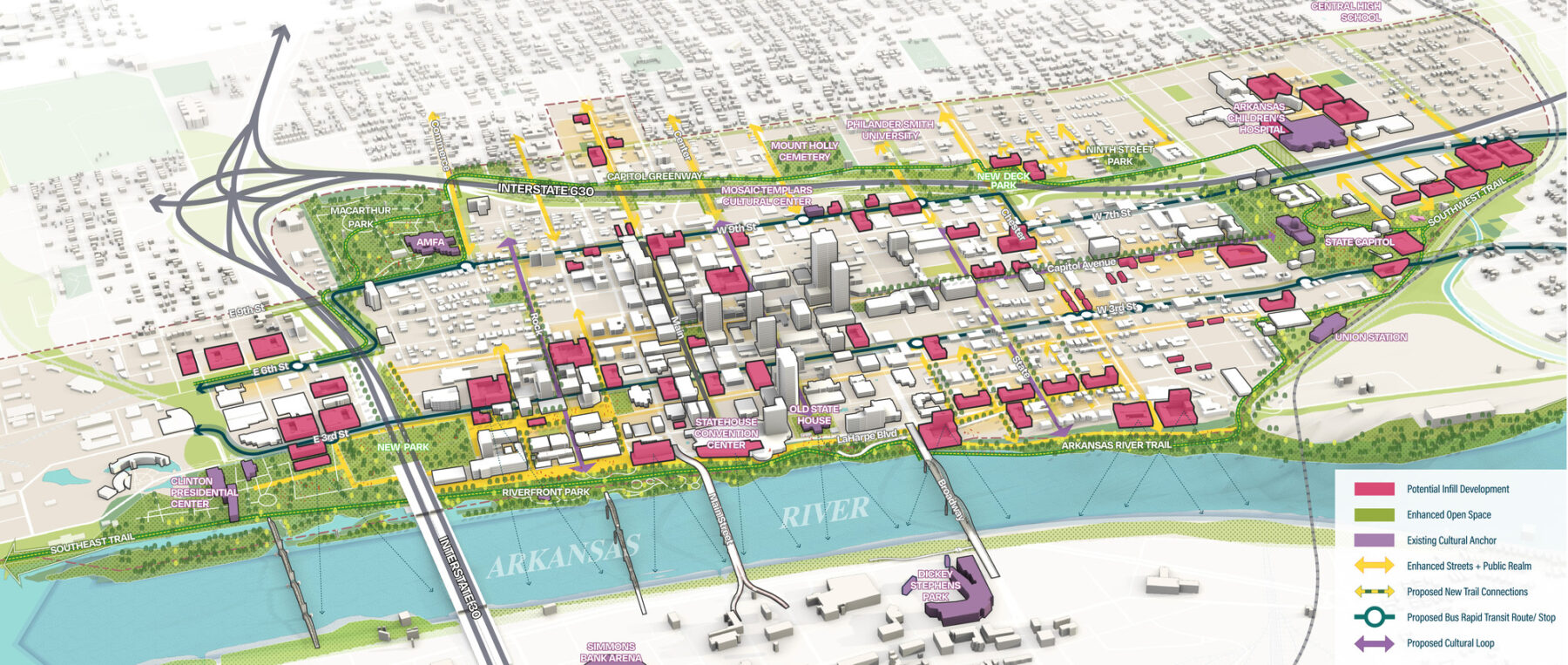

City of Little Rock Downtown Master Plan

While geography matters, I’ve found that the biggest influence is the client structure since each comes with different priorities and constraints. In government-led projects—like Greater Salalah or Downtown Little Rock—policy and public engagement play a central role. In campus plans, a single landowner means more room for experimentation. In developer-driven projects, the challenge is aligning design values with return-on-investment goals. No matter the context, I try to hold onto core principles: ecological resilience, social inclusion, and long-term adaptability. I adjust the narrative to speak to what clients care about.

Absolutely. There’s a growing recognition that cities must be designed not just for today, but for long-term ecological and social resilience. More and more, urban designers are moving away from fixed, prescriptive solutions and toward adaptable frameworks, tools and guidelines that can respond to uncertainty, shifting priorities, and evolving conditions on the ground.

There’s also a deeper acknowledgment of the informal, the incremental, and the participatory. The notion that there is no singular expert, but that the most powerful insights often come from those who listen, is becoming more central to how we practice. It’s a shift from authorship to co-authorship, and from control to care.

Globally, climate adaptation and nature-based infrastructure are no longer peripheral, they’re becoming core to how we think about urban systems. What excites me most is that these conversations are no longer niche, they’re shaping the mainstream, and pushing the field toward more integrated, more human, and more resilient ways of shaping cities.

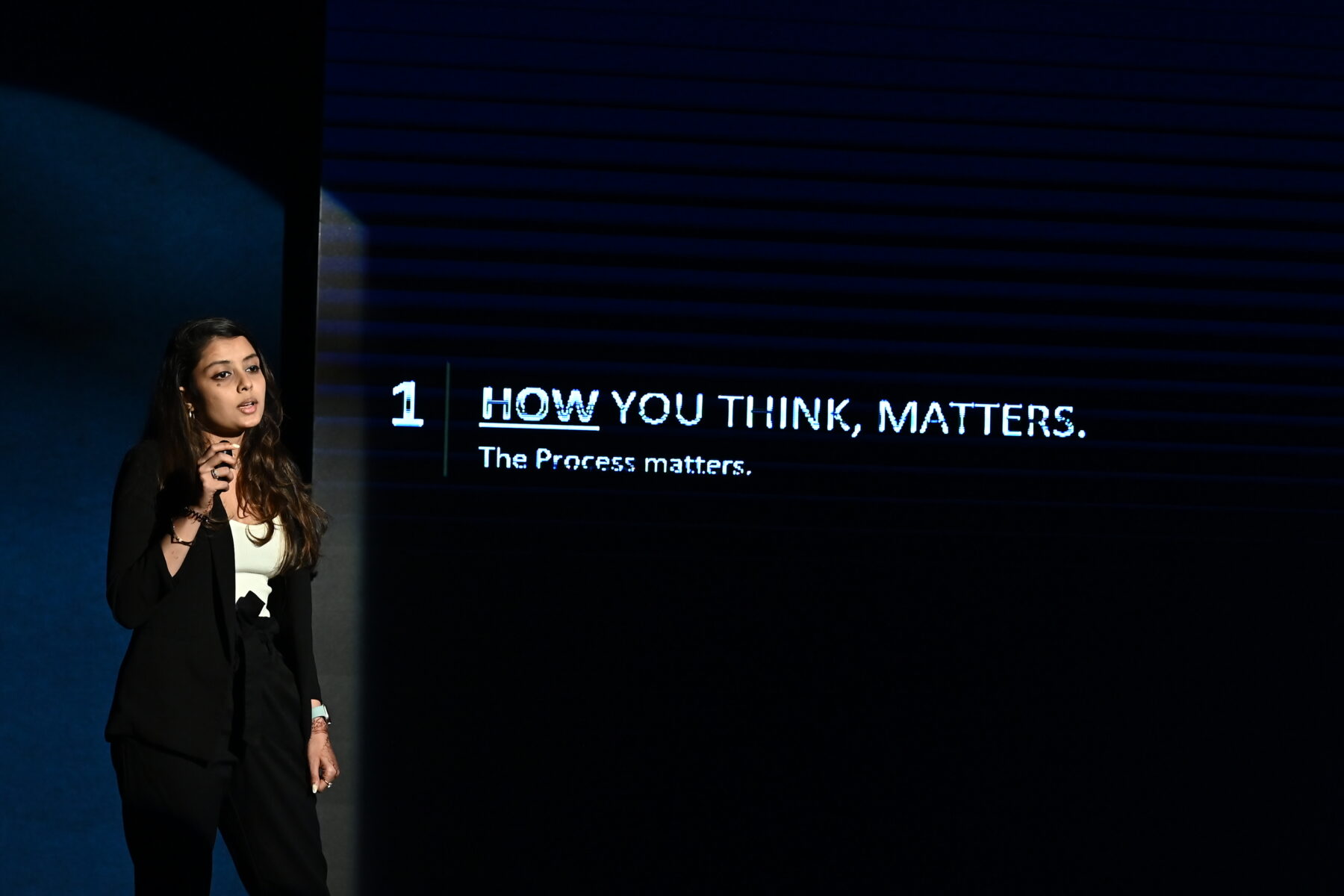

Aeshna Prasad presents at TEDxYouth at BVBRaipur.

I actually gave a TEDx talk a few years ago titled “10 Things I Learned as a Designer I Wish Everybody Knew,” and I still stand by all of them.

But to highlight a few: Stay curious. Try different scales, project types, and geographies. That’s how you discover what you care most about. Take risks, ask questions, and listen deeply. Cities are shaped as much by people as they are by plans, and if you listen well, you can design in ways that reflect that complexity and beauty. And most importantly, hold onto the idealism that led you here. Believe in the hope and optimism of design. That’s what keeps you going through the messy, beautiful process of shaping cities.