2018 Research Grant Winners Announced

Sasaki

Sasaki

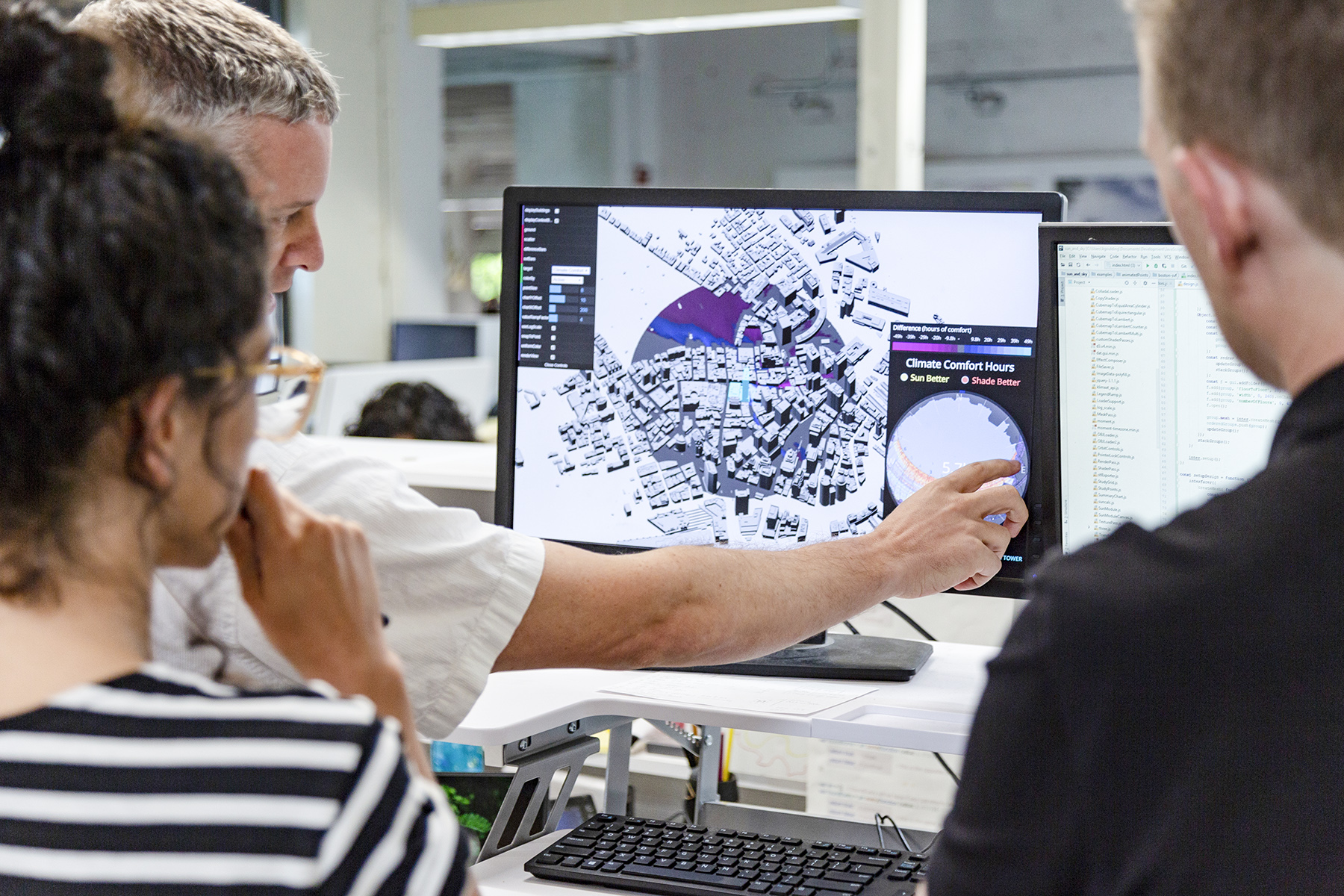

We believe that focused research is a critical vehicle for creative innovation and honing our collective problem-solving skills. Now entering its fourth year, Sasaki’s annual internal research initiative encourages the firm’s most passionate and enterprising professionals to delve into research that informs project work, the firm’s capacity to serve clients, and the future of the industry at large.

Previous grant winners have explored best practices for incorporating autonomous vehicles into the built environment, used data visualization to gain a better understanding of the United States’ homeless population, and conducted post-occupancy research on the value of varied playscapes in landscape architecture.

Sasaki’s internal research runs parallel to the Sasaki Foundation’s grant program, which announced its inaugural cohort in October. Through these efforts, we are advancing industry knowledge and promoting an interdisciplinary approach to tackling challenges.

This year’s call for proposals garnered eight responses, with three projects being selected by a team of judges. Read the abstracts for this year’s selected research projects below:

Team: Melissa Isidor, Elaine Limmer, Briana Outlaw, Nayeli Rodriguez

A Voice at the Table will explore the role that “third spaces” play in promoting community building, empowerment, and resilience for black women in their communities. Using Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood as a case study, the project will investigate the social and economic value third spaces provide to the neighborhood and the City of Boston. At large, the project will examine how planning and design can better serve the present and future needs of diverse communities.

So, what is a third space? The term third places was first coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg and refers to places where people spend time between home (‘first’ place) and work (‘second’ place). Third spaces can take many forms—but are defined as places where people feel a strong sense of self, identity, community, and belonging.

Team: Victoria Fisher, Gretchen Keillor, Patrick Murray

“Flyover Country” is not a particularly flattering moniker. Even less so when it accounts for one-fifth of a nation’s population; yet this phrase reflects the assumptions coastal urbanites often project upon their Midwestern fellow citizens. There is a gap in understanding between those who live on the coasts and those who live in middle America, and between those who live in cities and those who live in small town and rural areas.

As designers and planners who create places for people, it is imperative that we not forget these populations: those who live in middle America, and those who live well outside of the hustle and bustle of urban life. This research seeks to answer three main questions: What are the current trends in small town Midwest America? How can small towns of the Midwest be characterized into typologies? And what are the trends and key drivers that will impact the future of small town America?

The summation of this research effort would speak to the gap in understanding of these places by providing a more nuanced portrayal of what small town America, specifically in the Midwest, looks like.

Team: Jill Allen Dixon, AICP; Laura Marett, ASLA, PLA, LEED AP

Parks are an essential part of a city’s social life, supporting health and wellness for communities across our country. Access to high-quality parks with diverse amenities and programs is particularly critical for communities in urbanized areas with backyard deficits. Ensuring equitable access to great parks for all communities, especially those that are majority people of color or low income, is increasingly the focus of the cities we work with and the projects we pursue in our civic parks and resilience practices at Sasaki.

In park system planning, the traditional measure of equitable access to parks has been the 10-minute walk circle or isochrone, determining what percentage of residents live within a short walk of a park. However, these metrics do not capture inequities in parks access for different demographic groups, nor do they consider the quality of parks that communities have access to.

We believe that Sasaki can be a thought leaders in establishing a more meaningful discussion and visualization of equity in parks access by exploring the following questions: Across urbanized areas in our country, who are the communities being served by parks and who is left out? And how can we visualize inequities in park quality for different demographic groups, especially for communities of color and low-income communities?