Grove and Zhang on Design, Ecology, Resiliency, and Research

While ecology and resilience are among the most salient topics in contemporary landscape architecture, their inherent relationship and differences have deep implications on practice

Sasaki

Sasaki

The following piece was written by former senior associate Anthony Fettes and originally appeared on The Field, the blog of the American Society of Landscape Architects’ (ASLA) Professional Practice Network.

Around the world, an estimated 80 percent of all flowering plant species and over one-third of our food is dependent upon or benefited by animal pollinators. However, many of these pollinator species are in decline, threatening the productivity of both global food production and ecological communities. What is causing this decline? How are we contributing, and what can be done to reverse this trend?

With reports of dramatic bee kills from acute exposure to neonicotinoids, the wide-spread prevalence of pesticides is frequently implicated in the decline of bees, butterflies, and other beneficial insects. But upon further inquiry, pesticides are only one component of more complex and interrelated challenges facing pollinators. Loss of habitat for feeding, nesting, and overwintering is often equally, if not more, detrimental than pesticides alone. Fragmented foraging sites require many pollinators to travel further distances in search of resources, thus increasing their exposure to pesticides, pollution, and extreme weather events. Together, the compounding effects of habitat loss and climate variability can reduce the seasonal reliability and abundance of floral resources—impacting nutrition and reproductive success, leaving pollinators stressed, and making declining populations more susceptible to disease, parasites, and poisoning.

Diverse pollinators are essential to successful food production

As landscape architects, one of the most effective ways we can improve the ecological benefit of any landscape is knowing how to identify, enhance, and create habitat for pollinators. But before maxing out a planting design with an abundant array of colorful blooms and anticipating the buzz of activity, there is more to consider than simply specifying a preselected pollinator seed mix or plugs. So, what exactly is pollinator habitat? For many, an open wildflower meadow or garden with the familiar stacked box (Langstroth) style beehive may be the first thing that comes to mind. However, pollinator habitat includes a diversity of floral resources for foraging, safe locations, and materials shelter/nesting sites (or host plants for butterflies and moths—Lepidoptera).

In 2016, my colleague Tao Zhang and I had the opportunity to attend the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) Conference in Washington D.C. Trained as both landscape architects and ecologists, we embraced the technical nature of the conference and quickly found new ways to integrate our expanded knowledge into practice. In 2017, we were honored to lead an education session on the topic of designing pollinator habitat at the ASLA Annual meeting in Los Angeles (FRI-C02 – Bee There or Be Square: Promoting Pollinator Habitats in Landscape Architecture). Collaborating with two botany experts to whom we were introduced at the NAPPC Conference, we shared some lessons learned, presented some key points on plant selection, and offered guidance on how to better integrate pollinator habitat into landscape designs. The following summary offers some key takeaways from this education session, along with some key resources to learn more.

The Western or European honey bee (Apis mellifera) may be the most iconic insect pollinator. However, this domesticated, non-native insect often overshadows the 4,000 bee species that are native to North America. From large, fuzzy bumblebees to the tiny mason bee which may be confused with fly to the untrained eye, bees represent some of the most pervasive and efficient pollinators in the insect world. Even flies are pollinators as well, representing some of the most important insect pollinators in cold alpine and arctic regions.

Monarch caterpillar on a marsh milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) host plant along the Chicago Riverwalk (Courtesy of Anthony Fettes)

According to current estimates, there are an estimated 200,000 documented animal pollinators around the world which include: butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera), wasps, beetles, birds, bats, and some mammals. While this article primarily focuses on insect pollinators with an emphasis on native bees, having a deeper understanding of your target species will help inform the planning and design process.

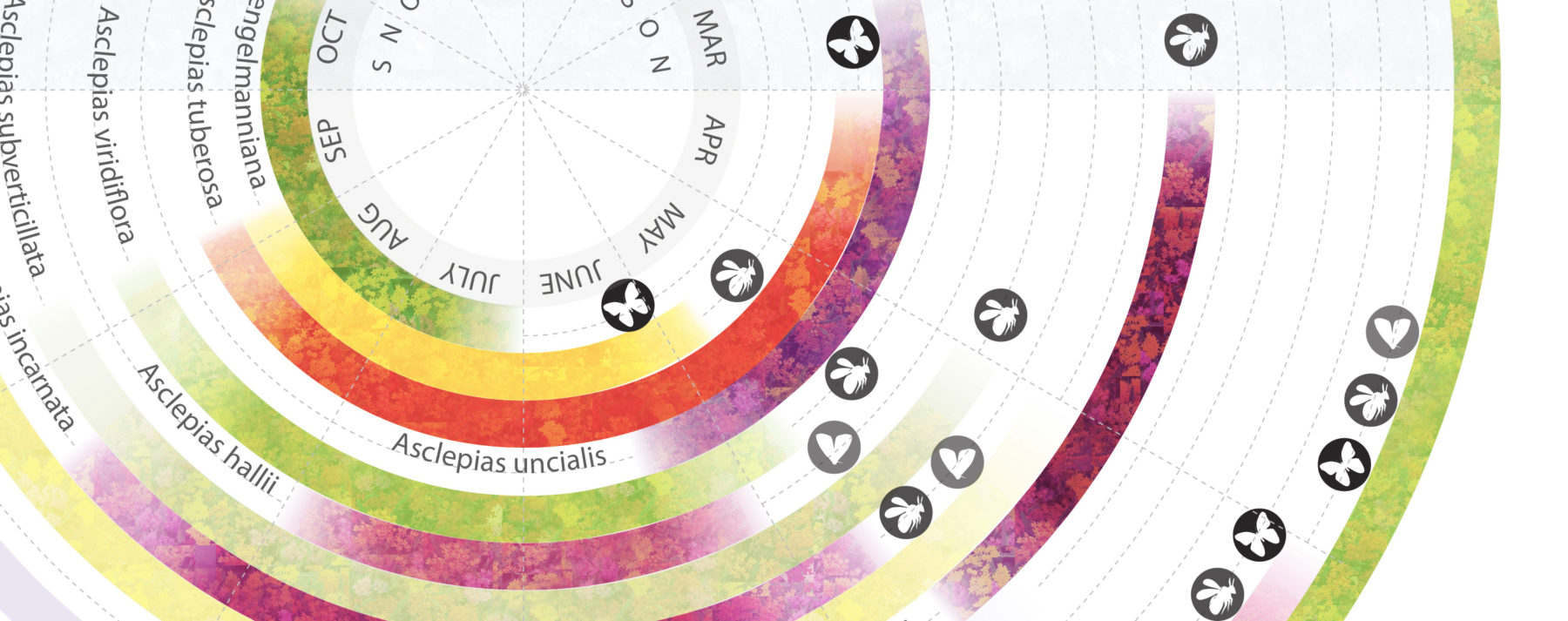

A good planting palette should always aim for full season color and blooms. While this should provide the minimum pollen and nectar resources for your local pollinators, ideal pollinator habitat should provide significant native floral diversity, optimized for your site’s conditions. In general, the more biologically diverse a site is, the more species of pollinators it can support.

To understand how diversity plays into this, we need to understand plant-pollinator interactions and the importance of providing resources for the entire season and life cycles of pollinators. However, in the general scheme of things, designing for bloom time and patch consistency is often more critical and beneficial. Patch consistency also relates to foraging distance, as larger bees travel further than smaller bees. When foraging for floral resources, they are looking for pollen (protein), nectar (carbohydrates), and occasionally resins (for hive/nest building, beeswax) depending on the current stage in their life cycle. Early season (spring) resources are the most critical for many species as they emerge from winter, however many pollinator mixes do not provide sufficient resources or diversity early in the season—with most having abundant blooms and resources in mid-late summer

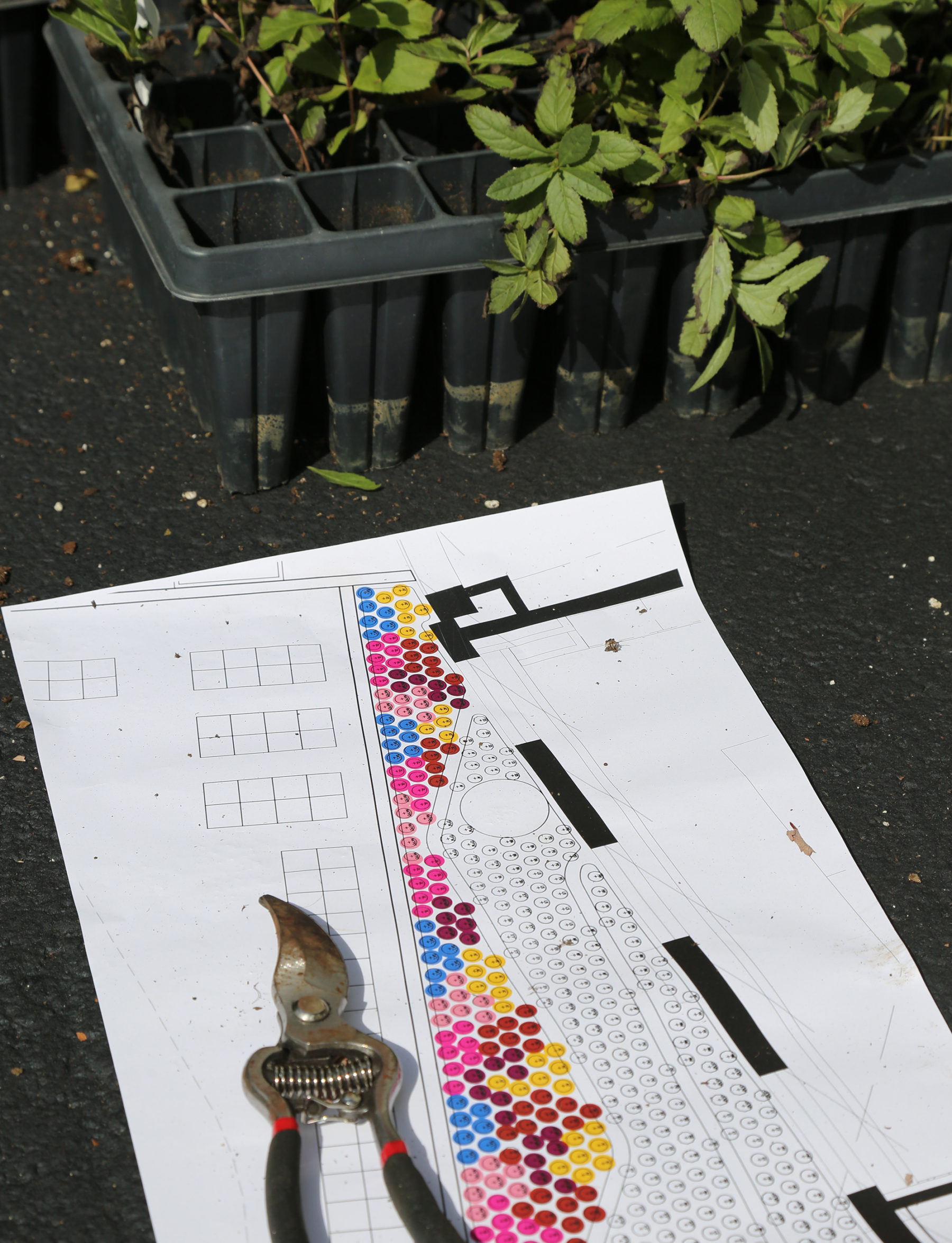

Above and Below: Planning, layout, and installation of the pollinator garden at Sasaki

A few key things to keep in mind when building your plant palette:

When it comes to building your plant palette there are a great number of resources available to inform selection and validate the benefits to pollinators. Organizations like Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, Xerces Society, and Pollinator Partnership all offer excellent resources on beneficial native plants, and are backed by research.

Foraging habits of pollinators can be distilled down to two categories: generalist vs. specialist. Species who are opportunistic and non-specific when foraging, like honeybees and some species of bumble bees, are considered generalists and often quite abundant. On the other hand, specialist pollinators have specific beneficial relationships or mutualisms with a particular flower type or attraction to specific sources of pollen or nectar. Yucca moths (Tegeticula sp.) are one example where plant (Yucca spp.) and pollinator are mutually dependent on each other for survival. At a broader scale, plant-pollinator mutualisms influence plant reproductive success of specific species, affecting genetic diversity and quantity of seeds produced, ultimately impacting the success of ecological communities and ecosystem services beyond pollination.

There are numerous examples of specific plant-pollinator relationships where native wildflowers, trees, and shrubs support some of the rarer species of bees and butterflies. This is why local adaptation is important—where a wide range native species will support a diversity of adaptations from generalist to specialist. In a general sense, these relationships are manifested in pollinator syndromes. While pollinator syndromes are often observed in nature, they are not definitive and should only serve as a general, albeit interesting, guide.

After feeding on nectar and collecting pollen, bees return to their hives and nests for shelter, to raise their young, and to overwinter. While it is noted that 75% of bees typically forage within 0.6 miles (1 km) of their nests, smaller species like the mason bee (Osmia spp.) can only travel a few hundred yards—benefiting greatly from integrating nesting sites.

Unlike the large, comb-filled hives of the European honey bee and other social bees, about 70% of native bees are solitary and nest in the ground. The remaining 30% nest in wood cavities and hollow stems. In an undisturbed or unkempt landscape, these spaces and resources are often abundantly available, only to be cleared out to “improve” or develop a site. While some level of disturbance is inevitable, be sure to recognize existing nesting habitat or resources and incorporate those existing materials and ideal conditions where feasible. This is ultimately a matter of selecting the right plants to provide hollow or pithy stems and adjusting routine maintenance practices to not remove or smother nests. One emerging trend it to also create bee houses, presenting design opportunities to create tunnel nests and nesting blocks to incorporate into your designed pollinator habitat.

For butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera), plant selection and careful maintenance are critical. For the early life-cycle of Lepidopteran species, all begin their life as eggs laid on or near a specific host plant. For the young larva (caterpillar) and pupa (chrysalis) stage of these insects, the host plants provide the resources they need for early development to complete their life cycle. The most recognizable host plant association is that of the Monarch butterfly and the genus Asclepias or milkweed. However, not all host plants are herbaceous wildflowers. It is important to consider that many native trees, grasses, and vines may also be host plants. There are several resources like wildflower.org and the Natural History Museum in London that have excellent national and global resources to help identify and select Lepidopteran hostplants.

Regardless of how much effort goes into planning your pollinator habitat, everything can all fall apart during maintenance. Routine practices like early dead-heading can rob pollinators of foraging resources, end of season clean up can remove critical nesting habitat and chrysalides, and excessive mulching can discourage ground-nesting bees from taking up residence. While it may not be feasible in every landscape, aim for leaving a percentage of your pollinator planting (2/3 for larger restoration sites) undisturbed annually. Common yard waste such as leaf litter, downed wood, and uncut bunch grasses all have the potential to be overwintering sites.

Use of pesticides and herbicides is not recommended. Ultimately, “a plant that has fed nothing has not done its job” and with sufficient diversity, the pollinator garden should self-regulate. If additional means of control are deemed necessary, be sure to use integrated pest management techniques and/or ecologically-based maintenance practices to minimize/avoid pesticide use. This is especially critical when pollinators are foraging. But don’t forget to consider maintenance and land management practices beyond your site. While a designed pollinator landscape may provide optimal resources, foraging is likely to extend beyond one specific location, potentially leading to pesticide exposure in surrounding, traditionally maintained landscapes and agricultural areas.

While venturing beyond the typical “pollinator seed mix” and taking a more comprehensive approach to designing a pollinator habitat may seem a bit daunting, there many professional and organizations that are eager to help. While not every project can afford to consult with an ecologist or botainist, there may be opportunities to collaborate with local universities, botanical gardens, and arboreta to engage in a “BioBlitz” to gather baseline data during a projects’ site analysis phase.

Co-located pollinator and vegetable gardens, such as Sasaki’s on-site garden, provide an opportunity to learn about beneficial ecosystem services while improving productivity

Many of these same organizations may also be able to assist during design, construction, and post-occupancy evaluations as well, presenting opportunities for consultation and research. Regardless of the project scope or scale, be sure cultivate an awareness of the many citizen science initiatives that are out there. At a minimum, list your pollinator habitat on the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge, or submit observations of Monarch butterflies and bumble bees, to contribute to the growing body of pollinator research.

As landscape architects, we have an obligation to support the diversity of pollinators and ecosystem services they provide. To ensure the health and resiliency of the landscapes we all share in common we need to embrace the complexity of these landscapes and underlying systems. By expanding our knowledge of pollinators and connecting to the many resources available, we can work to address the landscape scale issues impacting pollinators around the world, from the smallest backyard garden to a large-scale restoration landscape.

A special thanks to my fellow panelists at the 2017 ASLA Annual Meeting in Los Angeles: Tao Zhang, PLA, LEED AP ND, SITES AP, Principal, Landscape Architect & Ecologist at Sasaki; Rob Fiegener, Native Seed Director at the Institute for Applied Ecology; and Pati Vitt, Senior Scientist & Manager of Conservation Programs, Stone Curator of the Dixon Tallgrass Prairie Seed Bank at the Chicago Botanic Garden. Session details: FRI-C02 – Bee There or Be Square: Promoting Pollinator Habitats in Landscape Architecture.